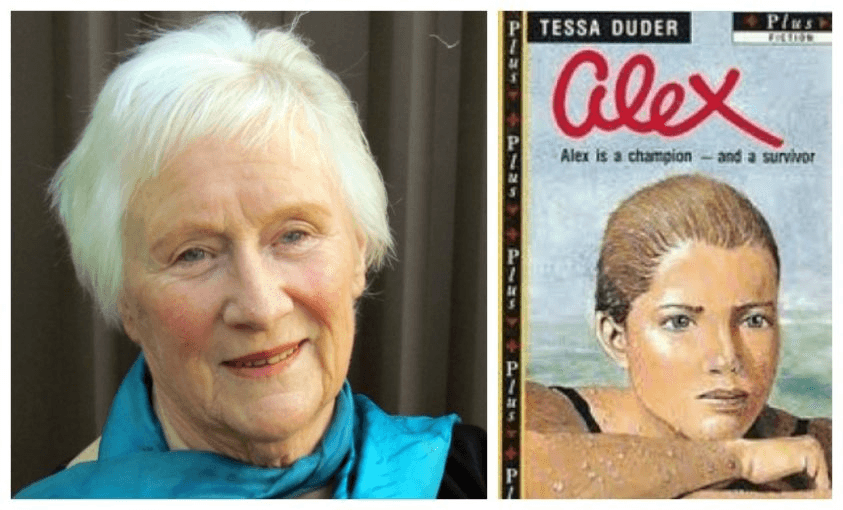

All this week the Spinoff Review of Books looks at the new memoir by former Green MP Holly Walker. Today: we asked author Tessa Duder to respond to the chapter which credits her classic YA novel Alex as a formative influence.

During the winter of 1986, I wrote the first book of the Alex quartet. Unlike today’s would-be novelists attending creative writing workshops and star-studded writers’ festivals, I’d never heard of three-act structure, character arcs or inciting incidents. In hindsight, I was relying on instinct from a life-time’s reading, experience as mother of four, my feminist leanings, a natural curiosity, and persistence.

Alex appeared in my head almost fully formed like some mythological goddess. I remember the moment well: Kuala Lumpur, 1981. She would be a tall, stroppy schoolgirl who wants to swim at the 1960 Rome Olympics, but needs to sort herself out if she is to beat a serious rival. She overcomes injury, learns discipline, but fronts up to the crucial selection race still recovering from the tragic death of her first love. She comes from behind to win, of course; if she’d come in second, a shrewd eight-year-old boy once told me, “Well, then the book should’ve been called Maggie.”

The idea, lying fallow for five years while other books got written, was completed in eight months and sympathetically edited by Wendy Harrex. Oxford University Press published in September 1987. Aged 46 and no longer slim, I declined their publicist’s invitation to arrive at the launch in Takapuna’s Pumphouse dripping wet from a swim across Lake Pupuke but was delighted that famed sports journalist TP McLean accepted an invitation to do the launching honours. I suppose it was a signal that Alex was something a little special.

In the 30 years since, I’ve followed my “take-off” novel’s surprising journey. In print for nearly all of 30 years. Three more books to complete her Olympic odyssey and transition to adulthood. Two major awards. American, Australian and UK editions. Translations into Catalan, Dutch, Afrikaans, Danish. Tom Parkinson’s movie adaptation premiered in 1993. Around 2010, Alex was chosen by a TVNZ arts programme (remember those?) as one of five finalists for “Kiwi fiction’s most memorable character”, along with Beth and Jake Heke (together) from Once Were Warriors, Wal and Dog (separately) from Footrot Flats, and the one and only Fred Dagg. If I remember rightly, Dog won.

Does this explain the countless letters, emails and conversations telling me that the book kept them awake until 2am, that they wept buckets and hated me for killing off Andy? That they’ve read it over and over till it literally fell apart, for inspiration, solace or courage before a big race?

In response, I’m flattered but really have no idea why my Alex apparently leaps off the page into people’s hearts and minds, adults as well as children. She is not always particularly likeable. Holly Walker describes her as “an overachiever … hopelessly over-committed … headstrong, opinionated and non-conformist”, capable of “falling apart in a screaming heap”. Adding firmly, “She is a feminist.”

Now this is interesting, because in the late 1950s staid and patriarchal New Zealand, “feminist” was hardly a label in common parlance. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique didn’t appear until 1963, and American “second-wave” feminism didn’t really hit New Zealand until the early 1970s. I didn’t encounter Friedan until around 1974, and by then I had four lively daughters aged two to eight. Immersed in Playcentre and family life, I cheered on the increasingly powerful voices of Sue Kedgley, Sandra Coney and Judith Baragwanath, but only from afar.

Yet Holly is right: Alex is a feminist, as I became during the 1970s thanks largely to Frieden and Greer, Coney and Kedgley. I was a first-born child with supportive parents, eager to see me achieve as a swimmer. The egalitarian swimming community treated boys and girls exactly the same. Indeed, the Kiwi swimmers of the 50s who drew the big crowds were nearly all female: Jean Stewart, Marion Roe, Philippa Gould, Jennifer Hunter. When I joined the Auckland Star as a cadet reporter early in 1959, I took it for granted that male and female cadets would be treated on equal terms. (The Star’s chauvinistic barricades had been breached by novelist Ruth Park thirty years earlier; the New Zealand Herald held out until 1959 when Marcia Russell signed on as a cadet.) I recall the only reporting job not assigned to the Star’s female cadets was meeting incoming passenger liners at dawn out in the Rangitoto Channel. Wearing “slacks” on the job was not allowed, you see, and however fit, young women in full skirts climbing a ladder up the side of a moving ship might prove a worrying distraction for the pilot boat’s deckhands.

Was there a certain innocence about these formative years, both for me personally and as experienced by Alex? Certainly, as 1950s New Zealand is often fondly remembered as a decade of innocence, decency, order, prosperity – the calm before the stormy 1960s. But it’s only blokes who rhapsodise about the ’50s; women of my generation know otherwise. We remember being patronised or ignored, the casual chauvinism and petty restrictions and shamefully low expectations of girls. Factory or shop work, nursing or secretarial, teaching if you had a diploma or degree. Perhaps some OE thrown in before a white wedding and children, your own weatherboard home to do up. Happy ever after. No-one asked what you thought you might be doing at 45 when the nest had emptied out.

Given my growing awareness, it’s probably no surprise that my first two novels, Night Race to Kawau and Jellybean, are feminist in theme and tone. They were intended to be, as was Alex. Writing in mid 80s about Alex’s experiences during 1959 gave me licence to make her braver and more interesting than I ever was, despite my swimming experiences and unusual career choice of journalism. She rails against injustices and prejudice. In the second book she scandalises a Rotary luncheon with some blunt opinions about sham amateurism in sport. She stands up to pompous officials and her rival’s scheming mother. She’s furious with her best friend bowing to her father’s insistence that she settle for a few years’ nursing rather try for medical school, while her less capable brothers are encouraged to head for careers in law and accountancy.

Which small vignette (pretty much true) brings me to reviewers who blithely assume that Alex is semi-autobiographical. How do they know this? Holly Walker, bless her, ascribes her identifying so completely with Alex to my ability as a writer to reach, not inside the reader’s head and heart, but into my own. She realises that what her 10-year-old self had connected with so clearly was “authenticity”.

That authenticity took time and effort, reaching back into forgotten memories, digging out old scrapbooks and contemporary accounts of the golden sporting era of Phillipa Gould, Snell and Halberg. I gave the manuscript first to my old swimming coach.

I said, “Jack, please be frank – does this ring true?”

“My dear girl,” he replied, “of course it does. It’s all happened.”

But authenticity doesn’t mean “semi-autobiographical”. Witi Ihimaera once shared a similar grievance that a reviewer declaring “semi-autobiographical” seemed almost like a put-down – that somehow it was more comforting for reviewers and readers to believe that this affecting work of fiction was actually just drawn from real life, merely reportage. Otherwise, how could ordinary-seeming people like us actually make up something so powerful, so moving or even life-changing?

I made a lot up. As a swimmer training for selection for the 1958 Empire Games, I had no serious rival for my place on the team, no broken leg, no melt-down resulting from exhaustion, no devastating loss close to a big race. I will admit to being in love for the first time, and this affair ending if not with a death but still unhappily; so some heartbreak and authenticity there. But my hackles rise when some Australian academic asserts, in a short review in 1001 Children’s Books You Must Read Before You Grow Up, that Alex “is loosely based on the life of the author …”

How, pray, can this Aussie person be so certain? Oh sure, she’s read my CV and I too was a schoolgirl “overachiever” and was – am still – famously opinionated, but the similarities are superficial. Only I know what is based on memories, what is researched, what has been playfully expanded from facts or what – the largest category – is actually pure invention.

Alex Archer is an amalgam of two of my daughters (not saying which), the indomitable Dawn Fraser and some parts of me. I created her as a late 1950s teenager learning how to take risks and manage her life, a deliberate rejoinder to YA novels of the time that far too often featured gutsy male heroes having all the adventures and girls as followers, victims, passive, conformist and short on ambition.

This year is Alex’s thirtieth anniversary, but I don’t expect any fanfares from her three publishers over the decades. Editors have moved on, earlier commitment to an author evaporates, even of a classic. The 2012 Whitcoulls re-issue seems to have slipped out of print. I am grateful that Holly’s delightful book The Whole Intimate Mess: Motherhood, Politics and Women’s Writing is providing a celebratory moment.

More about Holly Walker and women in Parliament this week on The Spinoff Review of Books:

Monday: An excerpt from Holly Walker’s memoir The Whole Intimate Mess

Tuesday: Green Party candidate Chlöe Swarbrick in conversation with Holly Walker

Thursday: The Whole Intimate Mess reviewed by former Act MP Deborah Coddington

The Whole Intimate Mess by Holly Walker (Bridget Williams Books, $14.99) is available at Unity Books.