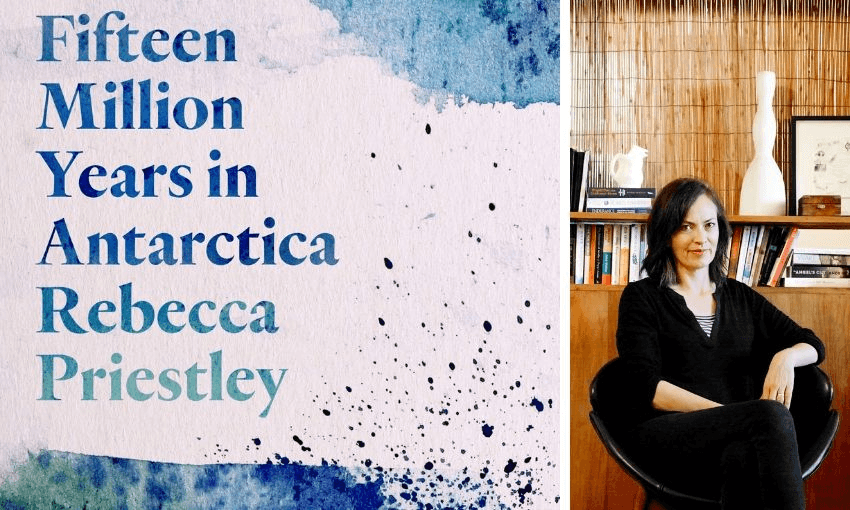

In this extract from a chapter called ‘Deep Time’ in Rebecca Priestley’s new memoir, Fifteen Million Years in Antarctica, Rebecca remembers her peculiar, legume-heavy, art-saturated childhood in Wellington. (And a note from the author: if anyone has a painting from Ruth Priestley’s Antarctic Dream series, Rebecca would love to hear from you.)

I grew up in an old house with spiders’ webs on the ceilings and art on the walls. Some of the paintings—large abstracts in muted browns and greens and oranges—were by my mother. They were weird and dark and I didn’t much like them, but one of her pictures sticks in my mind. It was pencil and watercolour on paper. A small faceless female figure stood, half obscured, beside large rectangular blobs stacked on top of each other. It was on the living room wall above a book case that held pewter beer mugs from Malaysia, brown ceramic drinking mugs from Portugal, and paperback books in which I had furtively practised ‘handwriting’ as a pre-schooler. The picture was from a series called Antarctic Dream.

I’m not aware of ever thinking about the picture, but I remember the feeling it gave me. It made me uneasy, and it drew me in, that naked woman—half a woman—standing beside a large rock. I couldn’t tell if she was in danger and needed rescuing or if she had escaped and was hiding. Perhaps this dreamlike and colourless landscape was her world.

Korokoro

I started school in London. As a newly single mother with two pre-school children, my mother, Ruth, had embraced the freedoms of the 1970s, and had taken us to live in London for six months where she took sculpture and dance classes and sold hand-painted and embroidered clothes to north London boutiques. When we returned to our rented house on a hillside acre in the ‘semi-rural’ suburb of Korokoro in Wellington, a young family were living in one room of the house: Jane and Paul and baby Toby.

‘This is our house,’ I proclaimed as they greeted us at the door. My hostility was short-lived—it was fun having a baby around and soon sharing a house with another family was what we did. We had returned to New Zealand in summer, but it was months before Rachel and I would venture further than the rectangle of cracked concrete outside the back door, the size of our London backyard. Once I was confident in our expanse of garden I would run from the house, past an enormous veggie patch, past an enormous kōwhai tree that always bloomed in time for Rachel’s birthday, past a high bank crawling with banana passionfruit and topped by damson trees. At the end of the garden, next to a line of trees that marked the next-door boundary, was an old wooden shed. If you dared look inside, you could see—through the darkness and the ubiquitous spiders’ webs—dead seagulls hanging from the ceiling. It was art, or somewhere in the process of becoming art.

Inside the house, in Jane and Paul’s room, was a large stuffed owl looking down from a high dresser. In the living room, more birds watched me: black-and-white photographs of the birds and Paul’s own drawings, all safely behind glass.

We were often taken to exhibition openings where we would inevitably have our photos taken. In the London scrapbooks Ruth made for us—they continued for a few months after our return—is a clipping from the front page of the Dominion from August 1973. It shows a large picture of Rachel, knees and hands on the floor, forehead resting on a block of rubber on top of two bricks. Beside the installation was a sign: Kneel on pillow and bounce forehead against rubber until enlightened. Sometimes it was Ruth’s art on show. In their coverage of a ‘preview to their exhibition of paintings’ by Ruth and Joanna Paul, the newspaper printed a photo of me, aged five, and Rachel, three, wearing embroidered clothes and looking straight at the camera. Rachel is smiling. ‘These wistful little girls attracted almost as much attention as their mum’s paintings,’ said the caption.

Some of the openings I don’t need a picture of to remember. One time the architect Ian Athfield and another man—both grinning behind their beards—strode into a gallery, where the men all wore jeans and the women dresses and everyone had long hair, and poured a bucket of cold baked beans onto the floor. Straight away Rachel and Toby got down onto the floor and used their fingers to draw patterns in the beans. Toby put a few beans in his mouth. It was art. By now I knew the photographers were watching and I was too self-conscious to join in. Besides, I was the oldest. I didn’t do finger painting.

We’re driving along Petone foreshore. Paul—long brown hair, an enormous moustache, jeans—is in the driver’s seat and I’m in the back with a friend. Paul stops the car—he’s barely pulled over but it’s a wide road and easy for other cars to pass. I don’t know if my friend realises what’s happening, but Paul is out of the car, running back a ways, picking up a dead seagull from the road, and putting it into the boot. I try to stare straight ahead. I guess I’m aware enough to hope my friend doesn’t notice what’s happening, but my difference from the other children at school is too fundamental for me to experience the social mortification that might be expected.

Most of the time it was Ruth driving the car. Or sometimes Jane. Paul moved to Australia after a few years. I spent most of my childhood with Jane and Ruth, two single mothers, and Rachel and little Toby. Sometimes we had pets. A mother cat and her litter of kittens. A sheep attached to the clothesline by a length of rope and one of Ruth’s leather belts. A rabbit that escaped from its hutch one day. A pair of goats that ate all the fruit trees and knocked down the sheds. A tame magpie that turned up and stayed a few weeks.

Locals called our house ‘the commune’. My mother was a ‘Ms’, or just ‘Ruth’. I wore handmade or secondhand clothes and we ate brown rice and lentil curries. I didn’t even wish I was like the other kids; I just knew that I wasn’t. Being a white- socked, neat-haired girl with a Mr and a Mrs for parents and Mallowpuffs in the kitchen and a colour TV in the living room was way beyond my reach.

*

It’s raining. Pouring down. The kitchen, a long lean-to with windows looking out to a concrete courtyard and a couple of old sheds, is peppered with buckets and cooking pots to catch the drips. We’re all a bit excited because Ruth is up on the roof in the rain, wearing an oilskin parka over her jeans and woollen jerseys, and a colourful hand-knitted hat. I want to go up too but I’m not allowed. Not while it’s raining. She’s ‘fixing the roof’. Somehow, her efforts—with strips of canvas ripped from her painting supplies, and oil paints applied thickly—do the job, and the dripping subsides.

The mother of my childhood, of my memories of those years, was a strong, capable and outspoken woman. A mother who fixed roofs, cut firewood, and dug the garden. Jane worked at the Downstage box office and had floaty clothes and glamorous friends. She was slight and somewhat ethereal and made Ruth look bigger. Ruth was in the habit of saying to shopkeepers or authority figures ‘you don’t need a penis to [insert male-dominated activity here]’. This was mortifying to me, of course—she’d said ‘penis’!—but the sentiment stuck with me, and soon I was piping up at school when a teacher would suggest we borrow ‘your dad’s tools’ for some activity, or bring in ‘one of your dad’s cigarette boxes’ for some art project, though of course I didn’t say ‘penis’. ‘Or your mum’s,’ I would mutter, quietly, too shy to speak loudly but annoyed at this assumption and the way it excluded me, who lived with no dad, not mine or anyone else’s, at home.

Our house was a wooden Victorian mess up a long shady path covered with pine needles and traversed by tree roots. We called it ‘the Path’. At the bottom of the Path, next to a large wooden garage—perhaps it used to be a stables?—was an old black telephone with a winder. If you wound it hard a matching phone would ring in the laundry of the house. Jane and Ruth would use it when getting off the bus or out of the car with the groceries, to ask for reinforcements to be sent down the Path to help.

One time Ruth sold the car she’d been driving for some months for One Hundred Dollars, an almost mythical sum of money. She celebrated by buying a crate of ‘champagne’, which was what we called sparkling wine, and ‘a side of lamb’, a phrase that didn’t mean a lot to me but which meant there was roast lamb for dinner, which everyone seemed to think was exciting. She also gave Rachel and me a dollar each to spend.

Our life was mostly frugal, but events like this were huge fun. There was a sense of celebration, of Fuck you to expectations and norms, a bit of harmless irresponsibility that I liked and held on to.

*

One day, shortly before my mother, sister and I left for London, my father took me to his work at the Ministry of Works’ Central Laboratories, where he was head of structures. When his colleagues asked the inevitable, ‘How old are you?’ I replied—just as Dad had coached me to— ‘Four point nine five.’

It got a laugh from his colleagues, all male engineers, who I’m sure appreciated the accuracy of my reply. I liked knowing I was 4.95, though I wasn’t 4.95 for very long. I shared an affinity for numbers and precision with my father. I liked yes and no problems. Rights and wrongs. Facts. For my eighth birthday my father gave me a big orange alarm clock that I kept beside my bed. He had checked with Ruth first, saying he planned to give me a clock. ‘Unless you would object to knowing the time . . . ?’ he had offered, mistaking her for a hippie, which—given that she worked, voted and financially supported herself and her children—she insisted she wasn’t. Sometimes Jane and Ruth went on dates with men. Sometimes there were boyfriends. Alex, who was a builder, made us a slide and sandpit. Bryan, a DJ, gave me his childhood stamp album. Once a year or so there would be a ‘working bee’ and bearded, denim-clad men would arrive with chainsaws to cut down a pine tree and chop it up for that winter’s firewood.

*

I probably met Peter Barrett at a party. In those days, there were lots of summer garden parties that started in the afternoon and went on until after dark, at which long-haired adults would drink and dance and children would run around in packs, climbing trees or making forts, returning to the house every hour or so for food. Peter and Ruth dated—or whatever it was people did in the 1970s—for a while when they were each between marriages. Peter was a tall, good- looking man with a beard—essentially, he was the same as just about every other man in that scene—but he wasn’t an artist; he was a scientist, a scientist who went to Antarctica.

I don’t have many specific memories of him. Once when he returned from a trip to New York he brought me an Electric Company magazine, which I enjoyed very much. It was significant to me to know someone who was an Antarctic geologist. I knew that Antarctica wasn’t just a setting for heroic journeys; it was a place you could go for work. And, just as importantly, it was a place you could return from.

Peter worked in the geology department at the university and one summer set Ruth up with a petrology microscope and some thin sections of rocks from Antarctica, Finland and New Zealand. I didn’t know what they were at the time, but the large oil paintings she did that year—big blobs of brown, oranges, purples and reds in a series called Through Rocks— were magnified minerals from the slivers of rocks she saw through the lens.

A decade later I was at university, looking down the same microscopes and drawing what I saw, not for my art but for my petrology class.

Fifteen Million Years in Antarctica, by Rebecca Priestley (Victoria University Press, $40) is available at Unity Books.