The Monday Extract: A harrowing personal essay by Christchurch poet Jeffrey Paparoa Holman from his new memoir.

Even before I took LSD with a poet friend I was becoming unhinged. It was as if I just didn’t care; with a few cans of beer on board to dull the rational sites in the brain, dropping a trip seemed like a good move. Fortunately, after two attempts at flying, the supply dried up and I lost interest; it was too unpredictable. I could see the shimmering lyrics of Jefferson Airplane in the air of the room. There seemed to be a living personality in the wallpaper patterns. My flatmate’s boxer dog turned into a raging rabid monster and I found myself in the bath, minus the water, eating carrots.

I came back to my saner self on a night in May as Lee woke me and said, “Let’s go!” Staying with her through the labour and seeing my daughter born was far and away the superior trip. I can still feel traces of this in the poem I wrote to celebrate her arrival —

stunned

by all that made you look at least

ten million years old, from your

mother’s softened vitals to

your female mammal sleeping eyes.

The poem would soon appear in print. David Young agreed to go ahead with a first book of poetry, to be shared with my former teacher, David Walker. Fragments 5: Two Poets arrived in a cardboard box on the table in Huxley Street in late 1974. I could hold in my hand a book that held my work.

I needed that book, if only for the affirmation that somebody else believed my writing was worth enough to place in the public arena, that I might keep going and develop through this first step. It bandaged and splinted my woeful self-belief and kept some hopes alive. It would be 20 long years before another book would follow, but for now I had copies to sell at readings and give to friends, a sliver of evidence that I could write poetry.

Instead of pressing on with my writing life, my next move was to apply for a job as a psychiatric social worker at Seaview Hospital in Hokitika. To grow as a writer and heal as a human being, it was probably the exact opposite of what I needed to do.

Snatches remain of the interview that got me the job: the long drive over to the Coast in Alan’s borrowed Holden wagon with its shiny gear indicator on the steering column; the confident nurse waiting with the other applicants, sure the job was his as he winked at staff passing by; the board member who asked me if the Religious Studies paper from my abandoned degree meant I would be proselytising; and later, my genuine surprise when they wrote and told me the job was mine.

One more time, we packed up to move house. I hired a truck and drove our worldly goods over the Lewis Pass, depositing them at the nurses’ home where we would have temporary shelter, and then drove back to Christchurch. We loaded the few remaining bits and pieces into our old grey Commer van, complete with cats and chickens, and wobbled off into the teeth of a pelting rainstorm in the Lewis that swamped and stalled the windscreen wipers. The rain was so fierce and thick in the dark, it was like drowning in a whirlpool.

The 5th of June 1978 is a day that has never left me. Overnight, Lee had taken off for Christchurch in our old Austin van, driving the Otira-Arthur’s Pass road at the most dangerous time of the year. The van hit black ice not far from Aickens: she lost control, left the road, was thrown out and killed.

Early after daybreak the accident was discovered and by 8am there was a knock on our front door and two policemen on the step. They broke the bad news and asked if I could go with them to the hospital mortuary and confirm it was Lee. They were kind, firm, respectful, deserving of compassion themselves in their grim work of announcing doom.

We had a friend staying who offered to look after the kids and I rang my mother, asking her to come as well. I entered that shock zone where a cushion of unreality surrounds us and the moment becomes all there is, swamped by chemical waves of emotion that will return as grief in the hours and days and years ahead. The dead are different: they are no longer us, they are them — it was her and not her. Somewhere beside that icy road under the gaze of the stars, that animating magic Lee possessed had left her. I had seen death before, seen my father die, but this was different. My life changed in the moment the sheet was lifted from her face. Her death stared back at me, as if I was seeing a vision of my own end. There was no way to reply, for either of us.

The next few hours and days live on as a series of stories: there was shock and there were tears, but you can’t truly describe grief and mourning. We can only feel it: it is embodied, it is anything but words, it shakes and trembles our whole being, which is why the bodily embrace of the bereaved one is the only useful resort of the comforter. I was hugged and held, as were our children: many people came to the house to mourn with us, themselves in shock and in need of comfort. My co-workers from Social Welfare appeared too, letting me know I was off duty on full pay. I would never return.

In conversation with the funeral director, we clothed Lee for her final days in our sight with a long black dress I had bought for her, outlined with poppies. As she lay in state like a queen of Egypt, you could be forgiven for thinking the dress was chosen for that moment. On the day of the funeral service, the undertakers brought her in the morning to the house; we carried the coffin up the steep path and placed it in the sitting room where all and any could come for the remaining hours and make their peace and farewells. Funerals can be wildly eclectic gatherings, bringing together people from all times, places and cultures on life’s journey. This one was no exception, with everyone from a conservative Christchurch accountant, Lee’s parents from the Depression and Second World War generation, right through to dreadlocked alternative lifestyle veterans, reading and chanting over the open coffin from The Tibetan Book of the Dead.

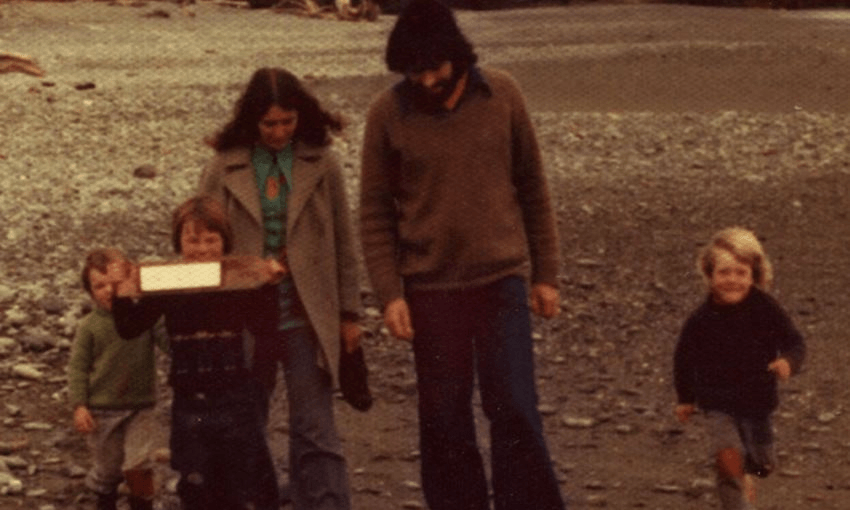

I wasn’t of a mind to shield our three children from the reality and they were all able to see their dead mother, albeit privately. It is something I have learned long since: Māori navigate this passage from life to death with far greater wisdom and skill than Pākehā, in the ritual of the tangi. Kids are included here, learning that death happens in life and is part of the process. Not all of those around me approved my handling of Lee’s departure, but I followed what I felt was human need.

Back at the house in Runanga, the locals had come in to help with food and drinks and my family were there too, looking after the children. The house divided itself pretty much along cultural lines: mainstream and alternative, the former down the back in the kitchen, the latter in the lounge up the front, legal drugs and suits at one end, ganja and Bob Marley braids at the other. Lee’s family and her ex-husband, in their own world of shock, were unlikely to mingle intimately with people living along the Coast road on the proceeds of pottery and weaving. I shuttled between my adopted tribes and tried to keep myself together.

Copious amount of ganja lit up at the front of the house. I had to run around telling my hippie spliffers to cut it out. I had good reason for not wanting my suitability as a parent to be questioned. In the end, I left them all to it and went for a drive down to the beach at Rapahoe. It was Bill Mathieson who got hold of me that night and told me straight I needed to mend my fences, then and there, in the loss of my fiery lover who he too had loved. He knew it was possible to love more than one person at the same time, to love many; he knew it because that was how he was. He was pointing out to me that Theresa was there, she had come out of love into the eye of the storm.

When I saw Lee dead in the Grey

Hospital morgue, was she pounamu

on the beach because

the broken wave was spent? No matter

how long or how hard I’d held her

she’d never warm to me the way

this jade heats up in my grip.

Lay it back on the desk

and it keeps what’s left

of my touch for near ten minutes.

The woman I loved lay stiff

when I kissed her brow, cold

as the frost she skidded over

into the broken-backed abyss.

An edited excerpt taken from Now When It Rains by Jeffrey Paparoa Holman (Steele Roberts, $35), available from Unity Books.