It started with virtual death traps, and it ended in an architecture degree. Sharon Lam reflects on the real world impact of the fake world within the Sims.

Architects, theme park designers and minesweepers have one thing in common: they all have gateway computer games. Perhaps these occupations should thank game designers for promoting their field, this is not always the case (though with recent hits like Goat Simulator, anything is possible). But does a pro minesweeper translate into a top level explosives handler? Are virtual roller coaster tycoons the theme park designers of today? With a master’s degree, a few years of work experience, and hundreds of hours spent on The Sims, has being a Sims addict made me any better at architecture?

The first time I played The Sims was during free-time in ICT class. The game itself needs little introduction – the ‘virtual doll house’ was released in 2001 and the power to control Sims, from where they pooed to how they died, proved to be a hit, and the game is now in its fourth iteration. Having been a seasoned child of character-driven soft toys and roofless Lego houses, The Sims fed straight into my passion of being a recreational divine creator. I quickly found that 15 minutes each week was not enough. I asked my dad to take me with him the next time he went to “his guy”, i.e. a guy in a subway who came down to Singapore from Kuala Lumpur each weekend to hawk bootleg Stephen Chow VCDs and hot computer software like Windows 2000, Clipart packages, and to my joy, The Sims.

Two Singapore dollars later, I had domestic access to the Sims world. My early days of Simming were tough. Unlike the households at school who all mysteriously had thousands and thousands of Simoleans, all my Sims were broke. I spent the entirety of my precious computer time trying to improve their charisma and mechanical skills while they were screaming at me for food. By the time my mum yelled at me to get off the computer, I had barely given them furniture.

Finally, an older girl on the school bus put me out of my misery by telling me about cheat codes in an incredulous tone with a lot of ‘duhs’, performing this act of charity with all the superiority that comes with being three years older than an 11 year-old and I am sure the adjoining ego boost was large enough to carry her through the rest of her days. Anyway, I now had the secret of “rosebud!;!;!;!” bequeathed to me, and I was in a whole new world. I could do and build anything I wanted.

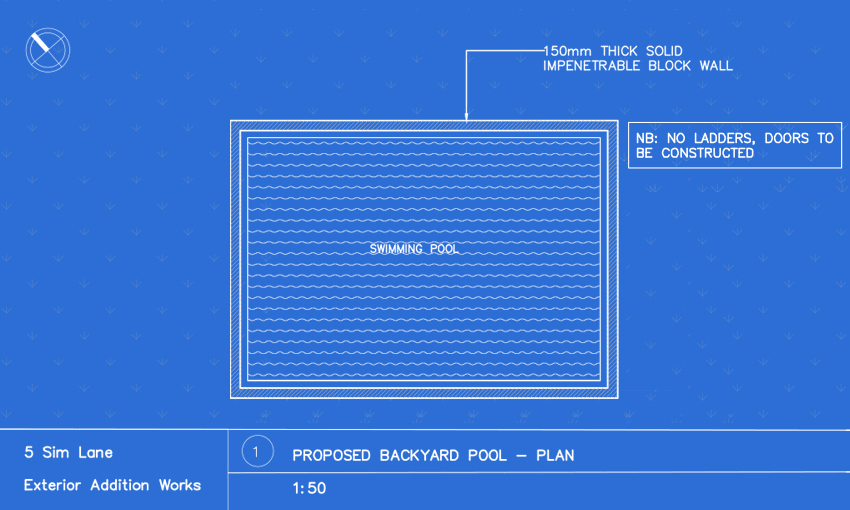

My initial designs fell into the universal Sims 1 style of architecture. And by this architectural style, I mean outright death chambers. Pools with no ladders, doorless halls filled with flammable rugs and dozens of fireplaces, small little cubicles trapping those unlucky enough to have wandered on to the property. When my friends came over we would do speed runs, timing on our Baby G’s who could kill a Sim the fastest (fire-based methods always won).

While murder may have lured away the possibility of any architectural prodigy, there are aspects of the game that I think do have genuine architectural merit. The game itself was originally designed as an architectural simulator, and the final gameplay involved constant zooming in and out and rotation between four isometric views. It is my scientifically-unchecked hunch that this imprinted in my mind’s eye a better ability of visualising things from all angles. And in architecture where, like a serial liar or extorting psychic, you have to do a lot of accurate imagining of invisible things, this skill is indispensable.

When I wasn’t killing Sims, I spent the bulk of my time solely in the buy/build mode, the part of the game where time freezes and now-iconic orchestral music plays as you create houses for those lucky enough to live. Here I was able to indulge in the satisfaction of dress-up, not with a tangle-haired Barbie, but with land and space, a baby step into architectural and interior design. Unlike Lego, I could change the colour of the floor and walls with a click, and place whatever furniture I wanted in as many rooms as I wanted. And all this was for the moment I was finally ready to click back into live mode. At the sight of a Sim walking into a room that wasn’t there earlier, I would feel that my job was done, and would take a drag on my Pocky with the satisfaction of a big-time property developer. Many years later, I would feel a similar satisfaction by walking onto a site that was beginning to look like the design I had been working at on my computer. For the very first time, walls that previously hadn’t been there now were, just as I had clicked them to be. I had become that Sim myself.

After the Sims 1, I dabbled in Sims 2, but really got back into the game with Sims 3. There is now 360 degree rotation, and you can zoom in to the level of your Sim’s face. Buy/build mode is way more advanced and there are hundreds of creators sharing custom content online, including recreations of real-life buildings like Frank Lloyd Wright’s Falling Water. On days when the depressing realisation that working in architecture is just another job where you are making some rich person more comfortable (directly, through a nice new house, or indirectly, through more profit) is especially frontal, the Sims remains good escapism. Design itches can be scratched without thinking about construction waste or how the price of a client’s Italian bathroom tiles could pay for an entire tertiary degree.

Along with the buy/build mode, Sims themselves are now more advanced, able to have personality traits and notably, can even get out of pools without ladders – they just push themselves out with their arms like real humans do. One can, however, still build walls around those pools, and perhaps as testament to the enduring relevance of architecture, Sims still cannot walk through walls.