Joy Cowley reveals her enthralling life story, from a difficult childhood, to getting drunk with Roald Dahl, to encountering an Arctic polar bear.

Content warning: contains reference to attempted suicide.

On a dreary Ōtepoti day in June, octogenarian New Zealand children’s book author Joy Cowley takes my cheeks in her hands and narrows her eyes, searching the outline of my face. For nine years Cowley has been losing her sight through macular degeneration, a condition that she accepts will eventually erode her independence, but a fate that hasn’t stopped her writing. “It’s just a different way of living,” Cowley says. “Already there is such a big difference in my sight since the day I came here.”

“Here” is a tidy retirement village tucked away in a small valley just a stone’s throw from Dunedin’s city centre. Never reluctant to start a new chapter, the decision to pack her bags and move south was Cowley’s entirely. After the death of her husband, Terry Coles, in August 2022, Cowley was ready to wave goodbye to Featherston, much to the surprise of her four children (“they are not children now,” says Cowley. “They’ve all got gold cards!”)

Cowley discovered her new home on a summer’s afternoon when a mate took her on a drive. “All the roses were blooming and each house was different and it had such a beautiful atmosphere,” Cowley says. “We went and had afternoon tea and people came in and had a chat and I thought, ‘This is me.’”

Cowley invites me to sit down in her kitchen while she uses a chunky plastic magnifier to help her navigate: the bench is dotted with fresh homemade empanadas she whipped up that morning by feeling her away around; a recipe she remembers from a trip she did backpacking solo around South America after meeting her second husband Malcolm Mason.

We sit down to nibble the flakey treats, and over a hot cup of tea, Joy Cowley tells me her life story.

The early years

Life began in Levin. Cowley was raised by her Scottish father Peter Summers and her mother Cassia Gedge. As the oldest of five, her childhood wasn’t easy. Her mum suffered from depression, which Cowley now suspects was undiagnosed schizophrenia. Peter Summers had a weak heart from several bouts of rheumatic fever and was also deaf. “He was a good dad, he loved us and if he was angry about something we would know why.”

Cowley’s mother, on the other hand, was not so straightforward, and was violent with all of her children. “We didn’t know what was wrong with our mother because she could be so nice one day and the next day she could be hitting us and hitting us. She would say God had told her that we were talking about her on the way home from school. I would immediately agree and tell her a lie to stop her from hitting me. That same woman could be so nice and she would give us a hot cup of cocoa in bed, and she might tell us a bible story, and it was years later that we discovered that she was mentally ill.”

Many years later, a doctor would say to Cowley that he was surprised none of her siblings died from the beatings by their mother they endured.

Cowley plucked chickens at a poultry farm after school to help make money for the family. With their ill health, her parents struggled to make a living, and as the oldest she took on the role of running the home. She could often be found helping her dad with heavy lifting: “ I was a very strong kid. Dad and I built our small house together. We had no money but a kind man gave dad timber and told him that he could pay for it later on.”

Cowley’s dad also indulged and encouraged her intrepid side: he signed a consent form that let her go behind her mother’s back to secretly ride her motorbike to the Palmerston North and Middle Districts Aero Club on weekends to fly Tiger Moths.

That same spirit spurred Cowley to get on the bus from Foxton one day to enrol herself in high school in the city. The teachers knew she couldn’t afford supplies so found her a free secondhand uniform, a blazer and secondhand books. “They were wonderful to show such kindness. I loved that school.” Initially Cowley struggled to read, but soon gravitated to words through a love of story.

In Year 10, Cowley’s family asked her to leave school and start working to help provide for her siblings, but the principal of Palmerston North Girls’ High School persuaded her parents to let her stay. The school organised a local family to provide Cowley with board, and arranged a job for her after school at Palmerston North Daily Times newspaper, where she was in charge of the News for Children page. They ran competitions with prizes to encourage kids to send in their writing.

“With the sort of house we had, which was pretty irregular and sometimes a bit frightening because of my mother, I used to tell my sisters stories,” says Cowley. “We’d all snuggle up in bed and we would actually be strengthening ourselves, because I would tell stories about these wonderful, strong girls who had adventures, and so it was easy to run the children’s page.”

Cowley loved her new “career”, and at the end of 1953, the local paper offered her a cadetship that she was forced to turn down because her mother, much to Cowley’s surprise, had secured her an apprenticeship as a pharmacist in Foxton; a job she initially despised but on reflection says taught her good discipline. “Sometimes when life turns you upside down it is because you need it. I was great with writing stories but I didn’t have any discipline; my life wasn’t structured.”

First marriage, children, and a crisis

At 19, Cowley (then Summers) was working in a chemist shop when she became pregnant, married Ted Cowley and started a family. They had four children, Sharon, Edward, Judith and James, who she cared for all while waking up early and milking the cows on a small dairy farm at Whakarongo where they lived. Money was tight and everything had to stretch so there wasn’t a lot of time to write.

While Cowley loved having a family, her marriage to Ted was an unhappy one. “Ted loved his children, but he didn’t love me. He married me because I was pregnant.” Ted Cowley was planning to study engineering at university and Joy was preparing to hide away in Auckland with an aunt and have her child in secret, when Ted’s mother insisted her son marry Joy or she would disown him.

“So the poor fellow did marry me, and I gave him permission to go out with anybody he wanted. We had four children fairly rapidly in four and a half years, and he was out a lot at night. So that’s when I started writing; after the children were tucked down. Sometimes he wouldn’t even be back in the morning and I’d be up milking the cows. Somehow it worked in a way, until he fell in love with somebody.”

In 1958, Joy began writing to the New Zealand Listener, eager to get one of her stories published in the popular magazine and prove to herself she could be an author. Then Ted asked Joy to move out for six months, vowing to get the affair “out of his system”. Joy packed the family up and rented a flat in Ashurst with their children.

After six months, Ted went down to the school one day and brought the kids back with him to live. Joy went to a lawyer who told her that if she went to court the boys would go to Ted and the girls to her but Joy couldn’t bear the thought of splitting the family. “It was a terrible thing. I thought I could survive it. Ted promised that he and Jenny would bring the children out to see me every weekend, but that wasn’t happening.”

The situation reached a crisis point when Joy, who was desperate for shared parental custody, had planned a special evening with her children that was suddenly derailed by Ted. Just as she’d finished cooking dinner for the children she got a call from Ted saying he was instead taking the kids to see Jenny in a skating show. “I just put the phone down, went into the bedroom, tipped a bottle of Seconal into my hand, put two tablets back in case I needed them, and took all the rest. It was a completely irrational thing to do because I knew that you could die with about seven tablets, and I took about 13. That was the most extraordinary event in my life. The world dissolved.”

Thankfully Cowley’s sister Heather found her unconscious on the floor, called an ambulance and paramedics rushed her to Hospital. “After two weeks, they let me go, and the psychiatrist I had seen sent me a lovely report. He said, ‘No evidence of psychosis, normal reaction to abnormal stress.’”

Her suicide attempt would later be the impetus to open up a retreat in The Marlborough Sounds, free of charge for people suffering but who couldn’t escape their circumstances.

Writing and Roald Dahl

After divorcing Ted, Joy met her second husband, Wellington writer and accountant Malcolm Mason, who she describes as a loving stepfather to her four children. “Malcolm was a lot older than I. He had been a captain in World War II and then a prisoner of war. He was a youthful man, even in his 80s, and he talked about death as the last great adventure.” The two shared many trips together in their 15 years of marriage before Malcolm died in 1985.

Throughout this time, Cowley’s stories began getting traction. After two years of submissions and 40 rejection letters the New Zealand Listener finally published a Joy Cowley story in 1961. And her story The Silk was published in the New York magazine Short Story International which led to Anne Hutchins, the chief editor from Doubleday, picking it up and writing to Cowley to ask if she had a novel.

Cowley didn’t reply for three months until she got a second letter from Hutchins asking the same question. “It was very encouraging so I sat down and wrote what I thought could be the beginning of a novel and sent it to her.” Hutchins’ reply was an advanced royalty and a contract for Cowley’s first and famous novel Nest in a Falling Tree, which paid for help with housework and cooking so she had time to write, a luxury Cowley didn’t take lightly.

Nest in a Falling Tree caught the interest of the internationally acclaimed British writer Roald Dahl, who purchased the film rights and made it into a thriller called Night Digger which starred his wife Patricia Neal as Maura Prince. To this day, Cowley is still perplexed by his generous offer. “He did such a different thing with that book. He could have just written it himself but he paid quite a lot of money for it.”

That deal saw Cowley and her husband Malcolm travel to Great Missenden in North London and visit the Dahls in their home which had a heated swimming pool, hundreds of green and yellow budgies, a fruit-laden orchard and walls of orchids growing against a wall around his writing desk.

She recalls the evening clearly because the couples shared a few drinks. “I had not been used to alcohol, and I got very drunk. I drank them like milkshakes. I wobbled around his swimming pool and fell in.” The night ended with Cowley borrowing Patricia’s clothes to keep dry.

Cowley describes Dahl as “extraordinary and inventive”, but admits she wouldn’t call him a friend because he made her feel a bit uneasy. “He kept in touch, but he was very self absorbed, and there was something about him that was just a little bit … well, if you’ve read his short stories, then you’ll know what I mean.”

In 1971, she released her second novel The Silent One, which followed a deaf boy’s friendship with a threatened turtle. It was inspired by her father’s experience with hearing loss and a letter from a school teacher who wanted a resource for deaf students.

Third husband and the Arohanui Retreat

Roald Dahl’s film deal gave Cowley the financial freedom to move to The Marlborough Sounds, buy a house in Fish Bay and fund a new project, The Arohanui Retreat. Cowley took referrals from Doctors and The Women’s Refuge who suggested people who would like to stay at Arohanui for rest and recovery free of charge. “They would come and stay for a few weeks just to have good food, to swim, to go out on the boat, to catch fish, to let all of their stress go.”

In 1985, Cowley married Terry Coles, a former priest who she absolutely adored. “He phoned me one day and his words were ‘Bugger this, I want to get married’. I waited for him to tell me who he had met when he said, ‘What do you think about that?’ And I realised he meant me!”

The couple initially bonded as friends over their shared faith. “There are two sides to my life. One is the writing and the writing for children and the other is the spiritual side. I’m a Catholic. I’ve done several courses for companioning with people. I don’t use the term spiritual direction. I don’t like that but just companioning people, sitting with them, listening to their story.”

Terry and Cowley shared a full life in the Marlborough Sounds. They hosted people at Arohanui for over two decades, and enjoyed the lifestyle: “There were a lot of fish in the Sounds, but I didn’t take more than I needed … If it was a nice morning, I’d go out and bring back a snapper and wave it in front of Terry’s sleeping face and yell ‘breakfast!’”

Cowley wrote hundreds of imaginative children’s stories during her 20 years in Fish Bay. Mrs Wishy Washy came to her after having a hot bath on a cold wintry morning, and Greedy Cat was a flashback from a childhood friend’s gluttonous feline.

Along came Wendy Pye

Joy Cowley has written more than 1,100 books and sold over 40 million around the world. She credits Wendy Pye and her triumphant educational publishing arm Sunshine Books for her global success.

The Western Australian business woman was managing the publishing side of the NZ News Group in the 80s when she hit a bump in the road: “When she wanted to try and take New Zealand books to a book fair overseas, they refused and she told them they were all dead from the neck up.”

That pitch ruffled a few feathers, particularly in the older, male-dominated workplace who quickly shut her out, marching her out of the building in a brutal and sudden redundancy.

Wendy called Cowley with the news, devastated that she had been sacked after spending 20 years establishing multiple companies. “So I said to Wendy, look, now’s your chance. You could have your own publishing firm.”

Cowley’s instincts were bang on because Pye went on to shake up educational publishing across the world, and in 2024, made NBR’s Rich List, and was awarded a Dame Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for her services to business and education. Thanks to Pye’s efforts, Cowley’s books became popular in the USA and she began visiting schools, reservations, and writing stories across North America for up to three months of the year. Each time she would venture to her happy place, Chautauqua, a writers retreat and camp for the arts in southwestern New York State.

Everywhere Cowley went she would record her interactions with children. Her travels with Story Box and Sunshine Books took her to Singapore, Mainland China, Malaysia, Brunei and remote parts of Alaska, where she saw a polar bear stripping the flesh off the skeleton of a whale. A stay on the Tohono O’odham Reservation in southern Arizona, near the Mexican border, inspired Cowley to write Big Moon Tortilla after she attempted to make tortillas herself (“mine looked like a tennis racquet without with holes in it. All the women laughed at my tortillas and that gave me the idea for the story”). She ended up sending the first two lots of royalties earned from the book to the reservation because she could see they needed the money: “they’d been shunted off their own land and onto desert. They told me that the government had found uranium under the soil.”

Cowley’s aim when she travelled was to build up literacy material for the schools in each of the places she visited. While Cowley loved seeing her books abroad, she didn’t see them as a solution for getting young readers hooked – she knew children needed to see themselves and their culture. She developed a passion for teaching those communities to write their own stories: “I didn’t understand why teachers in Hong Kong were reading to the children about English thatched roofs and boiled eggs and soldiers for breakfast.”

Thousands and thousands of children from the US, Australia, The UK and Aotearoa wrote letters to Cowley who responded to each and every one. Cowley admitted she didn’t always respond to letters from adults, but would always write back to the kids quickly because waiting for anything as a child feels like an eternity.

We break for a cheese roll in the retirement village cafe. Everyone warmly welcomes Cowley, and it’s genuinely a nice place to be. The manager walks over to our table. “I have a big box for you, Joy.”

“Oh yes, I’ve been waiting for this one,” she replies.

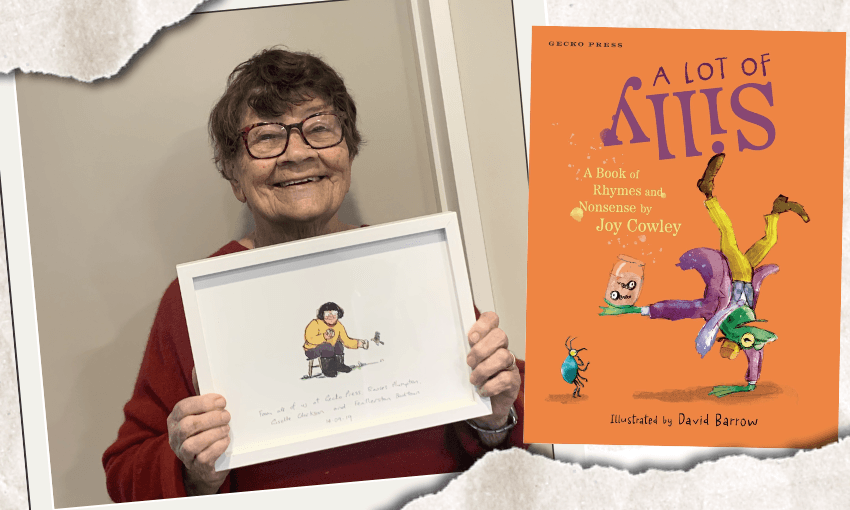

In what feels like divine timing, an enormous pile of bright orange books has arrived from Cowley’s publisher Gecko Press. She grabs a sharp knife and slices through the box without hesitation. It’s like Christmas witnessing Cowley unbox her latest creation. “Well, Isn’t it lovely that this arrived on the day you arrived!” She laughs when she peers at the front cover with her magnifier, delighted that the word “silly” has been printed upside down deliberately. A lot of Silly is a book of rhymes and nonsense, and is a true original, just like Joy.

Joy Cowley sends me away with a technicolour woollen blanket that she’s crocheted herself, the new poem Ballad of the Blind, and a freshly signed copy of A Lot of Silly. Three keepsakes I will treasure, totally emblematic of her.

The Ballad of the Blind by Joy Cowley

Let me sing to you

the ballad of the blind

music as thick as mist

and words growing through it

to open in a new fragrance

I do not have a name for this

but I do know

that the heart

has another way of seeing

A Lot of Silly by Joy Cowley (Gecko Press) is available for pre-order from Unity Books and publishes on 1 October. For those in Ōtepoti, Dunedin there is a Welcome Joy to Dunedin event this Sunday 29 September, details online here.

If you or someone you know is in need of support, get in touch:

TAUTOKO Suicide Crisis Helpline – 0508 828 865

1737 – Need to talk? Free call or text 1737 any time for support from a trained counsellor

Lifeline – 0800 543 354 – Free text 4357 (HELP)

Samaritans – 0800 726 666

Youthline – 0800 376 633, free text 234 or email talk@youthline.co.nz or online chat. Open 24/7.