A new film about the 2007 Te Urewera police raids chooses creative license over historical accuracy. Is there value in going beyond the facts when we’re retelling stories from the past?

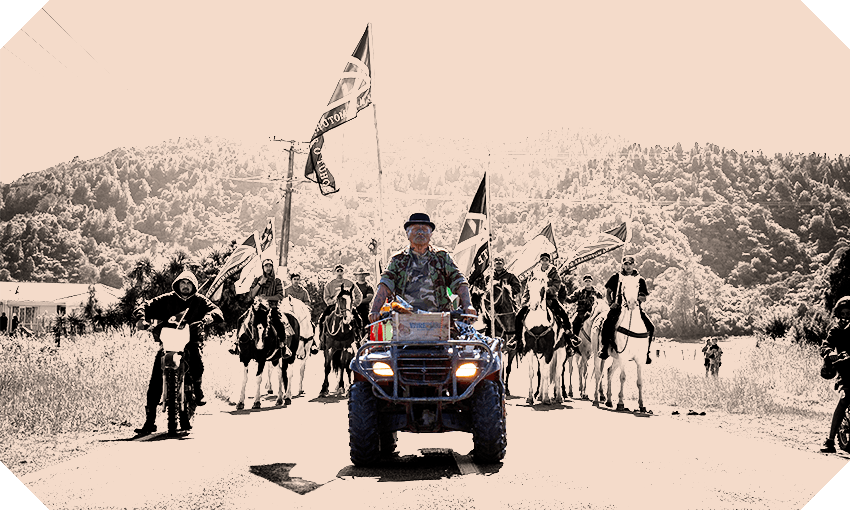

The events that unfolded on 15 October 2007 have had a lasting impact on Ngāi Tūhoe. On that day, a helicopter and convoys of marked and unmarked police vehicles descended upon the small valley town of Rūātoki in the Bay of Plenty. Set against the backdrop of dense Tūhoe native bush, the town was blocked off and cars, houses and school buses were searched by heavily-armed police who were hunting for people they believed were involved in military-style training camps in Te Urewera Ranges.

Muru, a new film by director Tearepa Kahi being released this week, is described as “a New Zealand action-drama film about the 2007 New Zealand police raids of the Ngāi Tūhoe community of Rūātoki”.

The film opens with evocative shots of the abounding valleys cloaked by the mist of Hinepūkohurangi. As the film takes shape, it’s clear that there is dedication to what happened on that day 15 years ago, when the raids took place. It’s filmed on location with kaumātua and tamariki from the community speaking in Tūhoe dialect. Tame Iti plays himself and particular events from the day are replicated in meticulous detail.

But despite centring on a day of actual events, Muru revolves around mostly fictionalised characters. Among the unsettling violence, people are shot, pushed from helicopters and some are killed (no one was killed during the raids in 2007).

The film makes it clear early on that a different creative direction will be taken. In the first minutes, a declaration is typed out on screen: “This film is not a recreation… it is a response.”

It’s often suggested that New Zealanders know very little of our local, collective history. Until very recently, we were one of very few countries in the world to not ensure citizens have some experience of their own past as part of their education.

Within that context, one can imagine how historical-based films like Muru – and others like Whina, the biopic on Māori leader and activist Whina Cooper, or television miniseries Panthers that focused on the 1970s dawn raids and emergence of the Pacific Panthers – are useful for forging wider cultural awareness of our past. But, knowing how little we know, how should we treat texts that divert from accuracy?

“History has fascinated filmmakers right from the beginnings of cinema,” says Giacomo Lichtner, an associate professor in history and film at Victoria University of Wellington. He explains the reason for that fascination is twofold. The first is narrative: history is filled with compelling material, stories and conflict to make films. The second is cultural and commercial: audiences continue to want to see history on screen, “because we always look to history to define who we are”.

That fascination is familiar when you look back through the history of New Zealand cinema too. The 1922 film Birth of New Zealand depicted key events in New Zealand history; the 1925 double feature Rewi’s Last Stand is based on the last stand of Rewi Maniapoto at the Battle of Ōrākau; Merata Mita’s 1980 documentary Bastion Point: Day 507 followed the government eviction of Ngāti Whātua from their land; and the 1983 “Māori western” Utu is inspired by events from Te Kooti’s War. Our interest in seeing histories, both recent and distant, persists.

In the early development stages of Muru, the vision for the film adhered to a more familiar form of historical storytelling. With a background in history and documentary filmmaking, Kahi describes his initial concept as being “very traditional and very faithful” when it came to the history of the raids. When Kahi and Tame Iti met with the Kōmiti o Runa o Ruātoki to seek its endorsement for the initial meticulously-researched vision for the project, they were met with requests that the depiction not simply be about the events of a single day. Tūhoe had been subjected to hundreds of years of government grievances, the reasoning went, including multiple raids by the government and that the one day was bound up in a far more complex historical context.

“I thought, I’ve got to listen, I’m going to go back to the whiteboard and I just started wheelbarrowing in more and more threads,” says Kahi. In the end, with the guidance of Iti and the community, the film morphed into a response to hundreds of years of history, including but not limited to the 2007 raids, the 1916 government raids to arrest Rua Kenana – in which Kenana’s son Toko and uncle Te Maipi were killed – and the 2000 police killing of Waitaha 23-year-old Steven Wallace.

To Kahi, having a strong foundation in understanding of what happened on the day of the raids through research, interviews and relationships was vital in telling that bigger story. “Having done all the interviews, it would have been such a missed opportunity to not go deeper and tell a much more thematically authentic story,” he says.

In a 1992 essay on documentary filmmaking, Ngāti Apa filmmaker Barry Barclay wrote: “For myself, I trust the letter writer to hunt out the metaphor that counts, rather than a person blinkered to reportage.” By that, he meant documenting stories through filmmaking should go beyond just facts, balance and accuracy – that a more valuable and lasting representation would find ways to encapsulate thoughts, emotions and vastness on the screen.

There’s a tendency for commentary surrounding historical-based cinema to focus on accuracy and whether events shown on screen really happened in the way they’re represented. Lichtner says that while it’s important filmmakers are honest about invention to their audiences, judging films only on their supposed accuracy is likely far too narrow a lens. “A film can be inaccurate in terms of what it represents, but accurate in terms of the meaning of history that it conveys, just as it can convey true events through invention and imagination” he says. Art has the tools to give colour to ephemeral data, like what people feel or how people think – the type of data that traditionally, academic framing of history has struggled with.

“There are different ways of approaching history,” says Matariki Williams (Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Whakaue, Ngāti Hauiti, Taranaki) Pou Matua Mātauranga Māori at Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture and Heritage. The way that Muru has evolved into a response, “takes away some of the burden of having to prove to people that this is the correct, the one and only truth, because I don’t believe that truth is absolute anyway,” she says.

Regardless of who is producing history, “it’s always going to be challenged, because it can’t be everybody’s perspectives all at once,” she adds. A single event like the 2007 raids can be experienced “so differently for different people”.

Kahi does fear the film may give others a perceived license to take liberties with history without doing the necessary groundwork of research and community involvement. “There was a lot of consultation and a lot of pou that we had in place that allowed us to tell the story in this way,” he says.

With its drummed up action and fictional characters, Muru is a new direction in historical storytelling. At the same time, Kahi believes the narratives fit old techniques of storytelling passed down from our tūpuna. “The worst thing you can do is stand up on the paepae and say what you learned by rote or repeat everything that you were told,” Kahi says. “You’ve got to be able to put your own spin on it because the worst thing you can do is regurgitate, so we avoided that.”

For Williams, there’s a power in putting the stories of history in the hand of creatives. “When someone is performing or speaking or singing to you, you feel it as well, it’s not just history, as absorbed without the human interface. That human interface makes it that next level of compelling and absorbing.”

History is of course more than just facts, it’s embedded in people, in landscapes. And it’s vital that those stories are interpreted by those within communities and those most affected by events. “It’s really important to acknowledge that history isn’t owned by people who have the job title historian,” says Williams. “History is everywhere. It’s with our elders. It’s with the people on the paepae. It’s with our kaikaranga. It’s in our buildings. It’s in our taonga. it’s in our art forms. History is everywhere.”

Muru is screening in cinemas nationwide from tomorrow.

Follow our te ao Māori podcast Nē? on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.