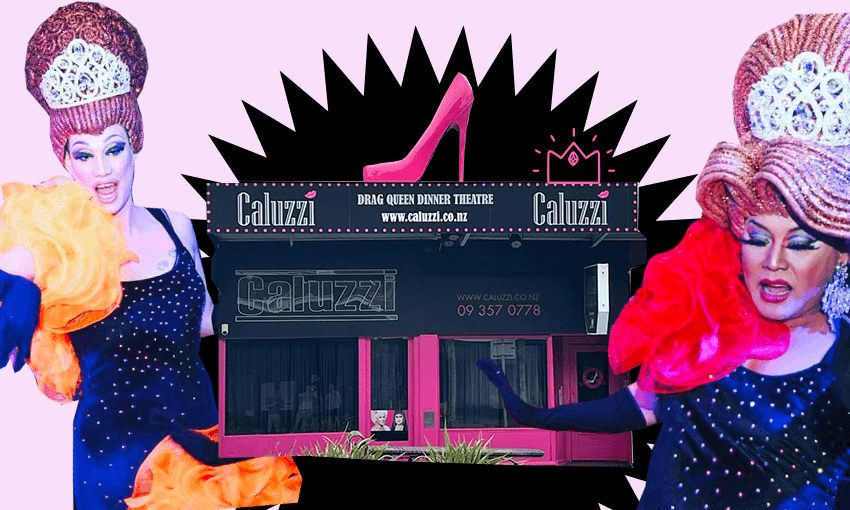

From lunchtime cafe to dinner shows to drag cabaret excellence, Sam Brooks writes on the 26 year history of K’Rd’s genuinely iconic drag restaurant.

If you’re walking down Karangahape Rd on a Friday night, after passing Merge Cafe but before the Thirsty Dog, you might see a drag queen dancing on a bench, lip-syncing to apparent silence. Walk past her and you’ll see through a large, roof-to-floor glass window into Caluzzi restaurant, stuffed full to the gills, cheering and screaming for her while a familiar pop hit plays.

Caluzzi Drag Cabaret, Caluzzi if you’re nasty, turns 26 this year. As the gentrification of K’ Rd continues on, it remains one of the street’s most enduring icons. The restaurant, open for group bookings every Friday and Saturday night, brings together two of life’s greatest pleasures: dinner and drag.

Twice a week, the restaurant takes in 60 people, entertains the socks off them, and pours them back out onto K’ Rd, smiling, with a bunch of blurry photos on their phones to show for the experience. It’s a well-oiled machine at this point.

But well-oiled machines don’t get that way without a little bit of elbow-grease, and in this case, a little foundation and hairspray as well.

The Caluzzi story starts in 1998, when it was just another cafe on K’ Rd. Philippa Burgess owned it at the time, and transformed from a place serving classic ‘90s breakfast and lunch fare – think chicken and cranberry pressed paninis – into an evening dining destination. Before the dinner show was even a twinkle in Burgess’s eye the restaurant was already part of K’ Rd’s queer community, with now-legendary queens Felicia Porget and Courtney Cartier working in the kitchen and as a server respectively. (Both queens are memorialised in the opening of Caluzzi’s current show, and a painting of Cartier hangs in the restaurant.)

The queens would often get ready upstairs after a shift for a night out on the town – full hair, dress and makeup. One night, the story goes, the diners saw the two towering drag queens making their way between the tables, and demanded they put on a show there and then. One show turned into many.

While Porget and Cartier only did their new “drag service” a few nights a week, Caluzzi got busier and busier. By the early 2000s, the lunch service had been dropped entirely and Caluzzi as we know it now was born. A regular show was introduced: punters would get a meal, delivered by drag queens, who performed numbers between courses. Dinner theatre? Not even close, this would be dinner drag.

Campbell Orr was working at another K’ Rd bar at the time, but would pick up shifts at Caluzzi when they were short-staffed. “By the time I got there it was already well entrenched in the community – the local drag queens, the LGBT community,” he says. “It was very much a place that was open and welcome to everybody.”

In 2003, Caluzzi made headlines when founding queen Felisha defected to a drag bar just 100 metres down the road called Finale, founded by Arlana Delamere, daughter of politician Tuariki Delamere. Felisha took four queens with her, leading Caluzzi’s then owner Paul Oatham to exclaim that “someone stole my drag queens”. (Finale closed in 2012, becoming Encore Cabaret.)

Two years later, Orr bought the business from Oatham. Orr focused on making Caluzzi a commercial enterprise: more corporate groups, more birthdays, more hen’s parties. It was then that being a “Caluzzi girl” also became a status symbol: it meant that a queen was part of the family.

Former Caluzzi girl Taro Patch remembers her first night in the restaurant, a try-out for Orr, as an awful experience – her outfit reveal didn’t work at all. But Orr saw something in her, and called her back in a few weeks later. Now she was part of the sisterhood. “Caluzzi was very much the epitome of the drag scene at that stage,” Taro says. “If you were a Caluzzi girl, you were somebody.”

Orr was always on the look-out for three skills, Taro says. First was a good look, standard. The ability to perform, also par for course. Thirdly, and most importantly, was personality, the ability to banter with the punters and make them laugh.

“You had to be able to talk to anybody, from a very drunk bridesmaid, to a 65 year old man having his retirement,” she says. “We even used to have grannies that’d come up from Invercargill once a year, all in their 70s. So we had to know how to talk to all those people, get them to enjoy themselves, even the ones that were just there for a work do.”

With that success came a tension familiar to any queer business, between commercial aspirations and community responsibilities. “We were getting different sorts of people coming through, a lot more of the straight community,” Orr says. “They would come to experience this world of drag, this world of entertainment and fun. So the shows had to be on par with everything else.

“It’s hard to maintain what a place like that is, and what it means to the community to keep it going. But you also realise you’ve got to run a business, and to run a business you’ve got to make money.”

In the early days, Caluzzi catered to the furthest reaches of the LGBT+ community, including the fetish crowd, but Orr eventually pulled back on the more extreme aspects of the show. “We had to keep it a little bit corporate in some respect to provide a service that people are prepared to pay money for.”

After owning the place for over a decade, Orr sold up in 2014. “I was tired of working the long days and late flights on a regular basis, and I wanted to get my weekends back. It’s the nature of hospitality.”

The new owners? Nick Nash and Nick Kennedy-Hall. Or as they’re better known, Kita Mean and Anita Wigl’it.

Kita and Anita, both Caluzzi girls themselves, heard murmurings that Orr wanted to sell the business and jumped in straight away. The pair were, and remain, best friends, regularly performing together at Family Bar and hosting Drag Wars, a popular lip-sync competition. “We said we’ll pay whatever, this place should be ours, we’ll take it,” Anita recalls.

In the eight years since the duo bought Caluzzi, drag culture has changed. RuPaul’s Drag Race has taken the form from the clubs into the mainstream – Anita notes that rostering at the bar now can be tricky due to the regularity with which their 12 queens are booked for lucrative corporate gigs – and a lot of the stigma around drag has dissipated. A night out watching drag queens isn’t seen as a cheeky novelty, but as classy, commercial entertainment.

“We improved the experience for everybody, “Anita says, adding that she likes to use the legendary Moulin Rouge cabaret as a yardstick for quality “Would the Moulin Rouge have a dirty mirror? No they wouldn’t!”

The venue recently started doing drag brunch – a popular event overseas that is exactly what it sounds like – and Anita has hinted at a possible Christchurch expansion of the business. But her biggest dream? A hose-pipe above the street-facing window so they can perform ‘It’s Raining Men’ as the good lord intended it.

Despite the upgrades, the plans for the future, and the expansion of the business – the pair are also behind the popular Phoenix Cabaret further down the road – Caluzzi’s focus remains the drag performance itself. “It’s the most professional unprofessional show, you’ve ever seen!” Anita exclaims, tongue firmly in cheek.

She undersells it.

When we get to Caluzzi it’s a little past 7pm. We’re greeted by Miss Kerry Berry at the door and seated at the bar. Miss Ling Ling, a Caluzzi veteran, and Miss Geena are the other queens on duty – they’re one queen down, but you couldn’t tell. The groups in the room tonight include a work do for an insurance company, a few birthday parties, and what appears to be a celebration of a divorce. A diverse crowd, to be sure.

Before we even get drinks, we’re greeted personally by all three queens. Their patter is what you expect from drag queens – a bit silly, a bit raunchy – but also personable. The 60-seater venue is completely full, but it doesn’t feel like the two of us get any less attention than the big groups ordering wine by the bottle or shots by the bucket (the drinks menu has an enviably long shot list, many of them named after famous Caluzzi girls).

At 7.30, the first food comes out: garlic bread. My plus one checks with Miss Geena that it’s vegan, and is assured that it is. Robert Erasmus, Caluzzi’s chef, recently overhauled the menu, telling me he wanted to make sure the set menu could still cater to different dietary requirements, be they vegetarian, vegan, dairy free or gluten free. The idea being that since the restaurant is close to Ponsonby, the menu should be close too.

As we wait for the show to begin, we marvel at how seasoned and honed the queens are. Caluzzi is not a massive venue, and the queens are navigating it in high heels, full makeup and wigs, taking orders on notepads smaller than their hands. Their smiles never leave their faces, and every sentence comes with a wicked pun as a chaser. They’re every bit the “professional unprofessionals” that Anita promised.

Around 8pm comes the opening number – here’s when you might walk past the venue and see a queen lip-syncing on a bench in silence, while a bar full of 60 people goes off through the window – and Miss Geena grabs the mic to start MCing. She’s a House of Drag alum and K’ Rd mainstay, but I’ve never seen her like this. She runs through the menu (we can have our steaks “medium, rare, medium in your rare”), the house rules (don’t be dicks, also don’t sit on tables, dicks) and what to expect from the evening (songs, songs, songs). She even throws in a few unpublishable jokes that you probably wouldn’t hear from the maitre’d at The Grove, and more’s the pity.

Our starter – a shockingly good pumpkin soup – passes with no drama or spillage. After that is Caluzzi’s coup de grace marketing move: photos. Groups are called out to the benches to take snaps with the queens, later uploaded to Facebook to be shared among the communities and groups whence these work dos, birthday parties and divorce celebrations came.

Then comes the dance competition, which should be the most mortifying part of the night but somehow isn’t. Dancing to ‘YMCA’ loosens everybody up just that little bit more, but while the audience gets more goofy and up for anything, the queens remain strictly professional – eyes looking for tables to clear, glasses to charge, and any sign of someone not having a good time.

The main course is served just before 9 – I go with the roast chicken breast on mash – and then there’s the main meat of the experience, so to speak. The queens on staff do individual lip-syncs – Miss Geena to a Lady Gaga medley (the K’ Rd bench, designed by Peter Lange and apparently named Chaise Lange, more than earns its council dollars here), Miss Kerry Berry to Cher’s ‘Strong Enough’, and Ling Ling to Jessie J’s ‘Flashlight’ – all of which bring the house down.

By the time we leave the restaurant, it’s just after 10. The three hours of service have passed quicker than I could have imagined. It’s been an extraordinarily fun evening, largely because everybody was facing the same emotional direction: here to have a good time, eat good food, drink good booze, and see great queens.

Caluzzi’s presence on K’ Rd is more than just physical, it has a symbolic weight too. The street has long been a safe space for the queer community, but it’s also a space for the queer community to intersect with the straight one, for bridges to be cautiously built and friendships made. Caluzzi is one of the only places in the country where an entirely queer cast performs for almost entirely straight audiences. It’s become a sort of window for the straights to see what the gays are up to, as Anita puts it.

It’s an intersection that could be fraught, but that is rarely the case, Anita says. Most of those who come to the restaurant are open to the experience, even if they aren’t always sure what they’re getting themselves into. “At the end of the show, it’s so good to talk to the nervous ones, who were so worried to be picked on, and see how much fun they had.”

She’s especially struck by the straight men who have their minds changed about drag. “They just realise that I’m a man in a dress who has the same sense of dirty humour that they have. We actually have a lot more in common than they thought, the gender and gayness doesn’t matter.”

Taro, the former Caluzzi girl, recalls similar experiences with straight couples: the men would stay as far away from the queens as possible, trying to avoid any sort of interaction. “By the end of the night, when they realised we weren’t trying to get into their pants, they realised it was all just for fun,” she says. “Caluzzi had a way of breaking a lot of the perceptions, particularly of cis white males, as to what a drag queen was, and as to what people from the queer community were like.

“Yes, we’d flirt with you. Yes, we’d have fun with you. But we were there to entertain you, make sure you had a brilliant night, and forget your trouble for a couple of hours.”

It’s always been important for the space to maintain its family feeling. Erasmus, the chef, helps out with a loose pin there or a stray lash there, and keeps the kitchen a safe space for the queens. “They come in, take a breath, take off their heels, and go back out again,” he says. “That doesn’t happen everywhere.”

Those drag queens who are front and centre, though, are what make Caluzzi what it is. “Our focus was always that we’re here, they’re drag queens, we’re providing a safe space for some fun,” Orr says, of his time at the helm. “If along the way we educated some people, then great. But without the drag queens, there’s nothing.”

As I leave Caluzzi, it’s the queens that remain in my memory. Miss Geena delivering sewer filth jokes as sweetly as a Julie Andrews character. Miss Kerry Berry constantly checking in on my friend and me, despite the 58 other people in the room who also required attention. Miss Ling Ling, taking down an order with the seriousness of a mess hall cook, then looking up to us with a smile and taking our next order.

In the corner of the restaurant, the portrait of the late Courtney Cartier looked on. I’m sure she’d be damn proud.