An essay about race, immigration, and KFC by Sri Lankan-born, Hutt Valley-raised novelist Brannavan Gnanalingam.

On our way to New Zealand in 1986, we stopped at Singapore Airport. In this of all places, my dad bumped into his brother, whom he hadn’t seen for years. We were going to a new life in New Zealand. My uncle was going to back to Sri Lanka during its Civil War. It sounds like the start of a movie, except there is no ending that we know of: my uncle was “disappeared”, to use an Argentinian term, and my dad still searches for him. But for me, Sri Lanka was never ever going to be home. I’m a foreigner there.

Dad got a job in Lower Hutt and we became Wellingtonians. It’s quite trendy for lefty liberals to say that Wellington is a “white” city, lacking in diversity. That compared to Auckland or London or some other mythical city, Wellington sells out of sunscreen on the rare occasions we have a proper summer and that ordinarily we look like a National Party caucus photo. To those people, I give my middle finger. First, to call Wellington “white” denies my existence and what I grew up around. It also suggests that the people who say it have spent their time at literary festivals rather than going anywhere near the Hutt.

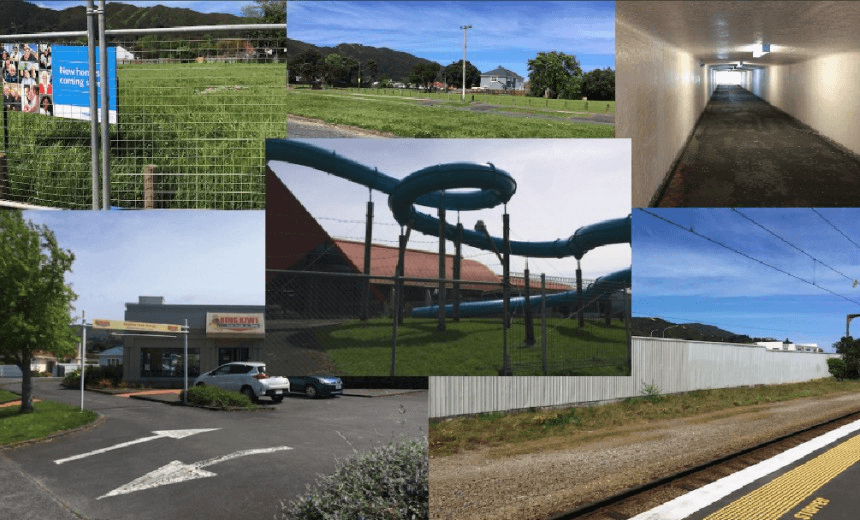

The first meal my family had in New Zealand was at the Avalon KFC. It was probably a big deal for my dad to take us newbies from Sri Lanka via Zimbabwe to a KFC. I kept going back to that KFC. It was the first place I drove to by myself when I got my restricted. My friends were strict Maccas visitors – on account of one of my high school mates being a manager and his ability to obtain 10c discounts on burgers – but I’d always sneak over to Avalon on the way home for that chicken salt.

I have no idea how my first interactions here went; for the first wee while, I would have spoken a hybrid of Tamil and Knight Rider-influenced English. But by 1990 South Asians were common enough in Wellington for the epithet “curry muncher” to be used in my direction. I had no idea what was wrong with curry. I assumed “Aaron” (his real name, who am I kidding?) wasn’t comparing curry to Michelin-starred cuisine though, so I told on him, and he started crying.

I have some idea of how different it was for my parents. My parents spoke to me in Tamil and I always replied back in English. I still do. It was a few years before the opening of Wellington’s first curry restaurant made the front page of the Evening Post. My mum couldn’t find some of the key ingredients for Sri Lankan cooking. There were stories of bemused Kiwis being confronted by exotic produce like eggplants; because they didn’t know what to do with it, they boiled the crap out of it for half an hour before eating. Other immigrants also struggled in that regard: my Italian father-in-law had to go to the chemist to get his olive oil. Probably some hangover from Muldoon’s tariffs.

I grew up in Naenae and went to school in the Hutt. Naenae was a place that had a reputation for infamy and vice – except for its totally awesome ZoomTube – but I never noticed anything unusual growing up. The Naenae Nazi Party at the time was limited to two people, and even they left me alone. The closest thing to a kerfuffle was when my parents’ entire street shut down for a joyous street party when Tonga beat France in the 2011 Rugby World Cup.

Lower Hutt was gloriously multicultural, even in the early 1990s. I had friends from Malaysia, India and Hong Kong. Of course this sounds like “I had Māori friends in primary school,” but one of my friends almost cracked first-grade NRL for the Newcastle Knights (he was from the league stronghold of Wainuiomata) and another friend ended up the top Māori student in New Zealand in my Bursary year. Our teachers taught us te reo and kapa haka – which at the time none of my whitebread Whitby friends had any idea about. Even among my “white” friends, I had friends whose cousins were Gaelic harp champions or whose parents were South African emigres (who strangely returned as soon as apartheid ended). My neighbours were always Māori or Pasifika. Difference was normal.

And growing up, my own difference felt normal. It was simply part of the overall community. Initially, there was Bharatanatyam (South Indian classical dance) and Tamil School classes that my sister and I went to, along with other kids of the first generation. Dipak Patel was a key part of the 1992 Young Guns, and even if his “mystery ball” was the one that spun, at least his skin colour was mine (see kids, that’s why representation matters). Another star in the Hutt Valley Tamil community, Mayu Pasupati, was tipped to go far in cricket, but playing for the Firebirds and taking that catch was as far as his career went. Still, we were in awe of him growing up.

I feel as Wellingtonian as they come. But whenever politicians attack immigrants for self-serving ends every three years, I’m reminded of how shaky my foundations feel. I also get this feeling whenever people ask me where I’m “from”, or concede, “oh, you’re a Kiwi.” There seems to be a positive value judgment in being described as a Kiwi.

Despite feeling like a Kiwi, I always felt like I was hopping between two worlds. When my parents came over, as far as they were concerned, they no longer mattered. Everything was for my sister and me. As a result, I was the dutiful diasporic son. I did well academically, and otherwise, at school and at university. I am now a lawyer at a good law firm. Like many Tamil kids, these were non-negotiables: we were going to go to university and get a professional job. It wasn’t as if I could ever tell my parents, “you know all of those sacrifices you made? To be honest, we just need to seize the means of production.”

On the other hand, I had creative layabout leanings. I wanted to be a musician or a filmmaker initially, but I chose law because it was the longest degree I could think of that didn’t involve cutting up people. I fell into writing through Salient at Victoria University. I have focused on writing to achieve the success of publishing with a Wellington anarchist publisher with a relaxed approach to typos (hey, if it worked for Keri Hulme). My books are undeniably political. I think that’s natural when there are such few POC immigrant voices in New Zealand. Also, I couldn’t simply accept the dominant myths that I saw around me: every interaction appeared foreign and had to be negotiated. I drifted around the world. I lived in Paris. I backpacked in North and West Africa. Central Asia. The Caucasus. The Middle East. South America. I’ve been to nine of MFAT’s current “extreme-risk zones”. My OE was frequently spent trying to convince immigration officials that I was a Kiwi.

I never felt particularly close to my “Tamilness”. I don’t watch Tamil films, go to the Hindu temple, or participate in Tamil events. I love MIA, but I got to her music through Pitchfork. I never supported Sri Lanka in cricket either. That said, I do feel grateful for one cricket performance, when Sri Lanka played New Zealand in an ODI on January 3, 2007. I was at my parents’, and had been planning on going for a run in the firebreak around Epuni. Just before setting off, I saw that the ODI was on free-to-air TV. I stayed behind to watch it. New Zealand was bowled out for 70. I was annoyed that I forewent exercise for such an abject collapse – only to see that Graeme Burton had gone on his killer rampage at the exact firebreak I was heading to. Aside from that, I never really lived and died by what Sri Lankan cricket did. I still feel jealous of my cousins who had close and real connections to their heritage. But I’ve never tried to fix that.

But can foundations ever be stable, despite what the politicians say? I’m not sure I trust my own definition of the Hutt or what is home. This seems to be the immigrant’s curse, particularly those who belong to a diaspora.

While I no longer live in the Hutt, each time I visit I see little cracks at the edifice of what people so definitively consider “home.” Naenae is one of the few affordable suburbs in Wellington, so middle-class families are holding their noses and buying out there. The Housing NZ flats behind our house are now gone. Demolished and sold to developers, they are just bare patches for seagulls and mud to congregate on. Who knows where the former inhabitants have gone. There are dozens of curry restaurants now – jostling among all the other ethnic eateries. The Hutt vege market sells obscure sub-continental vegetables: gottu kola, murungakkai, and pavaakkai, for example. The firebreaks have been replanted with native bush and the native birds are starting afresh. The KFC, my KFC, has disappeared. It’s now a nondescript takeaway. It still has the same fitout, it still sells fast food. But the KFC is down High Street in Hutt City. Hell, the whole city is now no longer called Lower Hutt. It’s as if roots can never really go into the ground. The ground is always being churned up.

Sodden Downstream by Brannavan Gnanalingam (Lawrence and Gibson, $29) – a novel about a Tamil Sri Lankan refugee who comes to the Hutt Valley – is available at Unity Books. Brann is talking at Wellington’s awesome LitCrawl event on November 12 with Eleanor Bishop, Victor Rodger, and Harriet McKnight on “Why I’m Writing What I’m Writing.”