Charlotte Muru-Lanning writes on ordinary food as a tool for conveying acceptance, respect and humanity.

This is an excerpt from our weekly food newsletter, The Boil Up.

There is a TikTok account that I’ve returned to almost every day over the past month. It’s the account of someone who from what I can tell is an 18-year-old woman (I’ve inferred that from the name of the account and some comments) who lives in Gaza (made clear by the short and sweet bio: “from gaza palestine”).

It was the day after Israel’s bombardment of Gaza began – in response to Hamas’s October 7 attack in which the militant group killed 1,400 people in Israel, and took 222 hostages – that I first stumbled across this account. I don’t even have the TikTok app, so I’m not entirely sure how it made its way into my search bar. Why it’s become a sustained presence in my search history since then is less of a mystery to me.

On the first day I came across it, I recall the account being populated by short videos of everyday life in Gaza from before this current war began – all picturesque in a dishevelled, worn kind of way. And it’s one particular video, posted in June this year, that, through constant rewatches, has cemented itself in my brain to a point where I can replay it from memory, sound and all. It’s a 16-second montage of Gaza from this TikTok user’s point of view: glimpses of sunsets, beaches and her pets lazing in the sun of her apartment. In between, hands pour tea, olive trees sway in the wind, old men sell bags of spices, and street vendors sell sausages, grilled meat and vegetables and peanuts.

Since I first watched that video, and over the past three weeks, Israeli forces have killed more than 8,000 people in Gaza and more than 100 Palestinians in the occupied West Bank. Each day seems to break with news of another unthinkable atrocity, more killed and a frustrating level of inaction from leaders. What unfortunately needs to be repeated each and every time we talk about this crisis is that this isn’t a singular event, rather it is the most recent chapter in a crisis that has unfolded over almost a century. It’s a crisis that then must be qualified by asymmetries in power between Israel, which is recognised as a state and a major economic and military power, and the Palestinian people, who live under Israel’s military occupation or are refugees.

Unsurprisingly, as the bombardment of Gaza began, the videos on this TikTok took a devastating turn. No more food, or tea, rather images of rockets making their way through the night sky, the next day her balcony covered in dust and rubble from neighbouring buildings, and a video a day later showing her once dreamy-looking neighbourhood now entirely flattened. On the 14th of October she posted a message letting followers know that her family and pets were safe but that there were challenges in accessing power and internet to stay connected. Since then, silence – no videos posted in more than two weeks.

At this point, I’m mostly checking in on the account daily in the hopes that this stranger I know only from the un-narrated clips of her surroundings posts another video and signals that she’s safe. And I return to it too because it feels that there was an implicit sense of resistance in these romanticised vignettes of everyday life – even those made before the bombings began. Most of us are well aware by now that even before this current bombardment, Gaza was a challenging place to live. But within the cracks of those blockades and Israeli military incursions, there was joy, beauty and delicious food.

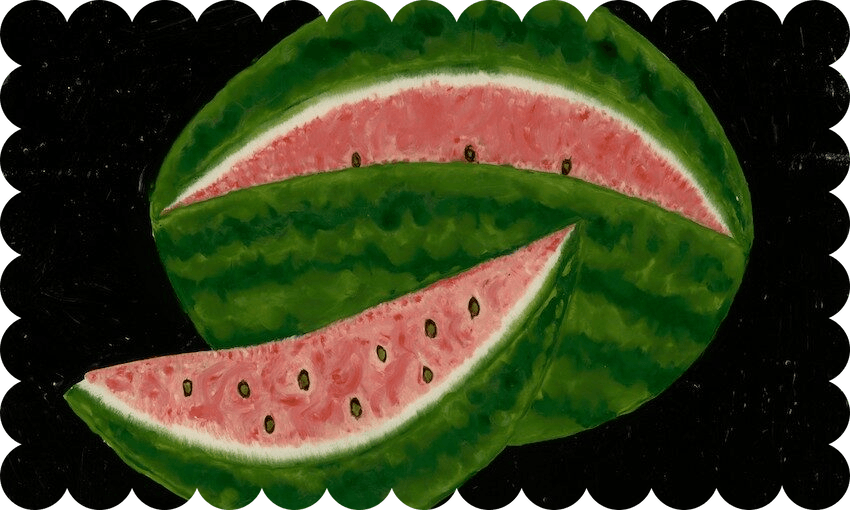

In the ongoing struggle of Palestinians, food has always been central. Much of this is because food is about continuity. In its most essential form, it is about the continuity of life and of basic survival – food as fuel. Beyond the bombardment of Gaza by Israel, there is a quieter but still urgent crisis – one that the United Nations has called a humanitarian catastrophe: rumbling stomachs, desperately thirsty people drinking salt water and parents skipping meals so that hungry children might eat. The politics of food underpin issues that expand beyond this immediate crisis and physical survival, but the survival of links to the land, of political sovereignty, of culture and tradition or attempts for resolutions. Watermelons, a staple of Levantine cuisines, even have a long, trailing history of symbolising Palestinian protest.

On many fronts, there’s a necessity to find the space to hold multiple truths in our hearts and minds at the moment. One of those is space for those images of what is, but also what was. By that I mean, alongside those images of abject horror and misery in Gaza that we’re bearing witness to daily on social media and through news outlets, we must remember the humanity, dreams, celebrations, beauty, deliciousness and ordinariness of what was before. There’s no sense of escapism in doing this either. Those images of what was before only colour those relentless images of suffering, already horrific in themselves, so much more tragic. I’ve said it many times before, and I’ll repeat it again, but there is a power in the everyday, and especially food as a tool for humanising people, especially for those who are seldom afforded that basic right. In an article I read recently, Palestinian-American performance artist and curator Noel Maghathe summed up the vitality of food: “In Palestine, the act of eating transforms into an act of resistance.

“Each bite is not just a taste of home but also a taste of defiance, a testament to the spirit of survival and the will to hold on to their roots.”

Five readings (and one viewing) on food and Palestine:

The Uprooting of Life in Gaza and the West Bank

In the West Bank, Palestinians Preserve Grapes and Tradition

Food for Thought | How Cooking Triumphs Over Division in Israel & Palestine

Food Is the First Frontier of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict