Morgan Godfery was born to a teenage mother and a gang father in Kawerau, New Zealand’s poorest town. He recounts the experience in this essay from the Journal of Urgent Writing, 2017.

Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future

And time future contained in time past.

— T. S. Eliot, ‘The Four Quartets’

Home

Kawerau, an old industrial centre about 45 minutes east of Rotorua, is a faded border town where the dusty Rangitaiki Plains meet the pumiced edge of the Central North Island’s volcanic plateau. The easiest route to town, turning east at Rotorua via State Highway 30, takes you through spectacular volcanic terrain. Calderas, steaming cauldrons on a frosty morning, loom to your left while granite boulders, grey shadows in the wet canopy, line your right. In late autumn, fog crawls through the ferns and snatches at passing cars.

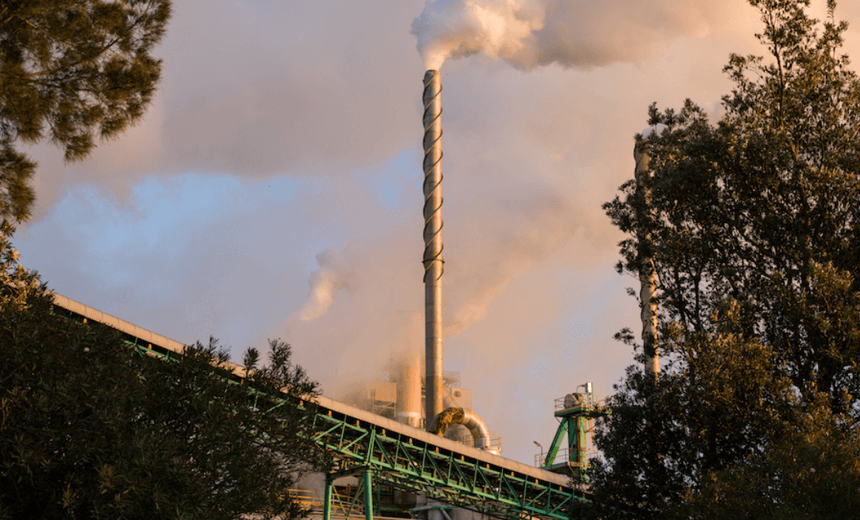

The turnoff to Kawerau is 15 kilometres past Lake Rotomā — former nickname: ‘Suicide Beach’ — where State Highway 30 becomes State Highway 34. Rows and rows of Pinus radiata line ‘the straights’ into town. Pūtauaki, an 820-metre-tall volcano, guards the town’s southern border while Tasman Mill, the largest pulp and paper mill in the southern hemisphere, marks the northern border. The frost flats and pine plantations mark the town’s western edge and farmland rolls out to the east.

The town’s weatherboard homes and Colorado-style mansions sit on top of dozens of abandoned pā, Māori villages evacuated after thick, black ash from the Tarawera eruption poisoned the soil in 1886. Very few locals remember the history. Instead, all that’s left are flattened hilltops, terraced hillsides and strange depressions — old kūmara storage pits — in people’s backyards. The early town-planners paid it no mind, only stopping to consider where they might be building after surveyors discovered ancient hearths in the middle of a subdivision.

I make a terrible travel guide because I can never resist pointing this out. Some people are afraid of ghosts, and the thought of sleeping above the bones of other people is, I’m told, terrifying. Every shadow becomes something sinister. ‘I wish you’d never said anything,’ a mate told me after learning that our parents were living only a couple of hundred metres from one of the earliest sites of human habitation in the Bay of Plenty. ‘I woke up at 3 a.m. last night and thought the cat was saying something in Māori.’

Superstition, or knowledge of history, does strange things, but then Kawerau is also an odd place. My old man is an exercise addict; growing up, the family would nearly every weekend walk somewhere, run somewhere or bike somewhere. My favourite track passes through one of the town’s few remaining wetlands, where the water is freezing cold, sandflies bite at your ankles and grotty sinkhole mud leaches through your sneakers and socks, staining your feet and toes. In summer it makes ideal mountain-biking terrain.

But the track takes you close to the area’s oldest burial caves. In pre-colonial times, Māori would often bury and then exhume their dead, cleansing their bones and hiding them in secret caves, a precaution against grave-robbers who might plan on diminishing the mana and mauri of the tribe. My mate insists, after biking the track with us one weekend and taking the wrong turn and passing close to what we warned were the old burial caves, that ghosts were creeping through the trees, cracking twigs and making the pine branches groan.

‘It’s the ghosts you told me about,’ he said. ‘Honestly.’ But wind is wind, only becoming something different when people impute it with intentions. In truth, Dad is good at spinning ghost stories. Even ‘plausible’ ones. For our birthdays growing up, he would sometimes self-publish children’s books in which my two sisters and I were the main characters. In one story, Pūtauaki becomes an underground spy base and Tasman Mill is the scene of a billionaire’s plot to dump the country’s toxic waste in the local waterways. My sisters and I were not the heroes per se, but the ‘protest’ leaders.

The old man and I were, I know now, too similar in personality and politics, and so our Oedipal struggle began almost as soon as I arrived. One of my earliest memories is defying his instructions not to draw a crayon mosaic on my bedroom wall. Only Mum’s word matters, I remember thinking, so two days later I carted the crayon drawer to my room, sketched a deep green mountain above my bed-head and traced grey chimneys and white smoke along the side wall. The old man was furious, though he never said anything. I was, after all, illustrating his own fictional story.

This is how our relationship would work in the early days: instruction and rebellion. If things ever came to a head, the last word was usually mine. One, because Dad loathes petty rules and the arbitrary power of parenting; and two, because I knew this. Even when he would insist on having his own way, I could always appeal to Mum for the final say. After I drew my masterpiece on the bedroom wall it fell to her to remind Dad that he’d done the very same thing on his first day of school, transforming his desk lid into a canvas.

This was also how the gender roles in our house worked — in reverse. Mum was the primary ‘breadwinner’, providing the main income and exercising the matriarchal and patriarchal authority in the home. It was up to Dad to cook dinners, vacuum and mop, clean and hang out the washing and more. It was up to Mum to make sure the family got by. Not an easy thing to do as a teenage mother. Even harder when your husband was a former patched gang member, a bloke with ‘Mongrel Mob’ tattooed across his forehead, and in and out of work during the family’s early years.

With children of your own, you have to grow up fast. Mum left school in the sixth form, at the height of her years of teenage rebellion. At 15 she smuggled cigarettes home, and she and her mates would walk to school through the back streets taking turns dragging on their rollies, choking as soon as the tar hit their throats. Innocuous enough — nearly every young person smokes, or thinks about smoking, without permission — but four years later Mum was raising a family with a gang member; something her own stable, respectable family struggled with in the early years. In these situations, every parent asks: Where did I go wrong?

People sometimes find these details hard to square. ‘I never imagined that was your life,’ an old flatmate once said. ‘You’re just so… bougie.’ Fair cop. If the government’s social investment approach had been around when my sisters and I were growing up, perhaps our family would have been identified as a target for monitoring and intervention. Teenage mother and gang father in the country’s poorest town — here is a ‘problem’ family. But this is an essay about why things were not as simple as that.

History

Dad became a patched member of the Kawerau Mongrel Mob a year after his own father was appointed the Minister of Works and Energy in the Cabinet of Samoa. His mother, a poet and short-story writer, was working at Monash University in Melbourne after returning from stints in Hong Kong and Mumbai. Neither person knew what the other was doing at the time. It had been more than 20 years since they had last seen each other.

Dad spent the first week of his life in Auckland in a hospital bassinet. For whatever reason, his birth mother, a teenager from a ‘traditional’ Pākehā family in the South Island, did not keep him, and his biological father — an economics student at the University of Otago — never knew. Perhaps it was the stigma of living as a young white mother with an accidental brown child that forced her hand. Whatever the reason, rumours would follow her across Auckland and the South Island.

Dad’s adoptive parents were a working-class Pākehā couple from Thames. His adoptive mother would always insist that Dad — a kid with spotless copper-coloured skin, a sharp jawline, long, soft eyelashes and perfectly straight black hair — was the most beautiful person she had ever seen. But the stigma of adopting not one but three brown children would follow them from Thames to Auckland to Waikato to Kawerau. Old friends refused to talk to them. Other couples would whisper behind their backs: what is wrong with the Godferys?

The family spent their early years in rural Waikato, working out of a magnificent colonial farmhouse. Some nights Dad would wake in the dead of night, not knowing where he was, and sprint down the passage to his parents’ bedroom. The floorboards creaked, echoing as the sound hit the high ceilings, and rain lashed the windows. Cows moaned somewhere in the distance. The sprint took an age. ‘Why are we here?’ he would ask most nights.

Adoption is like a rupture in time, where your connection to history and place is lost and everything feels foreign. Dad’s adoptive parents knew this and, after his father secured a job at the old Caxton Mill in Kawerau, which produced most of the country’s tissue paper, the family settled there. Almost as soon as Dad started school he fell in with the Māori boys without a fixed sense of home: kids whose iwi were from other parts of the country; kids whose families rented on land that had been confiscated from their ancestors only a few generations earlier.

This group would go on to become the core of the Kawerau Mongrel Mob. Lost boys. Yet Dad’s part in it all came as a surprise to some. He excelled at school and his parents had given him everything they could — love, security and more — everything except a past. His Poppa, his adoptive father’s father, understood this. In the family telling he was a revolutionary socialist and an aesthete, reading everything from Lenin to Wordsworth, and a local legend among his mates for taking a crack at Sid Holland during the 1951 waterfront lockout.

In Dad’s childhood the pair of them did everything together, from fishing on the Firth of Thames to fighting over card games. Grandparents are not meant to play favourites, but every week Poppa would head down to the pub to chat about the local gossip, argue about politics and brag about his neat grandson. For a time Dad was beginning to feel like there was a history he belonged to, and so Poppa’s early death was devastating. When the family cleaned out his old house, chucking most of it into the flames — including the socialist book collection — they found a photo of Dad in Poppa’s wallet. His old mates said that the last time they’d seen him he was still talking about his neat grandson.

It was another rupture in time, a break from a past Dad was beginning to feel a part of. From there, Dad’s teenage years were a struggle. His mates were, in their early years, polite chaps, yet they were becoming teenagers with grievances. Dad was still excelling at school, and a few years later was even selected to represent New Zealand in boxing at the Commonwealth Games, but he failed the drug test. His parents were at their wits’ end.

After finishing high school Dad moved to Lake Rotomā, renting a mouldy shack on the lake’s edge. White paint was peeling off the door frames, the back windows were boarded up and weeds were sprouting out of the berm and grabbing at the letterbox. In the 1970s Barry Crump escaped Auckland and secluded himself at Rotomā, spending most of his time racing through the forestry blocks at the back of the lake. One night, after racing through the same blocks, Dad and his friends rolled the car they were travelling in.

The car crashed down a bank halfway between Kawerau and Rotomā, trapping Dad and his mate in the left passenger seats. One of Dad’s Mob mates, a 190-kilogram man-mountain, crawled out of the exposed side, ripped the two right-hand doors off and yanked the others out. As the two nursed their arms at the bottom of the bank, he flipped the car, checked its engine and — instead of waiting for help or hailing a local farmer — pushed the car home with his mates back in the passenger seats, the engine steaming as the morning frost was forming.

I could never figure out whether this was true or whether it was the Mob’s take on one of the yarns Crump would spin at the local pub. In Crump’s telling you imagine the good keen man restarting the engine with a pine cone and a grunt. In this telling, brute strength saves the day. This is the world Dad and his mates were coming of age in: one that did not make as much sense as the world they had grown up in. It was upside-down and inside-out.

In the 1960s, the decade the family made the move to their new home in Kawerau, the Caxton and Tasman mills were putting more than 2000 people to work and were responsible for producing more than 20% of the country’s exports. Trains would carry logs and newsprint to the Port of Tauranga, trucks would transport tissue to suppliers across the country and, with the money from it all, local families were comfortable and secure. In truth, Kawerau was a middle-class town.

But when the Fourth Labour Government took power in 1984, plans were hatched to slash export subsidies and ‘open’ the economy to overseas competition, meaning that the mills would lose their privileged market position. Exporting became more competitive and importing became more attractive. Over the next 10 years, almost a thousand people at the two mills were put out of work. Homes were sold, small-business owners shut up shop, sports clubs closed and school rolls plummeted. The only things that grew were pokie-machine profits, bottle stores, churches and gangs.

In Dad’s new world, not only was his own sense of history displaced, but also one of the few secure things in his life — his sense of home in Kawerau — was in transition. He and his mates could no longer rely on the things their own parents had. A job for life? Not anymore. People who were put out of work found a social safety net that the government had cut holes in. People who were looking to train for new work found a fees system.

Mum’s ancestors had lived on the land surrounding Kawerau for nearly a millennium. Our tupuna is Te Rangikawehea, famous in pre-colonial times for his tribe’s material wealth. ‘Ka kapi nga putahi kai a Pahipoto a Te Rangikawehea’ — ‘Covered completely are the food plantations of Pahipoto of Te Rangikawehea’ — go the lines of a well-known manawawera. In Mum’s early years, her extended family were well known across the central and upper North Island for their extensive kamokamo and sweetcorn plantations.

Mum traces her whakapapa to the area through her father. Her mother’s whakapapa is further north, at Kāwhia, and further north still to parts of continental Europe. During the Waikato Wars her tupuna, a Pākehā, was one of the few European settlers with permission to pass the aukati line, the border between Auckland and the Waikato, helping the Kingitanga government trade with Australian and American merchants.

War is good for business, and Mum’s tupuna went on, through marriage, to become a significant land-owner in the area, only for later generations to lose that land during the Great Depression. Parts of the family may have considered themselves landed gentry; when Mum’s maternal grandfather, who moved to Kawerau in the 1960s, became the union president at Caxton Mill, one of his close cousins sent a nasty letter to the family home saying that their own grandfather ‘would be turning in his grave’.

On the face of it, Mum lived a charmed life. Her mother was the local bank manager, one of the prestige professions in provincial New Zealand, and her father would go on to become one of the bosses at the local sawmill. Their lives were stable, secure and loving. Mum was also the favourite grandchild, which helped. When she hit her teenage years her grandfather would simply give her his car keys with permission to joyride. No licence needed.

Yet Mum was also the first generation of her family to lose te reo Māori. It was her father’s first language, although he never spoke it in the home. She was also part of a generation alienated from its own ancestral land. The family spent most weekends on the road, travelling to roller-skating tournaments, taking camping trips or visiting family or the marae. Each time they left Kawerau on State Highway 30 they would travel past the very land that had been confiscated from their ancestors and ‘awarded’ to military settlers to ‘deter rebellion’ less than a century previously. It was an everyday reminder of a history and a heritage that no longer belonged to them.

Most children never think like this, but Mum was, from her early years, often the smartest person in the room. Although she is, for the most part, unassuming and non-threatening, with wavy black hair, perfectly symmetrical freckles and a warm, welcoming face, she also has an eerie feel for ideas and emotions. Every year at school she would excel, although as each year went by she would become more and more disconnected from the drudgery of ‘the three Rs’.

Mum had always run the show — something that comes across as cute in a kid but menacing in a teenager. During family camping trips she was head cousin, deciding what games to play and how to play them. On one camping trip to Waikawa Bay on the East Coast, the kids laced together some dirty old rope, wrapped it around a sturdy-looking pōhutukawa branch and attached it to a worn-out tyre. They called it a swing. Mum, as head cousin, took first turn. Up, and down; up, and down; up, and crash. The rope snapped and she cracked her left arm on a jagged rock.

Her arm was in a cast for weeks and was a physical reminder of the feeling that she was no longer in control of her life. She was at times disconnected from her past, without her land or language, and her future felt foreclosed. Teachers and adults sometimes struggled to deal with a bright Māori girl. Māori girls were meant to be stupid and submissive, so the reaction some adults had to one who did not submit to their expectations was often racist. Mum was either ‘too lippy’ or ‘too quiet’.

‘Maybe school isn’t for people like me,’ she thought after a confrontation with one teacher. This is how racism’s psychic harms work, diminishing every part of you: smothering your hope for the future; crushing your faith in others; even mutating your own understanding of reality. Maybe I am stupid? Or lazy? Maybe the way I feel — disconnected — is my own fault? Statisticians can capture the outcomes — terrifying incarceration rates for Māori, lower life expectancy and more — but how people get there is often harder to define.

In Mum’s case, perhaps there was a part of her that said she should act out other people’s expectations. After leaving school early she moved in with workmates from the local branch of the BNZ. It was a scandal of sorts: a kid who was on a fast track to university throwing it away to work as a bank teller. Why? Of course, at the time Māori women were never properly encouraged to consider university. The best they could hope for, other people said, was the local bank branch, perhaps moving up to a regional office if you put your head down and did as you were told.

But Mum was more interested in courting Dad, and no one could quite figure that one out either. Why would she, a girl from the local bourgeoisie, court that bloke from the local Mob? Dad would say to her, again and again, ‘I’m no good for you’, but she would persist, tagging along with him to parties and driving out to his house. One night she tagged along on a race through the forestry blocks behind Lake Rotomā, the driver stopping in the giant clear patches where the logging trucks turned around. ‘What’s your mate up to?’ she said to Dad. The answer: ‘He buried his shotgun out here and now he can’t find it.’

If Mum really was, as the racists in her life might insist, just another troublesome Māori girl, then perhaps this was her acting it out. But it was more than that. In the end, both Mum and Dad knew what no one else did: they were entirely similar. Both felt disconnected from their past and that their futures were out of their hands. Love enters the story, too, but that is one for the two of them to tell in their own words. Only a year after all of this, Mum was pregnant with my eldest sister, and a couple of years later I arrived.

Politics

A few months after my fourth birthday, I packed my Thomas the Tank Engine backpack and pleaded with Mum and Dad to leave Kawerau. ‘I saw black clouds and black rivers in my dream,’ I said, crying into my half-packed bag. ‘The mountain’s going to explode today.’ Mum said something reassuring about extinct volcanoes, but I knew otherwise. ‘We have to go,’ I told Dad. ‘I saw it all.’ The old man said something about the last eruption happening thousands of years ago, though this only confirmed my worries: four-year-olds do not see time in quite the same way as adults. Thousands of years may as well mean tomorrow.

Children know that adults are simple-minded. They think in binaries. They talk in certainties. I knew my parents were wrong, and I was going to show them. I took my backpack and a pillow to the sliding door and stood watch. From the back of our old weatherboard house you could spot Pūtauaki’s twin peaks: the western peak with its crown of red and white, an aerial tower; and the eastern peak with its crown of grey and white, a satellite tower. In between the two peaks you can pinpoint the crater lake, a deep green crown surrounded by hardwood forest.

I knew this is where it was going to happen, and so I spent the morning in fear and anticipation. What do I do when the black clouds come? The river is only a couple of hundred metres from our house — is there time to escape when it runs thick with black sludge? I stood there for most of the day, waiting. The hours passed. I packed the dog food, making Argus — our old mutt named after Odysseus’s faithful dog — stand watch with me. I filled water bottles and packed my sister’s bags. I emptied every cupboard looking for some kind of breathing device. Cups with holes in them? That is how you make toy phones. No good. Those funny-coloured inhalers? I knew people use those to breathe. Better.

At 5 p.m., after I’d waited several panicky hours at the sliding door, Mum arrived home. ‘Well, you were right, son,’ she sighed, ‘a mountain did erupt — just not our one.’ That afternoon, while I stood watch at the sliding door with Argus, Ruapehu was spewing black ash and rock. Heavy black sludge — lahars — raced down the mountain valleys. The slopes were hissing as scalding-hot water hit the snow. Ha! I took this as a great victory over Mum and Dad, the non-believers. My timing was right, even if my location had been a couple of hundred kilometres off. Mum and Dad said that at the time they took it as a tohu, a sign.

For reasons of style I decided to arrive on the scene during Matariki, the Māori New Year, when the seven ‘eyes of god’ rise on the eastern horizon. In one of the traditional tellings, Tāwhirimātea, the god of wind, mad with grief at the separation of his parents, scratches at his eyes, ripping them from their sockets and tossing them to the heavens. Every year his eyes appear as a cluster of stars in the hours before dawn from late May to late June. For people who believe in such things, entering the world during Matariki is a tohu.

Of course, in Kawerau there are ‘signs’ everywhere, like the logs people say float against the river current where someone has drowned, taniwha warning keen swimmers to stay away. But my tohu were more of a family joke, a fun explanation for my precociousness. Poor people struggle to find the time to read the stars, interpret dreams or invent curious stories about taniwha concealed as logs, let alone take such readings, interpretations or stories as a true account of how the world works. Your energy is aimed at surviving, the day-to-day pressure of making ends meet. Poverty and struggle tend to take the magic out of the world.

My sisters and I spent our early years on a diet of vegetables and mashed fruit. We were children of the Mother of all Budgets. Dad was in and out of work, and the old Family Benefit scheme — the weekly, universal payment that sustained thousands of families from the 1940s to 1991 — became a means-tested family tax credit available only to parents in work. Around this time, I suspect, Mum and Dad made an unspoken pact: we are going to find a way to get this family thing right, somehow. Mum went off cigarettes and parties. Dad became a teetotaller and, on orders from Mum, left the Mob.

This is how the lower classes were expected to respond to hardship: with individual sacrifice and piety. In a traditional telling, this is where our new family transcends its circumstances through grit, discipline and sheer bloody hard work. Mum, who today is a scientist working on developing fungi to break down dioxins in the soil on old industrial waste sites, the hero out of one of Dad’s children’s stories, is a striver. Dad, an elected local-body politician, similar to his own biological father, is a hard grafter.

But this is not a traditional telling. As young people Mum and Dad felt disconnected from their own histories, but they were also beneficiaries of them. When Mum went to university as an adult, her parents would often cover the family shortfalls: extending loans that became gifts; even buying the family home from Mum and Dad so that we could upsize to a new, bigger home a few blocks away. Dad’s parents paid for the last family trip to Samoa, where we keep in contact with his biological family.

In one sense, this is what a ‘social investment approach’ cannot account for. History. In another sense, it is what the politics behind a social investment approach encourages: the family, not the state, is reproducing its class configurations generation to generation. The state was absent in the material lives of our family and the material lives of families in similar circumstances. The difference is that Mum and Dad had other means of material support. Their story is as much about luck and circumstance as it is about old-fashioned capitalist hard work.

I left home at 13 years old, around the same time that Mum started studying. Nan and Koro were sending me to boarding school. I was looking forward to it — it was an escape from the tyranny of parental authority — but my stomach was still churning. Boarding school is a life of regiment and politics. There is a set wake-up time, a set bed-time, a set study time, set meal-times, certain ways to address certain people, a duty roster, and a hundred or so other boys who you are meant to get along with. This is what moving from the town to the city must feel like: crowded and foreign.

Yet I still spent most weekends at home, less than an hour’s drive away. As keen as I was to escape it, it was also home. Most Fridays, Dad would arrive at school in his white work van and ferry the Kawerau boys back home. ‘Chur, Mr Godfery.’ ‘Shot, sir.’ Dad was out of the Mob, but tattoos still ran up his arms and across his forehead, and the rest of the kids knew it. My room-mates were always keen for ‘gang stories’, mean fights, piss-ups and the like, though I never had any to tell. At times I would think about making some up, if only to stop the questions, but I decided that it was never going to convince anyone.

To outsiders, our lives seemed incoherent. People would say things like ‘you weren’t what I was expecting’ or ‘it must have been hard for you’. But in truth my sisters and I lived privileged lives, at least in comparison with other people we knew in similar circumstances. Although Mum and Dad were poor for most of our childhood, we enjoyed all the privileges of the middle class: overseas holidays, South Island skiing trips, grandparents with flash European cars and more.

Naturally, I was embarrassed about my mates at our decile 1 primary school finding out that we were not as poor as they might assume. Every Monday and Friday after school our Nan — Mum’s mum — would pick us up in her Range Rover. I would pack up my things as slowly as I could and sneak out the side entrance, or pretend to have forgotten something and double back to avoid anyone discovering the truth. ‘Far, you’re rich,’ a mate said after spotting me in the passenger’s seat the day before. ‘Can we come around to your house?’

On paper it always seemed as if we were going to become problem children; a teenage mother and a gang father living in what others said was the ‘DPB capital of New Zealand’ and a ‘gang town’. But reality is almost never that simple. This is the problem with politics as data. While it can account for teenage pregnancy, gang membership and more, only history offers a full perspective on those same social facts. Politics and people’s lives happen across time, not within a data point.

History is the better guide for making sense not only of people’s lives but also of politics. This is as true for a conservative like Burke as it is for a radical like Karl Marx. ‘Men make their own history,’ wrote Marx in his 1852 essay ‘The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon’, ‘but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.’ For Marx, capital — that thing making the capitalist economy go around — was ‘dead, congealed labour’ living ‘vampire-like’ by sucking value from living workers. In his account, capitalism is the dominion of the past over the present, a ‘werewolf’, ‘vampire’ or ‘animated monster’ reaching from out of the past to consume the present.

My first name is Mum’s maternal surname. My middle name is the name of Dad’s best mate in the Mob. My surname is Dad’s adopted name. Each name is a connection to a different past. ‘Morgan Gavin Godfery, that’s a pretty Anglo-Saxon name for a Māori,’ one author told me at a writers’ festival last year. On that, he was right — it’s a strangely traditional name for a young Polynesian — but in the context of my family history it makes impeccable sense. Everyone lives a messy, unusual life. There is no normal. The sooner our politics understands this, the better off we will all be.

The Journal of Urgent Writing 2017 is edited by Simon Wilson (Massey University Press, $40) and available from Unity Books.