Te Ohu Kaimoana chief executive Dion Tuuta gets to the heart of institutional racism, and adds his voice to the chorus calling for a better Treaty partnership as we emerge from the pandemic.

Koi Tū – the Centre for Informed Futures, led by Sir Peter Gluckman, recently released a paper titled Social Cohesion Enhancing Kotahitanga in a Post-Covid World. The report suggests that as we transition towards post-Covid life, it’s critical that New Zealand considers what factors influence the nature and degree of social cohesion – and how to enhance social cohesion as we reset so that Aotearoa improves its sense of belonging, participation and legitimacy.

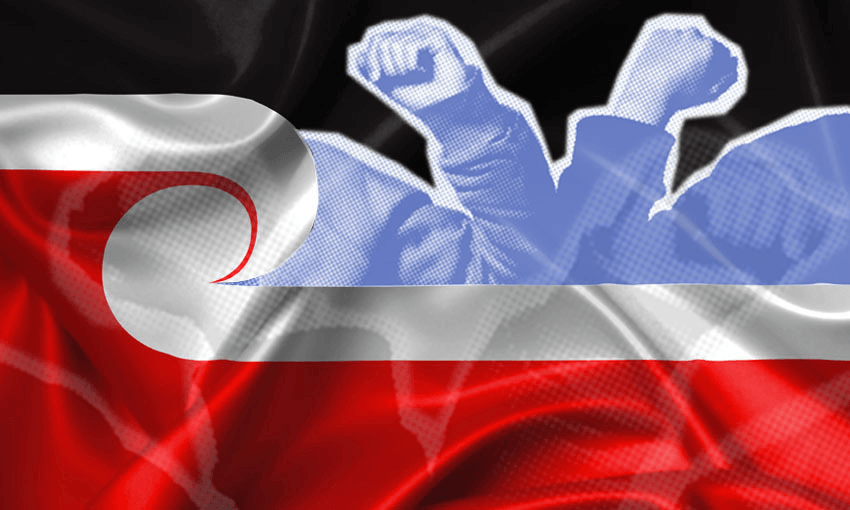

Māori have been asking government these same questions since 1840. We are increasingly asking as Aotearoa looks to a post-Covid economic and social rebuild.

Resources are being marshalled at an unprecedented scale and pace to address the economic crisis the pandemic has caused. Industry and sector leaders across Aotearoa are volunteering their ideas for how our economy can be reshaped, and government is listening with its cheque book at the ready for those who can capture their imagination. The successful stand to gain significant advantage through state support of their initiatives.

Māori leadership are keen to see how the rebuild can contribute to improved long-term outcomes for Māori whānau.

The allocation of state assistance for the rebuild will be critical and it is yet to be seen how this will play out in practice and whether Māori expectations for a meaningful relationship reset with the Crown will be met.

Without consideration of issues such as those outlined in the Koi Tū report – which identifies the importance of Māori leadership – government responses risk excluding Māori from opportunity and further entrenching inequality. Ironically, former minister of finance Sir Roger Douglas, architect of an economy that hit waged workers and the poor hardest, has stressed this general point by advocating for the government to use the pandemic response to attack economic privilege and reduce inequality – albeit without any specific focus on Māori.

The Māori experience of being overlooked by government decision-makers in favour of mainstream approaches has played out during the lockdown in a number of ways, with Māori leadership battling with limited success to get a voice at the decision-making table or even having their views taken into account.

Recently Māori health experts and industry leaders noted how they have been largely excluded from parliament’s Epidemic Response Committee meetings, leaving many feeling extremely frustrated. Some iwi leaders, such as Ngāti Kahungunu chair Ngahiwi Tomoana, have noted that iwi are ready to help but the government is not listening.

And the frustration – anticipated in the Koi Tū report – is getting louder, as exemplified by the New Zealand Māori Council’s stinging criticism of the ERC for the way it has failed to address Māori representation in its work.

From a historic perspective the state’s approach is not that surprising. It is simply demonstrating status quo behaviour from an institution and people who do not have meaningful connectivity to Māori society and Māori communities.

The government’s preferred modus operandi is to apply centrally developed solutions to Māori issues in a top down manner rather than working with iwi Māori in a Treaty-based bottom up approach. That is the story of Māori-Crown relations. And this is what Māori leaders hope that the post-Covid-19 world will change – working with us rather than being dealt to. Partnership instead of paternalism.

In the past the Crown has claimed the excuse of not knowing who represented iwi communities, but it can no longer claim ignorance. The Treaty settlement process of the past 30 years has established key infrastructure representing the iwi Treaty partner in the form of post-settlement governance entities.

These tribal entities, alongside the Whānau Ora Commissioning Agencies, have helped coordinate the bulk of the Māori response to Covid on the ground – one of the largest Māori collective responses to a crisis since the Māori war effort of WWII. It is these entities, and their valuable experience which some decision-makers now appear to be ignoring.

The government will claim that it has been working with the Iwi Chairs Forum to respond to Covid-19, but what it is really doing is using this collective as a means of communicating its decisions. Yes there was a need for the government to take swift action so New Zealanders did not needlessly suffer the consequences of the economic breakdown. But as we move out of the state of emergency we currently face, the nature of how Aotearoa makes decisions in a post-Covid – Post Treaty settlement (but not post-Treaty) world will demand examination. Involvement in, and ownership of the decision-making process contributes to the quality and durability of the outcome. And the durable outcome that Māori have always sought is a fairer Aotearoa.

It seems to be a part of human nature to naturally default to the things and people you know and are familiar with. But if you always talk to the same people – as some of our decision makers and political gate keepers seem to be doing – you will generally get the same outcome. Perhaps this is the essence of institutional racism which has been so detrimental to Māori.

Whatever government’s decision-makers choose to do, our rebuild will require Aotearoa to demonstrate greater resilience and self-reliance – the sort of resilience and self-reliance that iwi Māori are demonstrating at the local level.

Māori will emerge from this stronger and more connected because of our focus on protecting people. It will be difficult and there will be trying times ahead. But the commitment and leadership our iwi and Whānau Ora commissioning agencies are demonstrating on the ground has shown the strength of Māori resilience through kotahitanga (unity) and whanaungatanga (relationships).

I would urge those in power to engage with their Treaty partner and learn from their experience. You never know – you just might learn something.