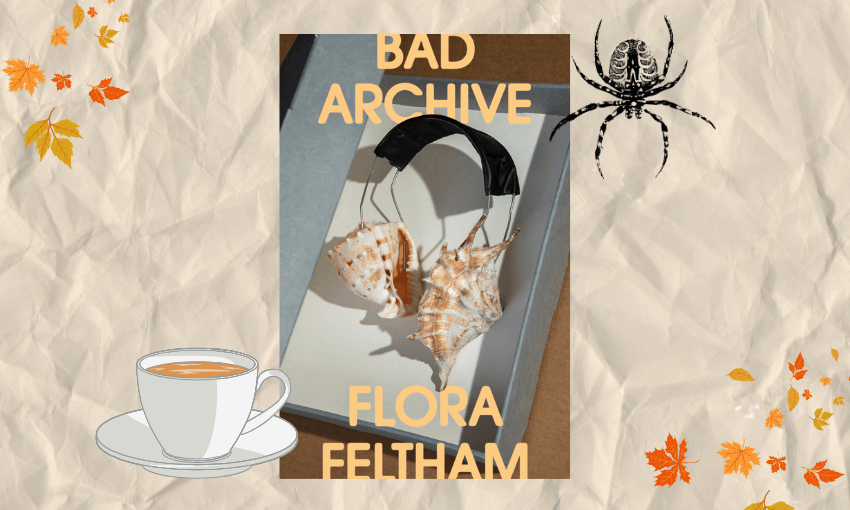

An essay from Flora Feltham’s debut collection – The Spinoff readers’ favourite nonfiction book of 2024, now longlisted in the General Nonfiction category at this year’s Ockham NZ Book Awards.

Ah, I think, so this is autumn: the season when spiders come inside. Outside, a cold weeknight drapes itself over the suburbs, and in other people’s houses I assume time is passing as it should, with gym clothes and leftovers and scrolling. But the spider and I stand still, together outside time. She’d emerged into my peripheral vision as I stepped from the shower, and scurried into the space where my husband removed the bathtub. I peer into the corner from a safe distance and wrap the towel tighter around me. Water begins to pool on the floor at my feet. I eyeball the spider. The spider doesn’t move. Evening continues.

When my mother still rescued me from spiders, she could scoop them up with her bare hands. I remember those bitten nails and her freckled forearms. Don’t worry, she’d say to me, laying her hand on the floor or in the empty tub, they’re more scared of you than you are of them, and then, to the spider, who by now would be stepping gingerly onto her palm, Come on, that’s it. She’d smile back at me. Can you open the window for me please, doll? And I would fling the window open and retreat. My mother would lean out and place the spider onto a plant. There you are.

Tonight her voice still wafts through my brain, like a draught that whispers It’s more scared of you, and for a little moment I can see myself as the spider might. I am large, I am clumsy. I have so few legs. My mother’s voice will always arrive in my mind, usually a quick second after my own, because she was the kind of mother who talked to her children constantly, quietly narrating the world to me, and shaping it like someone kneading dough. She seldom talked down to us.

Like, her rule was: if you want to play sport, honey, you’ll need to ask your father to drive you. Saturday mornings were for dozing in bed or drinking bottomless cups of milky tea and reading. She read dense, philosophical novels by Iris Murdoch and Elias Canetti. There, her thoughts could splash in a pool that lay out of reach on regular days, while she taught small children how to wash their hands and played nursery rhymes on the piano.

You see, when she met my father, my mother was tiny and boyish and cute, an Ethics 101 tutor in Dunedin, all high-waisted corduroys and a shaggy haircut. She wielded her mind like a paring knife. Principled and exact. She used phrases like ‘subordinate clause’ and ‘sufficient conditions’ with ease. Eventually, she was dragged kicking and screaming (her words) to Wellington. After she got pregnant with my older brother, her PhD withered and fell away.

Not a rule but a request, spoken gently, crouched down at child height, as she buttoned up my padded jacket against the wind: “Could you call me Vicky, please?” She explained, standing right there on the path, that ‘mum’ was a word people whined, a word screeched through the house into the kitchen. It was a word that engulfed women. I nodded solemnly. Also, I liked using her name and said it before all my questions, certain my mother had all the answers. Vicky, could I please have a biscuit? Vicky, what’s that tree?

Once, on the way to swimming, I asked her, “Vicky, what were you like when you were young?”

She didn’t take her eyes off the road. “I don’t think I was half as sweet as you, my beloved. I had to leave David Washburn’s 21st because I threw all the empty champagne glasses into the fireplace.”

Quiet beside her in the car and now lost for words, I couldn’t imagine this version of her. I still can’t. My five-foot-nothing mother, who’s always trying to convince people to come aqua-jogging and who sends me photos of her cherry blossom tree. She rings her best friend’s mum twice a week, to pass on news and hear what happened on Shortland Street. My mother’s friend has been sick for months and can’t face explaining – yet again – to his mum that he needs radiotherapy. But someone needs to remind Elaine when she forgets, to gently clarify what’s going on.

Every day after her four kids went to school my mother disappeared into her writing room and wrote short stories. She emerged each afternoon, back into the clamour of family life, to tie herself to the kitchen and cook. Someone always whined Viiiicky I’m hungry, when’s dinner? And, somehow, still, every single evening after the dishes and baths and bedtime negotiations were done, she found time to read me books. One year we read all the Narnia stories in a row — except The Last Battle. She had her reasons. Sitting on my bed she said, “Love, pay no mind to that story. Can you see how it’s not ethical? C. S. Lewis kills off Susan for liking boys and wearing lipstick.”

Once, driving me to a high-school dance, she said, “Flordor, I don’t care who you like or how much, but make sure you wait until university to have sex. Your clitoris will have a much better time.” I blushed from the passenger seat. I also remember her using a different word, one that also begins with a c. She isn’t even sure this conversation ever happened. She might be right, but I still like to think of my mother as the kind of woman who can say ‘cunt’ with tenderness and care.

One winter morning, I rang my mother from my university hostel in Dunedin, homesick after only a few months living in her hometown, dumbfounded by first-year epistemology.

“I can’t do it,” I sobbed. “I just can’t. I don’t understand anything. Vicky, what does ‘synthetic a priori’ even mean?” I was crouched on the floor of the phone cubby, and the other kids in the common room could probably hear me wailing. “I hate Kant, and I’m so uncool here, I don’t have any friends.”

“Slow down,” my mother said. “Start at the beginning. What’s this about Kant?” She sipped her milky tea. “He’s talking about different kinds of truth, my angel, and the way you acquire them. He’s asking, is it reason or experience?”

I slumped back against the wall and relaxed, saved once again. Maybe I didn’t hate Kant. These philosophers, they’re lucky we have mothers.

It somehow came up years later, too, when I was an adult with a bathroom and weeknights and dishes of my own, that my mother had always been scared of spiders. It took all her willpower to touch them and drop them outside.

I gawked at her. “But you never said anything.”

She shrugged. “You were scared, and someone had to do it.”

*

The water keeps pooling and my big autumn spider heads for the door, running in the way that only something with eight legs can. I lunge into her path and trap her under the empty toothbrush glass.

“Oof, sorry,” I say, “I’ll get you out of here in a minute.”

I’m less gracious than my mother, as I address this creature I’m about to bundle outside. I leave the spider there for a minute and ferret out a piece of paper. I also need to put some clothes on because the April evening is getting cold and I haven’t lit the fire yet. I decide to place the spider by the vine near the front door, something sturdy enough to hold her weight.

As I usher her out into the night, I think, Ah, so this is what it means to mother myself.

Bad Archive by Flora Feltham (Te Herenga Waka University Press, $35) is available from Unity Books.