If you’re looking for the politician of ‘crusher’ fame, you won’t find her here, writes Toby Manhire.

In her new book Pull No Punches, Judith Collins pulls her punches. Just when you think she’s about to call out the politician who left secret documents on their desk for journalists, she stops short. She denounces two union men turned Labour MPs who betrayed the workers and drove her into the arms of National, but she won’t name them. Nor will she name the MP who sought to stop her seeking a nomination in 2002. In fact, with very few exceptions, she barely attempts to lay a finger on anyone.

The first chapter describes Collins’ first involvement with the National Party in 1999. My bet is an editor hoisted it forward from the middle of the book to bust the chronology and spark up the top with politics. It doesn’t work. The political foundation story? “The National Party’s principles of economic and personal freedom coincided with mine so I joined the party in Epsom,” she says, as if explaining the thinking behind a stationery order.

The very next paragraph, we get a sentence so contorted it may be a cry for help. “By now, having ejected Prime Minister Jim Bolger for New Zealand’s first female PM, Jenny Shipley, and losing the support of Winston Peters’ New Zealand First Party on the way but keeping some of Peters’ former MPs as ministers and trying to keep on board the vote of the ex-Alliance MP Alamein Kopu, quite a few New Zealanders seemed to think that National was toast.”

This is on the second page of Chapter One.

The chapters that follow recount a Waikato childhood. The youngest of six to devoted parents. One sister had died as a baby. They grew up on a family farm, making ends meet through hard work. It sounds like the kind of childhood that might make a fascinating story. But it’s told less as a story and more as a list of events. The memoir as a whole reads like it was made by going through a crate of old clippings and dutifully, impassively cataloguing them.

Rarely does it dwell to smell the flowers. When Judith’s father disapproves, racistly, of her engagement to a Samoan fiancé, we are told it is “not a happy situation”, but not how it feels. To deal with the problem of “how we could get married with half the family onside and the other half not”, the couple decide to get hitched in Hong Kong. What a yarn this will be. It’s dealt with in a cursory, short paragraph, though we’re assured it “was really quite romantic” and that the shops were open late.

At times you feel you’re holding the book up; as if it’s got someplace else to be. And then all of a sudden it does want to linger, such as for one unbroken page-and-a-half long paragraph on parliamentary standing orders.

There is no real insight into the thinking behind the ideas that Collins says she loves, the ideas which landed her in the National Party. For a politician of such clear and palpable conviction, there is barely any exploring of what underpins those convictions. The first mention of Robert Muldoon, the towering National Party figure of Collins’ formative years, is on page 280. The book is 286 pages long.

It’s not that it’s without bursts of political theory. In a chapter about the Key opposition, Collins invokes Margaret Thatcher as proof that pandering to an imagined “centre vote” is a bad idea. “The advice about sitting in the centre is too often used as an excuse to do nothing, stand for nothing and, consequently, not make a difference. More voters need a reason to vote for us, not against us. Power is fleeting and it needs to be used to make a positive difference.”

Collins later name-checks Jeremy Corbyn, now former leader of the British Labour Party. Whatever you make of his politics, she says, you can’t but love his conviction. It’s an argument she also made in The Spinoff (the all-star lineup also included Jacinda Ardern and Grant Robertson) in 2015.

“No matter how deluded and economically illiterate Jeremy Corbyn might seem to any centre-right voter, at least he stands for something. You know what you’re getting,” she wrote.

“At its best, politics is the contest of ideas. It shouldn’t be about playing the game. It shouldn’t be about doing anything to win. It’s only by galvanising the base, by giving people a reason to care, that those more centrist will give the party a chance. If a party’s base doesn’t see why they’re bothering, then why should anyone else. No matter what side of politics people are, it’s always easiest to sell policies that you believe in.”

Collins’ best route to the National leadership always looked like proving an antithesis to Key. If his attraction to the centre, his mostly agnostic ideology, his incrementalism, were to see the base energy fizzle out, Collins would be waiting. A party approaching ennui would look for steel, for decisiveness, for a breath – no, a gust – of fresh air.

In its final third, Pull No Punches at last fires up the engines. The protracted and heated conflict with Ian Binnie, the Canadian judge commissioned to assess David Bain’s claim for compensation, is chronicled, play by play, and it’s hard to avoid concluding that he (Binnie) was a bit of a dick.

Then comes the part of the book that made the headlines over the weekend. Collins is clearly still enraged with John Key over her annus horribilis, 2014. It saw her traduced, by her account, over the Oravida scandal. Key had failed to recall a conversation in which she alerted him in advance to a dinner attended by company directors and Chinese government officials in China. After accusations of a conflict of interest – her husband was a director of the company – Key instructed her to apologise.

Next, the fallout from the Dirty Politics affair. An email written by the disgraced Whaleoil blogger Cameron Slater had appeared, in which he alleged she was “gunning” for the former boss of the Serious Fraud boss, Adam Feeley. An inquiry later found that allegation to be false, but not before Key had withdrawn her ministerial warrants and, most hurtfully of all, taken away her “honourable” title. This was, as the chapter heading says, “the worst of times”.

Collins’ case is persuasively made in these chapters precisely because they’re delivered very plainly. There is no hyperbole. Nothing histrionic. It’s selective, of course. Collins brushes off her role in Nicky Hager’s Dirty Politics book, for example, as a bit part, without so much as a mention of tip lines and retribution. But that’s unremarkable for a political biography. What is missing is the detail. The characters. The scenes. It’s not just that there’s no scuttlebutt, and hardly a note of mischief. There’s barely any anecdote at all.

Be fair. There are some delicious nuggets. Judith’s father teaching her never to run from a bull in a paddock. The early ambition to become an All Black. She never believed in Santa. Her favourite story book was Pollyanna. She says John Key told her he was quitting because “he realised that he would never be able to deal with Winston Peters after the 2017 election”. Wait, there’s a news line, you think: tell us more! But that’s it. The train has left the station. All the times Collins threw her hat in the ring for the leadership are recounted, but there is no colour, juice or venom in the telling. It is not so much punchy as perfunctory.

Collins pulls her punches. And she disavows, too – or subverts, to put it more generously – the idea of the book’s subtitle, “Memoir of a political survivor”. In assessing political culture, and alluding to Key’s description of her as the last survivor on the island, she writes: “Is this really Survivor? To me, this is a troubling concept, that the ‘winner’ is the one who survives everything else. Is that really why people get elected to parliament? It’s not why I came to parliament.”

This comes in the final chapter, “Moving forward”, in which Collins at last goes into analytical mode. She critiques the “toxic work environment” of parliament – “similar to what I imagine a 1920s boys’ boarding school to have been”. She discusses MMP and why National “need friends” under the system. She points to what she considers to be Jacinda Ardern’s weaknesses, and how National could win.

For the first time, really, there are signs of the Collins of the public spotlight – sharp mind, silver tongue, sparkle in the eye. But if the book was anticipated as something that might cause friction in the National Party, or at least a coded pitch to lead it, there’s not a lot to worry about. “It has been mildly amusing to read the somewhat premature reviews of what is in this book by those who have never read it,” she writes at the outset. But: “This is a positive book.”

Positive, yes, I suppose. It is also so unthrilling that it is hard to see as some clever plank in a leadership bid. But maybe that’s the brilliant plan. Pugilism is so passé. Bring on Judithmania 2023: relentlessly positive edition.

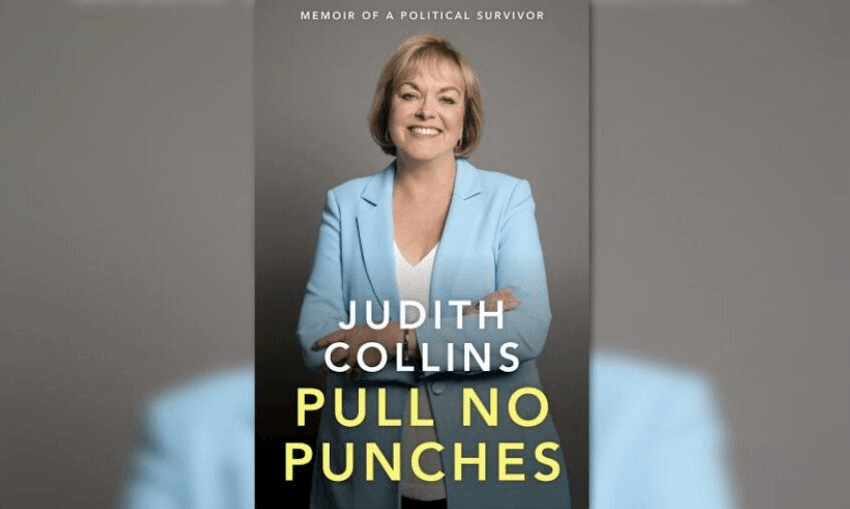

Pull No Punches by Judith Collins (Allen & Unwin NZ, $37) is available from Wednesday July 1 at Unity Books.