Wanna run with the fast crew? Rebecca Stevenson takes a look at Deloitte’s Fast50 index to see how quickly Kiwi companies’ revenue is growing.

To take a spot among the fastest growing companies in the country in 2017 businesses had to book revenue growth of 180% over three years. But are Kiwi companies growing faster than ever before?

Last night Deloitte announced its annual Fast50 winners. The awards recognise high growth companies in New Zealand based on revenue, and provide an interesting insight into how quickly Kiwi companies have been growing since the professional services firm started them in 2001.

In 2016 to make the top 50 companies needed revenue growth of 225%, and in 2015 the threshold for inclusion was 194%. Compare this with the early days of the Deloitte index and its clear to see there’s been a lift – in 2002 the threshold was 91% revenue growth across three years, in 2003 it was 132% and in 2001 110%.

The top ten, however, is next level growth. Deloitte’s Matt Huntingdon says to be in this category companies needed growth in revenue of 445%. Wowsers. Last year the target was even higher, at 508% and in 2015 it was still a stonking 432%. But unlike the full index, the growth in revenue for the top ten has always been high; in 2010 it was around 500%, Huntingdon says.

Note: we haven’t looked at averages here, because they can be dragged about by outlier results, like Powershop’s outrageous 5280% revenue growth in the 2011 index. But Huntingdon says they haven’t changed much over more recent years at about 400%, and if you go back to 2011 it was about 300%. Another note: to be included companies have to have minimum revenue of $500,000 annually.

So what has this growth meant for the rest of us? Over the last three years Deloitte Fast50 winners have pumped $430 million into the New Zealand economy and created 1609 new jobs, Huntingdon says.

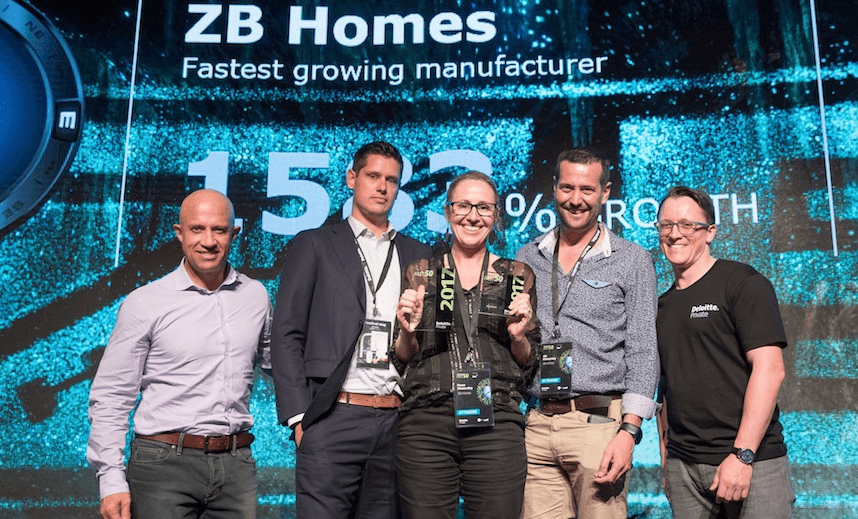

The top award went to construction company ZB Homes, with growth in revenue of a whopping 1585% over the last three years. Also in the top ten were education company Crimson Education which helps students get into Ivy League colleges, and another construction business – Carus Group.

Fintech solutions featured heavily in the technology space, with online lender Moola coming in with the second-fastest growing revenue with growth of 1013% over the last three years (and was the top tech company on the list) – but it copped a bit of backlash on social media for its interest rates. Similarly, church tithing payment company Pushpay came in at number four with 914% growth in revenue over the past three years (Pushpay topped the index in 2016).

About half of the 50 are technology companies, in that they are either in the software industry, or are making apps, or use technology to provide services, Huntingdon says. The rest are a “hodge podge”. He says the key takeaway from the range of companies on the list is this; it’s all about execution and finding that niche.

And how big are these fast growers? This year seven of the 50 companies had an annual turnover of $20 million or more, 18 had turnover of between $5-$20m, and 25 annual turnover under $5m.

For the first time Deloitte awarded a Master of Growth category, with Xero taking it out with 657% revenue growth, hot on the heels of its result and announcement it was leaving the NZX behind to chase foreign investor cash. Social enterprises Eat my Lunch and Organic Initiative were also recognised in the Rising Star category.

rebecca@thespinoff.co.nz bex_stevenson

The Spinoff’s business content is brought to you by our friends at Kiwibank. Kiwibank backs small to medium businesses, social enterprises and Kiwis who innovate to make good things happen.

Check out how Kiwibank can help your business take the next step.