Growing up Asian in white New Zealand, Joanna Cho tried to find a mirror in books.

I went to a proud, decile 10 high school that had few POC. I prided myself on being part of the “white” group. When my boyfriend in Year 9 broke up with me, because his rugby mates teased him for dating an Asian, I took it on the chin. When I won the English award and there was laughter as I walked on stage, I joined in. Later, in another year, a new English teacher pulled me aside after class. She had read my short story and thought it was lovely, but couldn’t understand the metaphors. But don’t worry, I know English is your second language, she said. I said English is my first language and she said Oh.

I guess we just didn’t know any better. There weren’t many Asian role models available in the western vernacular (and there still aren’t). The only Asian characters on TV were hypersexualised Alex Munday from Charlie’s Angels and oppressed Lane from Gilmore Girls, which reinforced racist stereotypes. Apart from Jackie Chan, for the most part, the only Asian actors on the big screen were secondary and disposable. Music was relegated to candy-coloured K-pop, and we read Memoirs of a Geisha, not knowing it was written by a white, male American. We played “Chinese Whispers” in class and teachers were often heard saying Speak English, you’re in New Zealand now. Our ability to master the language and culture was a proxy for our overall intelligence and worth. I felt small every time I went to a friend’s and was reminded of how different the etiquette of my own home was.

Before taking the publishing course at Whitireia last year, I hadn’t thought much about the near-absence of Asian writers on shelves, nor the lack of reliable representation of Asian characters in books, in Aotearoa. When I learnt about mirror books and window books – those you see yourself in, or that show you a world different to yours – it occurred to me that I could remember reading only two books during my childhood with characters that looked like me in them: Chinese Cinderella by Adeline Yen and The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan – and they’re not even Korean, just Asian.

Kit Lyall, manager of Christchurch’s Scorpio Books, talked to our class about how often you don’t know you’re craving representation until you see it, and then you wonder where it’s been your whole life. They also said, “A lack of diversity not only influences how diverse peoples see themselves, but how we are seen (or not seen) by those of the dominant culture, and the effect of this is far-reaching and insidious, manifesting in spheres beyond bookstores and libraries.” As a queer person, they knew from personal experience.

For our final assignment, a seminar on an industry issue, I researched the lack of Asian writers being published in Aotearoa. I wanted to get an idea of what obstacles are in place for Asian writers here and what’s being done to address the problem. The 2018 Census showed that 15.1% of the population are Asian, but I wasn’t sure that was echoed in the publishing industry.

I emailed six local publishers and five local Asian writers with a bunch of questions, and they all kindly replied with generous insights. The writers I talked to each identified many barriers for Asian writers in Aotearoa – collectively, these include the white literary establishment, being tokenised or seen as a fad, and an overwhelmingly English-only publishing scene featuring exclusivity and nepotism. They also noted the limited number of places one could be published, the lack of money from writing – and therefore difficulty balancing work and writing – and the assumption from publishers that their books aren’t commercial or won’t appeal to a wider audience, which links to an assumption that Asian writers have to write a certain way, or about certain themes.

I wondered if it makes sense to categorise writers by ethnicity, and to this, Gregory Kan said, “On the one hand, it can be great marketing, exposure and visibility. On the other, it can be reductive, tokenising, exploitative, co-opting, etc.” Sharon Lam said, “It does seem quite silly, but still important at the moment. The same way that introducing someone as a “woman _____” now sounds really silly, but was once important to have, to raise their voices and make them noticed by the norm. So once there are more Asian voices in the NZ scene, it will be unnecessary to have such a category.”

I was curious about this because when searching for Asian writers to interview, I realised how easy it is to assume someone’s ethnicity based on their name or looks, and how easy it is to get it wrong. For example, Hanya Yanagihara, author of A Little Life, has a Japanese name but is American. Four years ago American man Michael Derrick Hudson made a lot of people mad because he used the pen name Yi-Fen Chou for a poem. He’d been rejected 40 times with his own name, and a further nine with the pen name. His poem ended up being included in the Best American Poetry anthology of that year. Because they thought he was a Chinese woman (ticking the diversity box), or because the poem – rejected 49 times – was actually good?

As for the publishers, in short, when I asked about Asian writers they all said they’re aware of the lack of representation and think it’s important to have more diversity in the industry. One publisher, Murdoch Stephens of Lawrence and Gibson, cited the content of their publications, in addition to representation: “We are explicitly anti-racist, so we won’t publish books that lean on orientalist, banal or stereotypical representations of Asian people or cultures and we put a lot of emphasis on this in the editing of books.” I’d like to assume all publishers are anti-racist, even if they don’t explicitly say so, but I suppose it can be hard to tell when often the harm is in what can’t be seen in the final book – what tone was policed, which map was censored, who was excluded.

One of the projects I worked on last year was the Whitireia Journal of Nursing, Health and Social Services, and one article I edited had quotes by ESOL students, which had many grammatical errors. We had a team discussion on how heavily their words should be edited, and in the end we made very minor edits because we felt it was more important to respect their individual voices. In publishing, there seems to be a constant tug-of-war between serving the author and serving the reader, but then there also seems to be, in Brannavan Gnanalingam’s words, “a real conservative streak to publishing worldwide about assumed audiences”.

Is this why many publishers are hesitant to publish for and about minority groups without some kind of Creative New Zealand (CNZ) funding (for which there is no specific grant to support Asian writers) – because they’re always looking at who the average reader is, and in Aotearoa that’s a white woman in her 40s who likes Joan’s Picks? What will the future look like if we continue to only make books for that assumed reader? Gnanalingam also said, “There’s no market in NZ for anything, so that kind of means there’s a market for anything. Why should we be limited to poorly ghostwritten rugby autobiographies and Pākehā men alone in a colonially scrubbed-out rural landscape? Bring on books from Asia.”

It seems there’s no publisher in Aotearoa that does what Huia Publishers does, but for Asian writers. The only platforms I know of specifically for Asian writers, apart from newspapers, are Migrant Zine Collective and the online journal, Hainamana, which has not had steady funding since it began in 2016. Amy Weng, editor of Hainamana, and Alison Wong launched a new project in March called Epigraph, funded by Mātātuhi Foundation. This online journal is hosted on Hainamana and features an Asian-New Zealand writer every month.

I’ve been thinking about my role as an editor and as a writer. Last year I learnt more about our country’s history and Māori tikanga and language than ever before. It wasn’t until I took the publishing course that all these arguments about identity, respect, representation and accessibility really hit home. It had to become personal for me to understand – it had to occur in the space of books.

I’ve been thinking of my nieces, who were born in Auckland to Korean parents and speak both English and Korean fluently. Aged three, five and eight, they read books in both languages, but will they continue to have access to books that show girls that look like them, eating 미역국 on birthdays and kowtowing to elders, but also girls that look like them, living a life coloured with more than one culture? I’ve been thinking about my sister who rebelled in her own way by giving her kids Korean names only. How, at seven, I was told to change my name by a teacher because the people at my new school found “Eun Sun” too hard to say. In the playground, kids practised saying “Peter-Piper-picked-a-peck-of-pickled-peppers” super fast…

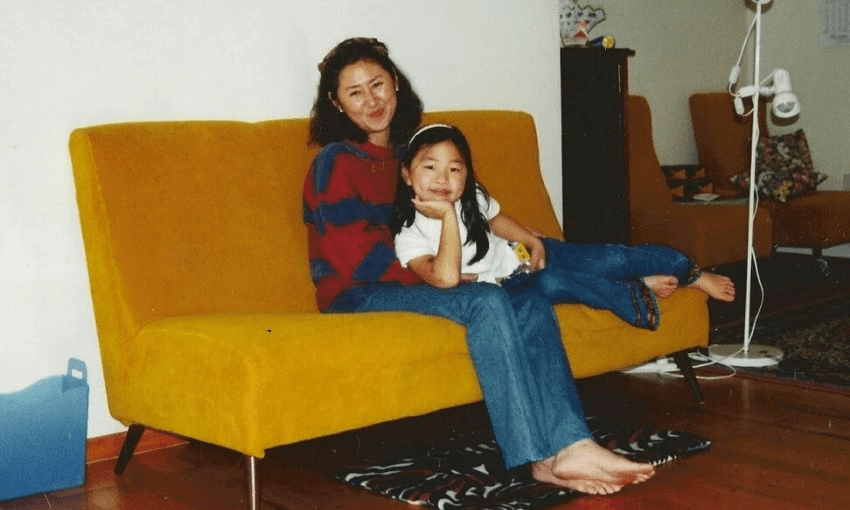

I’ve been thinking about my 엄마, my mother, who moved to Auckland in the early 90s and never learnt to speak English fluently. And myself, born there and raised here, not confident speaking, reading or writing 한글. We face different dilemmas. There aren’t many books by Korean writers translated into English and made available here. 엄마 finds the small selection of books in Korean available at public libraries subpar. She can’t afford to order books from overseas, nor does she know how to use the technologies required to do so. She doesn’t own a debit card. We often enter long pauses of misunderstandings.

Having more books available in translations would help clarify and support cultural differences, as well as help preserve languages and help people from Asian descent here in Aotearoa embrace and better understand their identity. It could also aid in bridging the gap between cultures; basically I think it would lead to better wellbeing all round. Chris Tse agrees: “There’s a big opportunity to do translation ‘exchanges’ with other countries so we can learn more about, and read, each other’s writing. This could apply to contemporary and classic literature.”

I’ve been thinking of street-style fashion shoots taking place in ethnic supermarkets, on 35mm film; an overwhelming presence of Murakami books, with the Submissive Woman trope, the may-or-may-not-be-a-figment-of-man’s-imagination; Korean lettering in music videos. I’ve been remembering Gwen Stefani’s posse of Harajuku girls. 김치 sold as sauerkraut for fourteen bucks a jar. Asian cultures are “edgy” and white boys love necking a shot of soju. Students are flying off to Asia to teach English. We buy large bottles of Tsingtao and drink it in the park, in our vintage clothes. We can do better. People are hungry for something they don’t already know. Let’s teach them new languages and cultures – new characters, histories, philosophies.

I’m writing this in the National Library in Wellington, where there is a display of books by Chinese writers and about Chinese history in Aotearoa. I don’t have many Asian friends. My family live elsewhere. Sometimes I need something to fill the space that feels like homesickness and looks like a glass of milk. I like catching snippets of Korean people’s conversations in 한글, on the streets. I know there are others that feel this way too.

I take breaks. I read Chris Tse’s 2014 poetry collection How to be Dead in a Year of Snakes. It’s 1905, in Wellington. A Pākehā man has declared he is “hunting for a Chinaman”. He shoots a random Chinese man on the street. True story.