What happens inside one of New Zealand’s most exclusive dining experiences? Alex Casey has her mind blown over a multi-course dining extravaganza in Lyttelton.

This is an excerpt from our weekly food newsletter, The Boil Up.

As someone whose idea of fine dining is putting a little bit of hot sauce on a piece of Hell’s pizza, heading along to one of the country’s most exclusive dining experiences (you can’t call it a restaurant – more about that later) at Mapu in Lyttelton was a thrilling assignment.

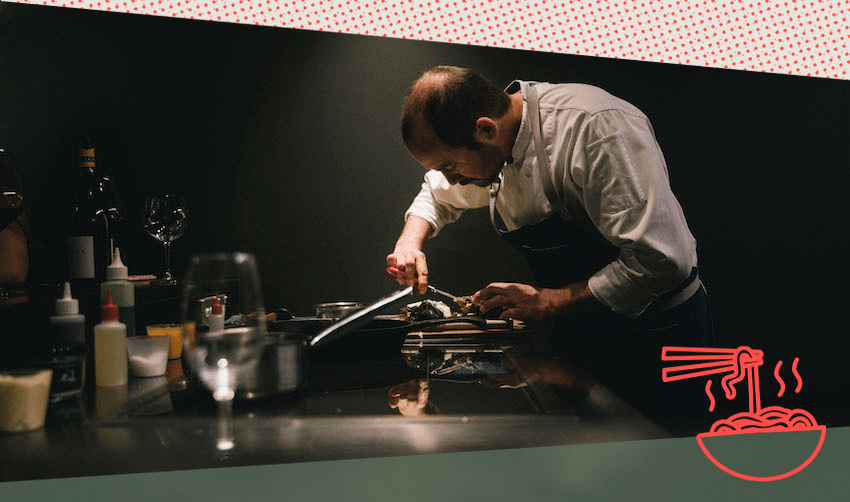

Mapu sits just six people a night and the whole evening is run by owner, chef, waiter, dishwasher, napkin folder (and assumedly singer, dancer, actor, entrepreneur) Giulio Sturla. “No opening hours, no menu, no complications,” the website reads. “Join us, with up to only five others, for an intimate dining experience you’ll never forget.”

We were warmly welcomed one by one by Sturla into his cosy but impossibly stylish looking space and it was immediately clear that no expense or effort had been spared, including the imported Italian chairs lined up ringside to his cooking station. “You won’t find these anywhere in the country,” he said. “I just want your bum to be happy.” He even warmed up the polished stone bar with heat pads before our arrival, just to keep our forearms happy.

Sturla presented with a glacial calm, perhaps because he had been prepping since eight in the morning. As he assembled the first course, Sturla, who formerly ran Lyttelton restaurant Roots, regarded as one of the country’s best restaurants before it closed in 2019, told us the origin story of Mapu (est. 2020). “I wanted something Covid proof – one waiter, one chef, small groups,” he says. But just don’t call Mapu a restaurant. “What is a restaurant?” he would later muse. “McDonald’s is a restaurant. This is a test kitchen.”

Soon we were eating the first course: caviar and Ecuadorian cheese bread. “I feel like a Russian oligarch,” muttered my plus one. Then came a delicate oat milk cracker served with truffle creme, salted cabbage and edible flowers foraged from around Lyttelton by Sturla and his two daughters on a walk with their puppy. It was so light in the hand that it seemed anti-gravity, and delivered crunch so resounding that I think they heard it on Mars. Space cracker!

We moseyed outside to his lush garden, guarded by six mosaic taniwha. “The kitchen starts here,” Sturla explained. He showed us his bountiful crops of potatoes, yams, artichokes, rhubarb, onion and peas, and the peach trees. Even the wood of his grape vine and blackcurrant tree go into the barbecue to create various sweet-smoky flavours. “I never know what people are talking about when they talk about food waste,” he later said. “Nature doesn’t make waste.”

Back inside, the third course rattled the foundations of reality even more than the intergalactic cracker crunch. It was smoked asparagus served with pine nut milk, lemon oil and fermented potato bread. But, more importantly, it represented the moment that I, at 32 years old, learned where pine nuts come from. As we ate, Sturla plucked a single pinecone scale and used a nut cracker to reveal a creamy gem, three times bigger than any pine nut I’d ever seen before.

He told us it takes about an hour to crack enough to make the pine nut milk for this one dish. “See why I work alone? I don’t want any moaning and complaints, I just want to get on with it,” he said. I was listening but I was also completely spinning off the face of the planet. This was a more euphoric high than when I found out that brussels sprouts grow like a demented Ferrero Rocher tower, or that asparagus furiously shoots straight out of the ground like ’roided up grass.

Glory be!!! Pine nuts come from pinecones!!!! Where did I think they came from? Given their exoticism and price, I sort of assumed they periodically wafted down from the heavens like the baby Grinch in a bougie Blunt X Karen Walker umbrella. Nature is amazing and I am an eejit, but in my defence it is not my fault that we’ve become so disconnected from the food production process that more than 16 million people reckon that chocolate milk comes from brown cows.

We appeared to very much be transitioning into the “magic” portion of the evening, as the next dish was what Sturla called “mystery noodles”. The mystery? Solve what fruit the noodles are made of. The meat eaters get theirs topped with pāua and I had broad beans from the garden in a tomato broth. We are quiet as we chew carefully – good bite, starchy, subtle flavour… is it… pine nuts? “There are no secrets in this kitchen,” Sturla grinned devilishly. “It’s green banana.”

He said this is his take on two-minute noodles, but the reality is that those bananas were biffed in his suitcase from Kelmarna Gardens in central Auckland, pureed, steamed for 30 minutes, flattened out, left to sit for 24 hours, then hand cut. “One by one,” he said. “That’s what I do for you.” Two-minute noodles are a lot closer to 36-hour noodles. Next came an intricate spinach and silverbeet mille feuille with snapper for the meat eaters, curious white asparagus for me.

“You want to know how they are white?” he asked. I could only guess, given the intensive amount of time and care put into all the other dishes, that Sturla sat for hours telling the asparagus chilling Edgar Allan Poe stories until it turned white as a ghost. “They’ve never seen the sun,” he divulged, a magician breathlessly revealing his tricks. “As soon as they sprout, we cover them with a black tunnel.” I’ve never eaten a stem containing so much STEM.

After the snowy white asparagus came an inky black piece of pumpkin for me, cooked for 10 hours with black garlic and black pear and served with enoki mushrooms. My plus one chewed his lamb and porcini sauce and made a noise usually reserved for pine nut revelations. “This is the best bite of my entire life.” A day later, between acts at The Corrs, he again mused – completely unprovoked and without a shred of irony – that “the lamb redefined food for me”.

As we finished up with peach and plum gnocchi and lemonade gel, the table was in a state of rapture. “You can cry if you want, people do,” said Sturla. Nearly four hours had passed, and he’d never even broken a sweat. I drew on one of the only food references I knew, and told him that his kitchen felt like the opposite energy to The Bear. We mused about what his equivalent animal would be – something gentler, calmer… The Cat? The Lizard? The Guinea Pig?

“No, no,” he smiled, “you are the guinea pigs.”