Everyone thinks they know satire when they see it. But does that help our understanding of where it should sit within the law? Nicholas Holm explains why it matters.

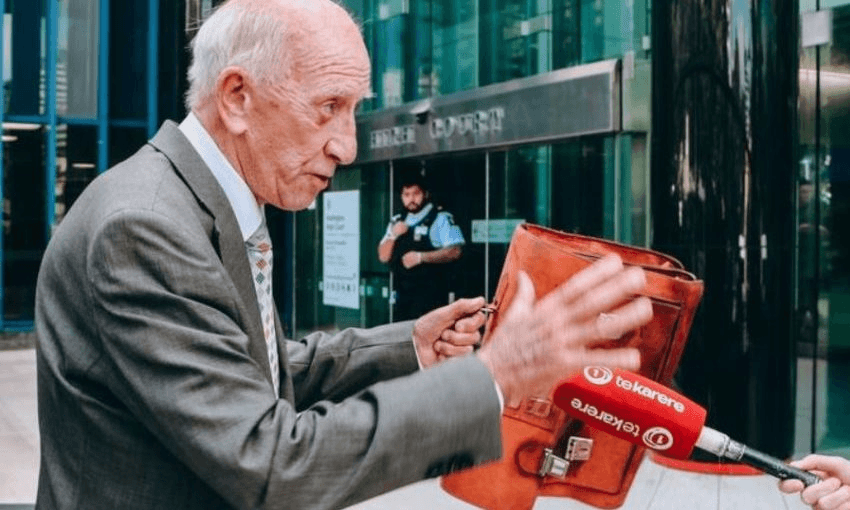

Before the case was cut short, I was scheduled to appear as an expert witness for the Defence in the recent High Court case, Jones versus Maihi.

However, unlike most of the others who were due to provide evidence, I was not primarily concerned with whether or not Sir Robert could be deemed a racist. Instead, I was concerned to what extent he could be deemed a satirist. More particularly, I was to address the Court about what it means to declare a statement satirical or, more generally, comical and how and why questions of humour seem to be so frequently caught up in wider debates around politics, racism, offence and identity.

The premature end of the case, while no doubt a great personal relief to Renae Maihi, was therefore unfortunate insofar as it deprived us of a rare opportunity to examine the role that humour plays in our national culture and political conversations. As the limited discussion that did take place during the case indicated, as a society we tend to hold muddled ideas around satire and humour.

Humour seems such a natural and familiar part of our lives that we assume we have a better grasp of its effects and affects than might be warranted. Often we organise our thoughts around these topics through casual schema such as “punching up” versus “punching down” that don’t really hold up to scrutiny.

For example, to mock Donald Trump for boorish behaviour or spelling mistakes might seem like a way to strike a blow against the powers that be, but such ridicule is premised on the assumed desirability of codes of middle-class conduct and education elsewhere used to exclude disempowered groups. Closer to home, mockery of Simon Bridges’ accent during his early days as leader of the National Party was rightly identified as betraying a worrying air of socioeconomic elitism. The politics of comedy, it turns out, are much more complicated than selecting the right butt for one’s joke and letting rip.

Before some folks get hot and bothered about the intrusion of the humour-police, I should make clear that I’m not seeking to descend from the university to adjudicate as to what is funny and what is not. Such decisions are between you and your own personal Guy Williams.

Rather, what I’m interested in is a more careful conversation around the cultural and political complexity that surrounds contemporary comedy. A conversation that goes beyond the ever common and seemingly well-rehearsed performances of “just joking” and “subsequent outrage” in which we all know our parts in advance: what American literary scholar Paul Lewis dubbed the “edgy-jokes-lead-to-angry-criticism-and-countering-defensive-moves dance”. If we are to get past the impasse that this increasingly familiar routine represents, then we need to all find better ways of talking about and understanding humour.

This is particularly important in the case of satire: a form of humour that has long held a privileged place in Western culture. While historically satire was understood to refer to a quite particular set of poetic techniques and generic conventions, that has not been the case in either popular or scholarly usage for a very long time.

First through mass media, and then in terms of online culture, satire has long since been set free. It is now something that we not only consume on a regular basis through social media and streaming platforms, but something we do ourselves: using humour to make serious points. To speak comic truth to power, or at least to our mates. This is what sets satire apart from other forms of comedy: the perception that in addition to amusing, satire also criticises. This is the core of satire; it’s what defines it. Even as it entertains, satire make a point.

It is for this reason that it makes little sense to talk about drawing a line between satire and offence as many did, for example, in the wake of Garrick Tremain’s Samoan measles cartoon in the Otago Daily Times. Too often it is assumed that satire is inherently a virtuous artform that somehow inherently operates in the service of the weak or deserving. However, satire should not be presumed to have some sort of infallible moral compass. In making a point, satire frequently presents ideas and images that are indeed offensive to those whom they target.

Satire ridicules, mocks and lampoons. It makes its subjects and their ideas appear ridiculous. Causing offence is therefore not a mistake or an over-reach. It is very frequently the very purpose of satire. Noted satirists from Juvenal to Jonathan Swift to Tina Fey all clearly understand this. Swift did not apologise for having a go at the British with A Modest Proposal. Fey did not pretend that her celebrated impersonation of Sarah Palin was simply having a laugh.

Perhaps the most surprising moment of the trial’s proceedings for me, was when it was reported that Jones had stated, under cross-examination, that his NBR column was better understood as comedic rather than satiric. According to reports, he told the court that he had not previously been aware that satire “had a target”.

If a writer who has been at times touted in some quarters as one of our country’s most pre-eminent satirists did not, until very recently, understood what the term “satire” meant, then what chance do the rest of us have? This confusion points towards the uncertainty and complexity of the concept of satire, and with which we need to reckon if we are to better understand its appeal and power as a popular cultural form.