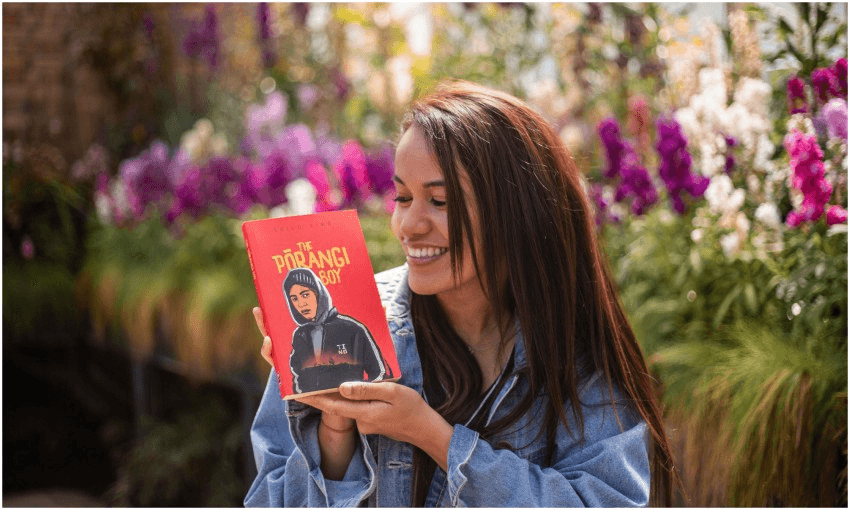

The Marae TV journalist tells the origin story of her debut novel, a young adult book releasing this week.

Patricia Grace wrote a story called “It used to be green once” and every year my Pākehā teacher would pull it out in English class and everyone would laugh at the poor Mowri family with 10 kids who ate holey fruit and had a shameful mum who drove a green bomb.

I come from a family of four kids and I didn’t even know what holey fruit was. Also, my mum drove a silver Mitsubishi with a TV installed at the front. But still, I was one of the only Māori in the class and so the other kids gave me looks as we read the same narrative year after year. The problem is not the story itself, because Patricia Grace is literally a queen, the problem is that it was one of the only Māori stories being told at that time.

The single story creates stereotypes. And the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.

– Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

The first time I was called pōrangi I was seven years old and had locked myself in the backseat of Dad’s car at our marae in Te Kūiti. Even though Dad would tell me “this is your home”, it didn’t feel like it because we only came back here when someone died and also my cousins who I had just met threw my shoes up a tree and then called me pōrangi.

I didn’t really understand what pōrangi meant, all I know is that Aunty Ngaire* was called pōrangi too. She had missing teeth and a moustache line above her top lip. “Hullo Monique,” she would say when she saw me. “My name is Shilo,” I’d tell her, over and over again. Once we were down at the urupā and she crouched down to pee without warning. Everyone looked the other way. At her tangi I kissed her on the cheek and told her sometimes people called me pōrangi too but it didn’t mean it was true.

The title of this book was never meant to have the word pōrangi in it. I wanted to give it a friendly title like “The adventures of Niko” with a nice-looking boy on the cover so it could sit on the front stand at Whitcoulls looking shiny and pretty. Be careful of using that word in your book, my brother, the only fluent te reo speaker in my family, told me. Why? I asked. Pōrangi can mean mentally ill, he said.

The word pōrangi has been deep-rooted in my mind since childhood. It is a word that tells a person’s story with multiple layers and complexities. When I first saw the cover of The Pōrangi Boy, I thought it was too bold, too confronting. I worried that people might stereotype the hooded boy on the cover as a gang member and go oh no, here we go, another mowri story about gangs.

“I showed the kids your cover in class today,” Mum told me. She’s the deputy principal at Moerewa School, a decile one school where the role is 100% Maori.

“One boy put up his hand and said, ‘He looks like me.’”

When I was younger I read an article in the local paper about Ngāwhā prison. The government built a prison in Ngāwhā and the community occupied the land in protest. One of the reasons (among many) Māori protested was because some believed it was the taniwha’s home. The only time I had ever seen a taniwha was the Northland rugby mascot running around the field.

“Is the taniwha real?” I asked Mum one day.

“I remember when I was a little girl and I was swimming in the river,” Mum said. “I put my head under the water and I saw two big red eyes coming towards me. But I don’t go around telling people that.”

“Why not?”

“They’ll probably think I’m pōrangi.”

Here we go again, I thought. That word. Pōrangi.

The story of Ngāwhā prison followed me into adulthood. Three years ago I was living in Mount Maunganui and working on The Pōrangi Boy. I knew I wanted to base my book on what happened in Ngāwhā but how could I when I didn’t know the real story, only what I read in the media? I found the number of one of the lead protesters and gave her a call.

“Hello?” A lady answered.

“Kia ora! Can I speak to Riana Wihongi please?”

There was a long pause.

“Riana passed away.”

I felt terrible and apologised profusely. I told her I didn’t actually know Riana but I was writing a book and I was inspired by the protests at Ngāwhā prison and wanted to know the full story.

“Well, I’m one of Riana’s friends and one of the lead protestors.” Her name was Toi Maihi.

“Come over to my house and see for yourself,” she added. The next day I drove eight hours, with only $200 in my bank account, to Kaikohe.

Maihi had kept every newspaper clipping, and photos of everything to do with the Ngāwhā prison, in a scrapbook. Her hands trembled as she flipped each page, retelling the events like it happened yesterday, the trauma still there. Maihi, with many other Ngāwhā locals, fought for years to stop the prison in Ngāwhā – a $100 million government project. Court battles, trips around the country to other iwi asking for help, multiple hīkoi, hui, and protests.

She showed me a photo of a kaumatua. Two police officers are walking alongside him.

“I can’t remember his name,” Maihi says. “I had a stroke, my memory isn’t all there. But I remember he was blind. He was one of the elders that were arrested for protesting.”

That’s someone’s koro, I thought. Imagine being a kid and watching your own koro get arrested and taken away by the police. Toi then showed me an article where a local Pākehā MP said he was “absolutely delighted” Māori were arrested.

I drove back to Mount Maunganui with questions reeling in my mind. Why doesn’t our country know about this? Why aren’t our kids learning about this? Why am I learning only the full story now, as an adult? And then it dawned on me there are so many stories like Ngāwhā that haven’t been told and that we have been fighting the same battle since colonisation. Like many other Māori, I grew up colonised and this means as an adult you fumble along, trying to make sense of a world that you only had glimpses of as a child. Sometimes being Māori feels like you’re on the sideline watching and then someone chucks you the ball and you want to play along but you don’t really know the rules.

I wrote The Pōrangi Boy for kids like me who struggle to see themselves in stories. For those who feel like they are on the outside watching, observing, but never quite belonging. I wrote it for people like me who were forced to learn about their own culture through the eyes of the coloniser. I wrote this for people who think Māori activists are pōrangi for fighting for our land back, land that belonged to us in the first place.

*name changed

The Pōrangi Boy, by Shilo Kino (Huia, $25), releases October 23 and can be pre-ordered from Unity Books Wellington and Auckland.