The video, shot from a car that blocked the PM’s van, gained loads of attention online, but how does its creator feel days later? Dylan Reeve finds out for IRL.

On Saturday, January 21, the prime minister travelled to Northland to participate in the Waitangi National Trust Board’s virtual Waitangi Day pre-recording (the trust had opted in late 2021 to make this year’s event virtual). But according to popular claims on conspiracy theory Telegram and Facebook groups, the real reason was more suspicious: the prime minister was, they suggest, secretly conspiring to complete a vital ceremony ahead of time to avoid massive protests.

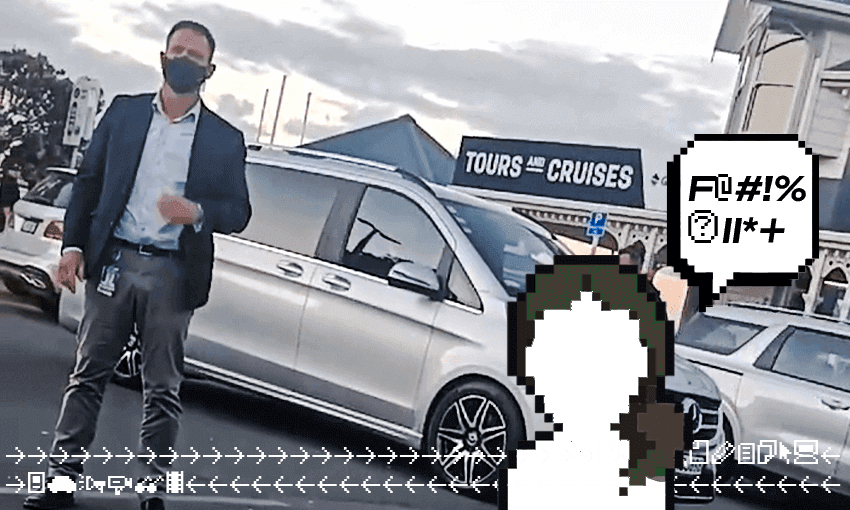

As with any public appearance in recent months, the PM’s visit was met with loud protests, mostly focused on the government response to Covid, specifically vaccinations and the various restrictions connected with vaccination status. What was more unusual on this occasion was a video that began circulating the following day. Filmed from the passenger seat, the video shows a car attempting to block the PM’s van as it exits a parking area in Paihia. The van’s driver is forced to take evasive action, driving over the curb and across a footpath to get past.

The story made headlines across New Zealand media, and was the subject of questions put to the prime minister during a post-cabinet press conference on Tuesday. “At no point was I worried about my safety or the safety of anyone who was with me,” Ardern said at that time.

Lolly*, a Northland mum in her mid-20s, was a passenger in the car that blocked the PM’s vehicle and shot the now-viral videos of the incident. She was also the voice heard yelling abuse out the open window towards the van. “My mouth went a little crazy in the video,” she admitted sheepishly when I cold-called her to ask about what thousands had watched.

“There’s Jacinda in her fucking bullet-proof van, hiding from the public, we’re fucking chasing her round Paihia,” Lolly can be heard saying in one of the videos.

Lolly’s concern was mainly around the impact of vaccination requirements, she says. “Ever since everything has come into play, really, it’s just divided everybody and everybody looks at each other differently now. Like, I don’t know about everywhere else, but in [town] if you’re not vaccinated you’re treated so differently.”

Personally, Lolly has got “got nothing against” the Covid vaccine. “My best friend and everyone I live with is fully vaxxed,” she told me, adding that she was planning to get vaccinated after completing her pregnancy. (It should be noted here that there is ample evidence of the safety of the Pfizer vaccination at any stage of pregnancy, and pregnant people are at greater risk of serious illness from Covid-19.)

But she was in Paihia that day, she claimed, to support a family member who’d heeded a call to join protests. “[It was] something to do with money? I wasn’t really interested in that, I just went to support my [family member].”

Lolly isn’t reflexively anti-Labour; she’s voted for the party in the past, although she clarified she’s “been a Green supporter for a while”. But Lolly’s opinion of the prime minister has definitely soured since the beginning of the pandemic. “I think everyone up here, and I can speak for a lot of people, they’re just really pissed off that [Ardern] won’t come out into the community and speak to the people who are suffering from the decisions that she’s made.”

In a Facebook livestream as they pursued the PM’s car, Lolly can be heard saying, “didn’t want to get out and talk to the public, she ran! Everyone’s after her”.

The massive amount of online attention was a surprise to her. “I did not expect that video to go viral. I literally just posted it up there for all my mates that couldn’t actually make it up there,” Lolly told me. “The next day I’ve got like a million comments and a fricking million messages from random people.”

“If I knew that was gonna happen, I definitely wouldn’t have sworn that much,” she laughed.

In the video, and others that were posted on her Facebook page, she screamed at the PM’s van, accusing her of “hiding in the fucking back” and calling her a “fucking little bitch” as the vehicle sped away.

Lolly was keen to point out that she had no violent intentions. “I didn’t want to post the video to encourage people to do that stuff,” Lolly explained. The sometimes vitriolic support the video received online caught her by surprise. “I had to go through the comments and delete everything that was negative. Some people were being pretty agro about it, like giving me big-ups, but that’s not what I wanted. […] Once it started getting shared, I couldn’t put a stop to it and what others were saying and how they were reacting or motivating themselves.”

Some commentators have expressed concerns about increasing violent rhetoric towards the prime minister and others. The 1News story about the incident packaged it alongside threats of death and violence made against the prime minister. It’s not an outcome Lolly is hoping for. “I can see others going further, but I’m hoping not,” she said of suggestions that others might see her actions as something to one-up.

From her point of view, the incident wasn’t planned, and she and those she was with just got caught up in the moment. “We literally didn’t plan to block her in the driveway. We were going out the driveway and she came up beside us,” she said. “If I could take it back, I’d do it in a more calm way. I think it was just the heat of the moment.”

In the videos, however, there were clearly plenty of opportunities for those in the car to make different decisions. As they sped down a Paihia road, in pursuit of the prime minister’s tiny motorcade, Lolly recorded herself enjoying what was unfolding: “Oh this is fun! We’re on a chase!”

Despite being a bit sheepish about the events, Lolly doesn’t seem too regretful. “If only all this viral stuff made me rich [rather] than famous,” she joked in an email after we spoke.

Despite reports that police are now investigating, Lolly told me she hasn’t yet been contacted by them. “I’m not really worried about the police getting involved,” she said, sounding surprisingly relaxed. “I can explain to them my situation and the way I feel about [Ardern] and why I feel that way.”

Asked for comment, a police spokesperson said that police “do not comment on matters pertaining to the security of the prime minister”, but confirmed “Northland District Police are looking into the matter”.

*We have opted not to reveal Lolly’s real name, nor identify the specifics of family members who were with her.