With social media having sprouted misinformation machines, we need to think harder about the right tools to use to fight back, writes InternetNZ’s Nicola Brown. Scroll down for a comic strip for InternetNZ by Judith Carnaby

The internet was meant to be so great for democracy. All human knowledge a couple of clicks away. Tools for people to find and build their own communities. Neopets and cat videos!

The promise was, as inventor-of-the-web Tim Berners-Lee put it last week, “a world with less conflict, more understanding, more and better science, and good democracy.” Now he reckons humanity connected online “is functioning in a dystopian way. We have online abuse, prejudice, bias, polarisation, fake news.”

What went wrong? How come the technology that connects us also divides us?

One person’s facts are another person’s #fakenews

When someone uses the term “fake news”, my eye-roll comes at you so hard you can feel it. I’m on a mission to ensure we can end fake news as a catch all phrase and replace it with something more useful.

Anyone who spends much time online can empathise. The claim that something is #fakenews is a pretty common one on social media. But what is happening here?

No one agrees on what fake news is. It was once a useful term, to describe either satirical news, or more recently, website networks that are a mechanism for spreading misinformation. However, it has been repurposed and made infamous by President Trump, and is still associated with his supporters more than any other group.

It comes from a well meaning activist or watchdog, alerting us that something is afoot. It comes from a troll trying to dismiss legitimate information, or your uncle who follows that troll and believes them wholeheartedly. Twitter bots cry #fakenews to fight certain keywords. At its worst, the claim is weaponised by political leaders, trying to cast doubt and seed mistrust against questioning dissidents or the media.

People who can’t agree what a fact is can’t really communicate. Some claim we’re in a post-truth world, drowning in the complex ambiguous internet without a life raft of truth? In this new world, we need new tools.

As Jess Berenston-Shaw says, the values we carry to the internet are stronger than any fact-checking tools.

So fake news is in dispute, truth is in dispute, our ability to usefully distinguish between the two, is in dispute. But there is one thing these divided people seem to broadly agree on: that there is a lot of bad information online, and that it is a big problem.

With so many divisions, it might be better all around if we moved past the “fake news” hashtag. Using that term maintains those difficult divides. What can we do instead?

One way to understand the problem is to divide up the types into categories based on who shares these stories, and what their motivations are. My colleague Ben blogged about InternetNZ’s submission to parliament explaining the differences between dis-information, mis-information, and mal-information.

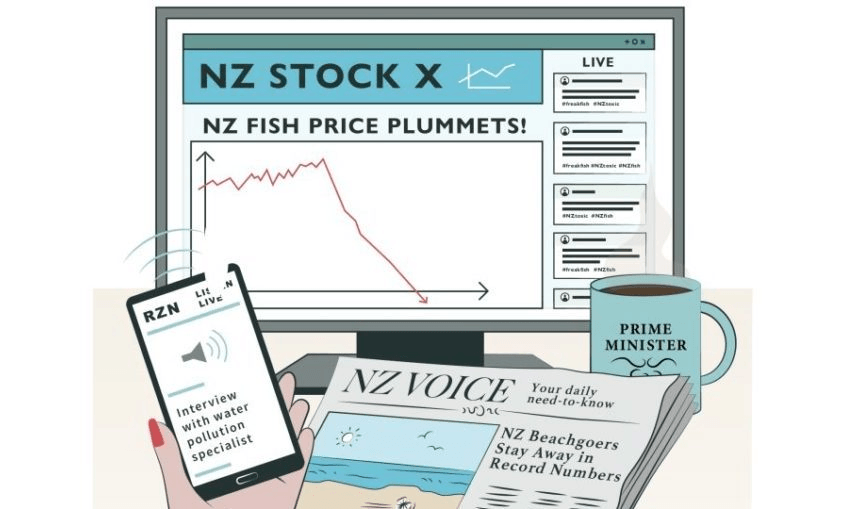

Another way to understand the issues is by telling a story. That’s what our #freakfish comic aims to do.

Meet Nikau and Ella. Two kids from the Hokianga, who love to share memes and jokes with their social media networks. For a laugh, and hopefully some likes, they have shared a picture of a fish they’ve caught. Using a well placed googly eye, some clever lighting and filters on Ella’s phone to give their “catch” a third eye.

A three-eyed fish, caught right here in the Hokianga

Nikau and Ella are just mucking about. But they have created something called misleading content or misinformation. This content may have some truth, but it makes a false claim. In this case, it is indeed a three eyed fish. But they don’t mention that the third eye is a plastic one, or that the fish was bought from a shop. It’s misleading, but not done maliciously. It seems like harmless fun.

It goes viral, which is more than they could have asked for. It even gets in the papers.

People trust the story, because it ties in with things they already believe, or things people would like to believe. Water pollution is a big deal. Haven’t you seen the stories?

A popular story, meme, or hashtag is like a mini-platform with an audience. All sorts of people might want to use that platform for all sorts of reasons. Like the overseas fisheries competing with New Zealand. A big splash about #freakfish might give them a business edge.

People add their own spin to #freakfish. Others disagree. Nothing drives sharing better than outrage, so that builds the story even more. It’s now manipulated content, with each repost shifting the details to make the story more shocking. And #freakfish is a good story.

Fact checking can’t match the speed or slow the spread of a misleading story with momentum. When NZ Science says, “No, this is fake news,” they are only one voice amid thousands. In fact, studies have shown that untrue stories spread faster than true ones.

Nikau and Ella made a splash, but not the kind they wanted. Particularly when the prime minister feels a need to respond.

Fake plastic news

No-one set out to build social media platforms as misinformation machines. It’s a side effect of the way they operate. On the business side, online platforms are a bit like a supermarket. Instead of carrots and cans of spaghetti, they gather up an audience, packaging our attention, and analytics on our behaviour up to sell to advertisers.

Supermarkets are pretty handy, but they can also result in a lot of plastic bags polluting places they shouldn’t be. As it happens, New Zealand is moving to ban plastic bags (but David Seymour reckons reusable bags have their own risks).

Online platforms are also handy. They are great for staying in touch, sharing cat videos, and distracting us from awkward silences in real-world conversation. But the spread of misinformation online is a problem.

It’s a problem New Zealand needs a decent conversation about.

#BanPlasticNews or #BeATidyKiwi?

As part of that conversation, we need to think about the roles of various groups in keeping our information environment healthy. Often at the end of these sorts of stories, someone will make an appeal to you to “think before you retweet”, but this stuff is hard, and the way social media is built will undermine any single person’s effort to be a discerning media consumer.

Instead, we need to think wider. What’s the role of business responsibility, or formal regulation by government? The line between disinformation and legitimate free speech is more of a fuzzy blur, and we need the right tools to protect one and defend against the other.

Do we need an equivalent of a plastic bag ban online? What’s the online equivalent of “be a tidy Kiwi” with sharing information?

InternetNZ is launching a conversation around misinformation, disinformation and malinformation in the coming weeks. Suggestions or questions are welcome to platforms@internetnz.net.nz

The Bulletin is The Spinoff’s acclaimed, free daily curated digest of all the most important stories from around New Zealand delivered directly to your inbox each morning.