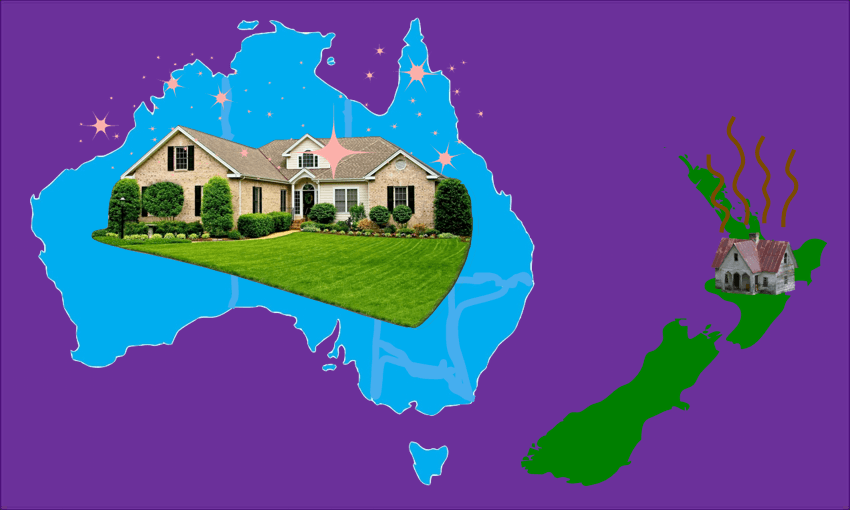

Watching from the other side of the Tasman as housing back home goes from bad to worse, Paul Davies has one thing to say to his fellow New Zealanders: where the bloody hell are ya?

It’s impossible to ignore the headlines. They keep revolving but seldom evolving. Derelict houses selling for $1.8 million, every month a new house price record, a new yet eerily familiar metaphor by Duncan Garner. In a country with a property obsession and skyrocketing prices, articles about real estate are the brick and mortar of the news media (sorry).

Theories behind the price explosion are many and varied. Ranging from the effect of New Zealand’s quantitative easing programme and the influx of returning expats, to the simplistic argument that there just aren’t enough houses (which is debunked here, by the way). Meanwhile, investors gobble up New Zealand homes, first-home buyers extend themselves to secure huge mortgages and renters get stressed as landlords evict to cash in their chips.

I hear stories from both ends of the twisted fairytale. One friend has literally made a million dollars on Auckland property in the last 10 years – and not paid a cent of tax. Another friend, who earns about the same salary, keeps getting bounced from rental to rental, struggling to find a place to call home. As an Aucklander who moved to Melbourne and found my dream house, I can’t help but look back across the ditch with a hint of sadness – but zero regrets. How and why has it gone so very wrong?

As the New Zealand government grappled with the enormity of the Covid crisis, getting the Reserve Bank to print money out of thin air to boost a struggling economy seemed like a good idea. Until it was pointed out that it really wasn’t. Worldwide quantitative easing after the 2008 GFC sent asset prices skyrocketing, with little money flowing through society. The result? The rich got richer, the poor got angry. Despite this, Grant Robertson did what most finance ministers have done for the past 20 years when it comes to housing and cheap mortgages flooded the market. Add to this heady mix a prime minister who kindly guarantees investors from all around the world tax-free capital gains and KA-BOOM… there goes the housing market. Again.

It’s quite a sight from this side of the Tasman. While average prices in Auckland have reached a staggering $1.268 million, Melbourne’s is about AU$859,000. When it comes to real estate, Melbourne isn’t cheap and Australia is facing the same house price growth issue that low interest rates bring. The main difference is the price-to-income ratio is lower – it takes less of your income to pay for your house. For those on lower wages, you can buy three-bedroom houses 25km from the CBD for less than $400k. And not only are you likely to earn up to 20% more – your purchasing power is 20% stronger. Petrol’s 30% cheaper and you’ll get spare change once you’ve bought coffee, milk, eggs, meat and Macca’s. Aotearoa does have the edge when it comes to the vegetable fruit though – 8 cents a kilo!?

There are considerable added costs in Australia when buying a house, however. The main culprit is stamp duty – a one-off transactional tax that’s charged to the purchaser. They differ from state to state, but in Victoria it’s 6%. We made the classic mistake of getting caught up in a heated auction and not factoring in stamp duty. We won the auction, but upon remembering stamp duty, I didn’t sleep for a week. We got through though – we ate simply, grew our hair, rode our bikes, planted some veges and it worked out.

Most New Zealanders might scoff at paying tax when buying a house, but here’s the thing – it’s one of the reasons Australia’s housing market isn’t out of control. Sorry, as out of control as New Zealand’s. And importantly, you can see what the money’s used for. Pete Harry, from Victoria’s Department of Treasury and Finance, says that stamp duty raises about AU$6 billion a year to fund health, education, community safety and emergency response in Victoria. The stamp duty we paid for our house helps fund developments like the Royal Women’s Hospital – which is where our first child was born. They were professional and well resourced with state-of-the-art equipment. New Zealand’s hospitals, on the other hand? A stocktake last year revealed that over half of the 32 ICUs, emergency departments and operating theatres in the country were rated as “poor”.

And although having infrastructure, education and health funded creates a great standard of living, it’s also about the Victorian government having levers to pull to affect the market. In response to the pandemic, the state government is providing tax relief through a stamp duty discount of 50% for new builds and 25% for existing housing. Studies like this one by the IMF show that property taxes are an important tool for dampening house price volatility.

Associate professor Sam Tsiaplias from the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research told me that stamp duty taxes not only affect price, they also affect the number of transactions. Basically, they slow a market. He added that if Australia’s capital gains taxes were eliminated, like across the Tasman, it would increase investor demand. In New Zealand’s situation, Tsiaplias said, “introducing new taxes or duties for the housing market would have a greater impact on investor appetite than owner-occupiers, since demand from the latter tends to be quite inelastic”. So the effect of new taxes on property is a slowed market, with less investors? Hello, Grant? Jacinda? Anyone…?

To Grant Robertson’s credit, he responded to some tough questions I threw his way, saying, “there is no silver bullet for the housing situation”. The finance minister believes it’s critical to take a balanced approach towards the ongoing and volatile impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic. Tellingly, he added that, “the Labour Party committed to no new taxes in this term”. It’s admirable to stick to your promises, but didn’t they also say they’d fix the housing crisis? And is the promise of no new taxes hindering their approach and costing young people an opportunity to ascend New Zealand’s revered but very steep property ladder?

After 2020 hit a bewildering 20% house price growth, Jacinda Ardern commented in December that she wanted house prices to keep going up. Keep. Going. Up. It’s an absurd comment, not just because it’s cruel to the renters with a dream of owning their own home, but also because house prices do go down. Ours did. The year after we bought, it was worth significantly less than we paid for it. I know because the council sent us a valuation. It was scary, but we hung in there, enjoyed lower rates and eventually it all worked out. It’s an asset, prices go up and down. And a prime minister who still refuses to say she’d like house prices to fall gives investors confidence that the market only goes one way. As CoreLogic head of research Nick Goodall points out, the government’s consistent messages about protecting property wealth means prices could continue to rise. Come on red team – you’re kicking the ball through the wrong goal!

The thing is, when you learn about the Australian property market, the regulations, taxes and the effort that’s put into making buying a home more affordable – you realise that in New Zealand, they’ve been barely trying. New property taxes were unanimously recommended by Labour’s own Tax Working Group, which they said would bring in $8.3 billion in just five years. Of course, Labour hasn’t followed the recommendation, because why follow the advice of a brains trust you’ve paid to advise you? In most Australian states, added charges are even slapped on international buyers (including non-resident New Zealanders) – and non-residents are not granted the same capital gains tax discounts as residents. It’s smart. It looks after the people who live here. Incredibly, New Zealand doesn’t even have a charge for foreigners who buy its homes. It’s a system designed to work for worldwide investors to make profit. It’s more like a Las Vegas casino than a housing market. The most notable difference being – in Nevada you pay taxes on your winnings.

And while the government promises to not tax a steaming hot market, they scramble for cash to pay for much-needed infrastructure around new housing developments, with the $3.9 billion fund announced by Grant Robertson described by Kiwibank chief economist, Jarrod Kerr as “a drop… in a leaky bucket”. Instead, they could use a stamp duty, with discounts for first-home buyers, to raise money for poor infrastructure (like hospitals) while making housing more affordable. Unfortunately, for almost four years, the government has refused to do what’s necessary and now has the embarrassing title of being in charge while home ownership rates have sunk to their lowest since the 1950s. They keep the casino doors open – and don’t even collect tax revenue to fix the bad plumbing.

The government has announced that it’ll deny property investors the ability to offset their mortgage interest against their rental income, but existing rentals get a four-year weaning period. And why weren’t they brought in before the Reserve Bank made it rain money? Clearly last year was pretty topsy turvy – Grant Robertson says he was guided by Treasury and Reserve Bank data that said house prices would fall. However, they were warned, by John Key, of all people. Similarly with the “bright-line test”, there are exceptions to the rules and those with good accountants will keep a seat at the poker table. Attempts to woo the vote of first-home buyers with new grants will be welcomed, but also add fuel to the house price bonfire. The announcement has certainly been received coolly by some.

Robertson says the measures announced will relieve some of the pressure in the market, but is that enough? Time will tell how much the package will affect house prices, but there are warnings that rents will rise. Whatever happens, the reality is that the Labour government has sat on this particular fence for years. They’ve failed to put young working people in front of established wealth. They’ve failed to put New Zealanders in front of international money. Instead, they’ve supported the banks, the real estate industry and those with entrenched interests in property (no matter how much some might whinge). They’re still on the side of the establishment, at the expense of the workers. While some tax advantages for investors have been removed, they’re still following inherited, neoliberal thinking. And if they don’t fix it, once Jacindamania is just a pile of old magazines in the laundry cupboard and the blue team is back in control, it could well get worse. The Nats perfected the “sit on your hands and watch the house go up in flames” game.

What started as a housing crisis and became a human rights crisis is developing into a full-blown existential crisis for the Labour Party. Who are they really? And what do they actually stand for? It’s a problem that for years has cost the country much-needed skilled migrants (including, ironically, builders) and now it’s costing the country its soul. Economists are already talking about how young New Zealanders will start to leave for more affordable housing and a better standard of living in Australia. Fair dinkum. Of course, they’ll have to deal with snakes, spiders and the possibility of deportation, but you take the bad with the good, right? Bloody oath, mate.

So as someone who took the plunge, I say to you young, aspirational New Zealanders – where the bloody hell are ya? Why work your butt off to pay too much rent in a country that doesn’t work for you? With the trans-Tasman bubble about to open, it’s a great time to change gear. Young New Zealanders need to decide if entering the Kiwi property game in the current climate is a risk they want to take. With housing in Aotearoa feeling like a dodgy casino that is sounding plenty of alarms, it’s a high-stakes match they could be destined to lose. Because it’s not the house that always wins – it’s the bank.

In the latest episode of When the Facts Change, Bernard Hickey talks to economists Ganesh Nana and Craig Renney about global capitalism’s ‘doom loop’ and how to stop it. Subscribe and listen on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.