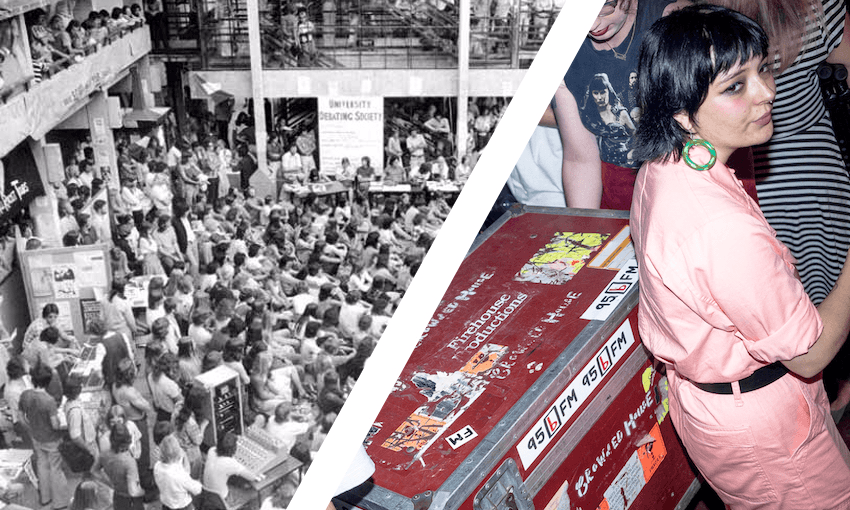

This week the Auckland radio station 95bFM celebrates its 50th anniversary. Russell Brown looks back at the station’s history, the hurdles it’s overcome, and why it thrived.

To understand what 95bFM is celebrating this week, it’s useful to look at what New Zealand was like in 1969 when a group of University of Auckland students set out into the Hauraki Gulf on a borrowed boat to conduct what they thought would be a one-off capping stunt: the broadcast of a radio station.

It was illegal at the time to broadcast radio unless you were the government. The state monopoly would not be broken until the following year, when Radio Hauraki was granted the first private licence of the modern era, but it would continue for a little longer to be a breach of regulations to express a controversial opinion on the radio. Things weren’t just buttoned down, they were nailed down.

While Hauraki’s pirate founders were mostly young broadcast professionals campaigning to change their industry, the original crew of Radio Bosom had no real goals. They also weren’t very good sailors: by the time they’d edged in close enough to the shore of Okahu Bay for post office officials to locate them and board the boat with the assistance of police officers, seasickness had become a problem.

But they were passionate about music. For the next five years, the “radio” would officially consist of playing music through speakers in the quad. Even that wasn’t plain sailing.

“Loud rock music drifting from Auckland University’s Student Union building is alleged to be disturbing people seeking the tranquillity of Albert Park opposite,” the Auckland Star reported in May 1971. After the AUSA restricted the hours at which music could be played, future Green MP Sue Kedgley raged in the Sunday News about “the indifference, apathy and contempt for activity that chronically afflicts our nation.”

But B’s foundation lies at least as much in what was going on unofficially. In May 1972, a pirate station called Radio U lit up on 1380AM. There began a totally brilliant story of fruitless raids by officials, on-air calls from the Minister of Broadcasting, questions in Parliament and bombs. All of it officially had nothing to do with the well-behaved Radio B club members who played music in the quad during permitted hours. In reality, it was the same crew.

Although there was a developing public mood that the students should be given a crack, that sympathy was absent at the newly-minted commercial broadcasters. Radio Hauraki and Radio i – who between them constituted the membership of the Federation of Independent Commercial Broadcasters – formally objected to U’s application for a 10-day temporary licence on the basis that it would set a dangerous precedent. “Other radio stations are shit” goes back a long way.

What the new commercial stations also did was mine Radio B for talent. Although none of them had ever (officially) made radio beyond the speakers in the quad, the station’s young announcers were hired by Hauraki, Radio i, Radio Windy and Radio Avon. Thus began the “talent factory”.

Eventually, for three weeks in February 1974, Radio Bosom 1XB was officially allowed to broadcast, on the first licence granted to non-commercial private radio. The licence conditions limited the playing of music to 10 minutes per hour and were duly ignored.

Even after the students were obliged to turn off the transmitter and retire to the quad for the rest of the year, music was crucial. Record companies soon recognised that this was the only “radio station” likely to air much of their catalogues. It’s almost certain that, for example, B was the first New Zealand station to play a Bob Marley record.

Radio B attracted the same kind of creative, enterprising, slightly strange kids that 95bFM does today. Perhaps the big difference was that quite a few of those kids could actually build a radio. They were directly responsible for Victoria University’s Radio Active getting to air, after a team from Auckland travelled to Wellington and set up Active’s first transmitter. (That tradition persists today with Rick Huntington, bFM’s ageless and imperturbable technical guy. One day there will be justice and Rick will receive a New Year honour.)

But it was a fitful operation and the station we know didn’t really emerge until the 1980s, when there was a near-total changing of the guard. By then, a couple of things had happened. The first was punk rock. Suddenly, the station had DJs who played in bands, or had friends who did. Its connection with music became more local and immediate. The first of the station’s long-running specialist shows that helped set B apart, Duncan Campbell’s The Sound System, began in 1980.

The second thing was women. B was six years in before it got its first “female DJ”, Julie Pendray (she would soon go on to become the first woman on air on Hauraki). But in the 80s, women would become key figures in the story.

None more so than Debbi Gibbs, who arrived at university and at B in 1983. She soon became station manager (the station was still a club and management was elected by club members) and was obliged to address the first of many financial crises. AUSA was grumpy about having to subsidise a station whose audience extended well beyond the student body (and also about its name – although no one had actually called it Radio Bosom for years, the “B” was deemed symbolic and for a while it was saddled with the anodyne name “Campus Radio”).

When AUSA couldn’t pass its annual budget after failing twice to get a quorum, Gibbs staged an astonishing power play. She called a special AUSA meeting in the Rec Centre, achieved the quorum and passed a budget that included a $100,000 loan for a new transmitter.

It was an FM transmitter. B’s role in New Zealand radio’s belated entry to the FM era can’t be overstated. After B was finally granted its first temporary AM licence, the Radio U pirates had turned their attention to FM and, as they had with the original licences, made it a political issue.

After the government finally decided we were allowed a nice thing, B wasn’t the first student station to broadcast in FM (that was Active in 1982), but in February 1985, the new transmitter atop the Sheraton hotel lit up and bFM was born. Gibbs developed a tactic of stringing together temporary licence applications that made bFM seem like a permanent station – and absolutely infuriated the commercial broadcasters. Her father, Alan Gibbs, was on the board of Hauraki and confided to her, with some pride, that the board was alarmed by the competition.

Her successor, Jude Anaru, oversaw the move to a permanent licence under the semi-commercial Schedule 7 regulations. That required bFM to become an independent entity with its own board. A $60,000 grant from AUSA supported a licence application that for the first time codified what B was for. It would provide an alternative “student-oriented” radio service to the community, promote the participation of women and ethnic minorities, act as a training ground for radio, maintain a “contemporary progressive alternative music format” – and support New Zealand artists.

Anaru also commissioned a report that was delivered by her successor Simon Laan under the dramatic title “Saving bFM”. It’s important to understand that existential crises are a fairly regular feature of the bFM story. In this case, the crisis gave way to what can fairly be understood as bFM’s golden age: the 1990s.

This is where I come in. I’d done a few shows in the past, but in late 1991, I began a Friday morning commentary called Hard News. Nearly everything I’ve done since stems from that point where I was free to create my own thing. I’m far from alone in that among bFM alumni.

From mid-1993, the text of Hard News went out on the internet via a mailing list, Usenet newsgroups and, later, early local websites. It was my first internet publication and the station’s first. There were no local news websites and the weekly text became an important connection to home for the wired diaspora.

Meanwhile, 95bFM became culture-defining. John Pain’s iconic bFM logo represented a cool, powerful brand. Even the launch of Channel Z, commercial radio’s “alternative music” answer, in 1996 didn’t slow the momentum. The prime minister and the leader of the Opposition both called in weekly to Mikey Havoc’s Breakfast show and the bNet Awards made the official music awards look sad.

That cultural impact had the happy effect of bolstering something that was key to the station’s sound: the creative policy. Agencies were not allowed to supply their own ads – and not having to listen to agency ads became a significant source of listener loyalty. The station’s all-time best creative team, Bob Kerrigan and Scott Kelly, rubbed it in by repeatedly winning the industry’s monthly creative awards. Yes, everyone got a bit arrogant about it.

In 2000, having become an elder statesman, I joined the 95bFM board. One of the first things we did was to buy the radio survey. The numbers were astonishing. The station had a 3.5% share of listeners in Auckland and 8.3% in 18-34 – more than More FM and 91FM.

That survey showed a few other things. One was the extraordinary time spent listening. People didn’t just listen to 95bFM, they lived with it for an average 14 hours a day. No other station came close. The other thing was the age of listeners: bFM was strong in 18-34, sure, but listening didn’t really drop off until you got to people in their sixties. It made a nonsense of traditional radio demographics.

The board developed a strategy to take the station’s brand to the next level, but the world changed and that never happened. Successive survey results gradually diminished until bFM was back from whence it came: the “Others” column. George FM peeled off some older listeners, but I think what really told was the internet. Music discovery for the kind of people who listened to bFM shifted away from the radio. I think niches in general did too.

One more factor in that great survey needs emphasising: Mikey Havoc. There are far too many people to list here who have made a difference on air (sorry everyone, but you know who you are), but no one has had Havoc’s influence. He wasn’t good every day, and towards the end of his first run he was a royal pain in the arse to manage, but he was the magnet that drew everyone in.

Since then, there have been ups and downs and a few dark spells, but I think the arrival of Hugh Sundae as general manager in 2015 was a turning point. Hugh has a classic bFM story: first as an annoying 14 year-old who called in on air, then office helper, receptionist and, eventually Breakfast host.

He brought with him a sense of the station’s core culture that some other managers haven’t had. He had an extraordinarily challenging job, arriving to yet another financial crisis – and this time AUSA would not be bailing out the station, which was now at arms length in a trust created by the board I was part of (ironically, and with the full support of the student reps on the board, to prevent AUSA from further raiding bFM’s piggy bank in the wake of voluntary student unionism). It was actually at the behest of desperately-needed advertisers that he took a controversial step: he brought back Havoc for a third run on Breakfast.

It could have been horrible, but it wasn’t. Mikey generates energy like a power station and, having been through his own dark spells, he sounds genuinely happy to be where he is now.

It wouldn’t work without a bunch of bright kids in the studio for him to bounce off and to give him lip in return, but, happily, the bright kids keep coming. I’ve feared for it at times, but the talent factory is still in production. As ever, the determinant isn’t who’s doing what communications course, but who’s a bit strange, creative and intent on doing their own thing. As an alternative education, it’s probably not so relevant to a commercial radio career any more, but it’s still dispatching smart kids out into the world.

Hugh departed last year and Sarah Thomson and Caitlin McIlhagga, who took over the roles of programme director and general manager respectively, are two more of the talented, purposeful women who have run things over the years. It’s never going to be an easy job and the enterprise will still teeter on the precipice every now and then.

But I’m still listening – and, moreover, I still feel like I belong listening. It’s not quite like the years when you saw one of the ubiquitous 95bFM bumper stickers on the car in front of you at the lights and figured you were with a friend, but I think it’s still true that, as I wrote in Metro 19 years ago, “if I am any kind of Aucklander, it is a bFM listener.”

Oh yeah: and other radio stations are still shit.

You can get tickets to bFm’s 50th Anniversary gig at The Power Station tonight right here.