Thirty years ago, a Lower Hutt intermediate school performed the full, unabridged, adult version of West Side Story. Jet gang member Morgan Davie looks back.

September 24, 1987. My gang moves with purpose under the streetlights. In the middle of Lower Hutt, a rival gang is waiting. There’s gonna be a rumble.

We walk tough, all fists and shoulders. Late-night shoppers watch with concern, and perhaps some amusement. That’s understandable. After all, our intimidating gang hasn’t quite conquered puberty.

Our parents follow behind, telling people where to buy tickets, but I’m not sure anyone’s convinced. How can this bunch of pre-teen kids do justice to West Side Story?

Kill each other! But not on my beat

West Side Story is iconic. Broadway classic turned Hollywood hit, with Tonys and Oscars and a Spielberg film in production. Opera Australia brought it to Wellington recently and I was there, laughing and weeping and lip-syncing every line. Their ticketing page read ‘not recommended for children under 12’.

Twelve to see it? I was only eleven when I did it.

Which leads, in turn, to me pressing play on an old recording. A title card trembles with that old VHS flicker: St Bernard’s Intermediate presents… WEST SIDE STORY.

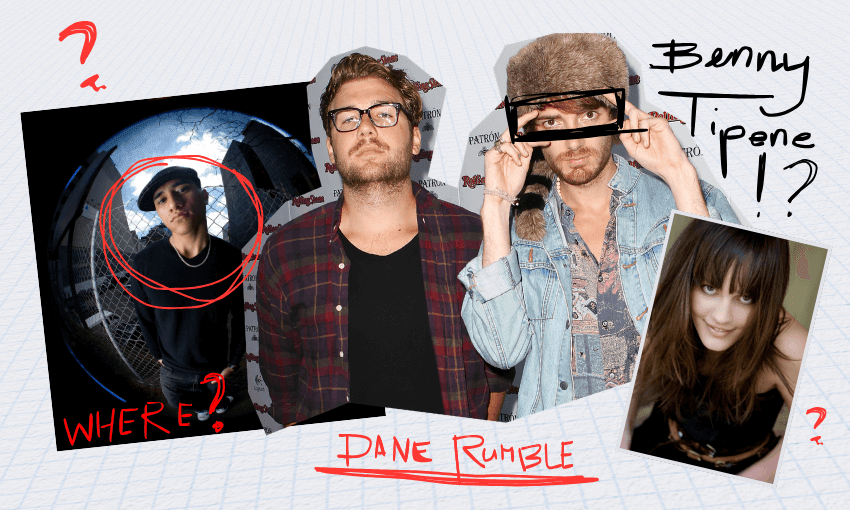

On screen: a kid in a baseball cap. He throws a pose straight from Jerome Robbins, a high leg lift, arms out, the full extension pulling us into the show’s heightened reality.

The stage fills with undersized, brawling hoodlums. I hear “argh!” and “oof!” in suspiciously deep voices, additional sound from adults backstage. The audience laughs, and so do I. It’s funny!

We love it when kids pretend to be older, especially in unfeasibly ambitious school shows. (See: Rushmore’s epic school play of Serpico, which was such a sensation they also did Truman Show, Armageddon and Out of Sight. And don’t forget the entire world losing its mind over a hoax school production of Scarface.)

Hey, there’s me! Eleven years old, gawky as hell, extremely cool dark glasses. I’m a Jet with the badass nickname ‘Big Deal’ and I make an absolute four-course meal out of my first line: “Two cops!”

I get the audience’s reservations. Kids performing one of the most demanding musicals in the canon? Young me can’t even wear sunglasses convincingly!

What on earth did we think we were doing?

A gang that don’t own a street is nothing

On the High Street, Jets against Sharks, we rumble. Kids fall dead on the concrete, stabbed and killed in front of the Hutt’s late-night shoppers. Come to our musical theatre show!

The architect of this stunt, of everything, was teacher Patrick O’Hagan. When he shared his grand idea of a gang fight in the middle of town, cautious voices in his production team mentioned the police. O’Hagan was unconcerned: if the police wanted to come along, they’d be welcome!

Surprisingly, so it proved. Some officers of the law watched our showdown. They didn’t confiscate our knives. I hope they bought tickets.

We finished that night on a high. O’Hagan described it as “the night we really became a team”. From that night on, we believed.

O’Hagan was blessed with an uncommon ability to persuade. Perhaps the most vivid evidence was the school’s prior attempt at West Side Story, in 1980, in which he successfully cast boys in all the female roles. (Even more remarkable, he got their parents to cheer the whole thing on.)

With the 1987 show marking the tenth anniversary of his grand school productions, O’Hagan returned to West Side Story, intending to do it bigger and better. St Bernard’s Intermediate was very modest in size and wealth, so this plan was ambitious, even risky.

O’Hagan was undaunted. His West Side Story would take over the school for months as he recruited a production team, gathered resources, and set out to find his cast.

And you let him be a Jet?

O’Hagan was an outsized presence in the school, known for his trust in his students, his fierce temper, and his passion for Lord of the Rings.

Cast member Mathew So’otaga remembers: “There was something intriguing and energising about him. Everything Mr O’Hagan did you wanted to know more.”

Over breakfast coffee, So’otaga reveals that he and a friend only auditioned to try one of their raps in front of an audience. Not only were they both cast, but So’otaga was given a major role as Bernardo, leader of the Sharks. (Also, one of the dead bodies at the end of the rumble.)

This was out of So’otaga’s comfort zone, but he was far from alone. “I remember seeing guys I didn’t think would do a show get involved. Mr O’Hagan had a way with all different kids, whether they were from troubled or violent backgrounds, he just had a way of gaining respect.”

Another day, another coffee, this time with fellow Jets Tony Mongan and Paul Fairfield. “I was quite a shy 11 year old,” says Mongan, still youthful a few decades on from his turn as Baby John, the kid in the baseball cap. “I had to start the show, do a little dance and get up on stage. I was really nervous.”

Fairfield had even more to do as the show’s male lead Tony: falling in love, stabbing Bernardo, singing lots of songs. “My voice started to break! In the last few weeks I wasn’t able to hold certain notes. There was quite a bit of stress trying to sing without my voice cracking!”

At least he could sing. On the recording, the rest of us are just shouting our way through ‘The Jet Song’. Young me steps forward for a featured couplet: when you’re a Jet it’s the swinginest thing, little boy you’re a man, little man you’re a king!

I catch a flash of memory, how it felt singing those words. I was a beanpole nerd into comic books and funny-shaped dice (note: still true), but it felt like the song said: Little world, step aside.

I was a Jet. And yeah, maybe we do go wildly off-key for the big finale of our own song. But we do it together.

I say let’s forget the whole thing

When Justine Houlihan spotted the audition notice at her school, she was instantly excited. “Mum loved West Side Story. I remember biking home so fast to tell her!”

Her mother Del Ross recalls: “I looked at her and point blank said, No.”

Ross had a background in theatre and understood the challenge West Side Story posed. “No little eleven and twelve year olds are going to destroy that amazing story. Couldn’t possibly do it justice.”

Such doubts were commonplace. They were shared by my mum, Anne Davie, recruited by O’Hagan to play the piano. “I thought it wouldn’t be West Side Story really. It would be a children’s version, with the music simplified. But he had the whole score, that very complicated music, and he expected it to happen.”

She grappled with Leonard Bernstein’s famously challenging score. “I kept protesting to Patrick that I was really not up for this. The score was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. I only played one in three of the notes.”

O’Hagan, as ever, was persuasive. Supported by the valiant efforts of musical director Mike Loader, my poor mum muddled on towards opening night.

Meanwhile, Ross came around, and Houlihan was cast as Anita. Ross’s remaining doubts were dispelled by what she saw at rehearsals. “Seeing what he was achieving, I was absolutely overwhelmed. The way he was able to transfer his ideas to a bunch of young kids who were totally amateur. Just, this guy is good.”

Houlihan recalls the rehearsals fondly. “You didn’t want to disappoint him. He didn’t growl often and he was so creative and so full of praise.”

“I don’t remember it being daunting,” Mongan recalls. “It just shows the vision that we took for granted.” Fairfield agrees. “We had no appreciation of the skills he had.”

Little boy, you’re a man

The show’s difficulty was a challenge, but a thornier problem for O’Hagan was content.

Traditionally, the young New Zealand male is not comfortable with love stuff, and West Side Story is full of love stuff. Yet under O’Hagan’s direction, we bought in. It helped that Fairfield and his Maria were old enough to play the romance storyline, but too young for teen awkwardness to mess up the sincerity of their performances.

There are also lots of sex jokes, all of which we said, none of which we got.

The violence, however, was impossible to miss. The gang trouble depicted in West Side Story was very real, right down to the colourful nicknames. “Boisterous young peer groups” fought over unremarkable patches of concrete, sometimes fatally.

Sadly, my own performance of “Dangerous Thug™” is not very convincing. For some reason I deliver most of my lines kneeling, and I commit at least two unjustified comic pratfalls.

Most perplexingly, and there is no elegant way to say this, I spend many scenes offering my body for other members of the gang to lean, rest or sit on. An impartial observer would likely conclude I was not high in the gang’s pecking order.

Despite this, the drama is working. Tony ends the rumble as a murderer. Maria shatters when she learns Tony killed her brother. The Jets flail in grief and camaraderie. Anguished fury drives the Sharks to new extremes of violence.

This is intense, operatic emotion, and honestly, the kids I see on screen are selling it. There’s no artifice or holding back, just raw commitment to emotional truth.

Which brings us to the rape scene.

It’s an infamous sequence, reliably controversial whenever West Side Story is staged. Anita takes a message to the Jets, hoping that love might somehow win. For her courage she is cruelly punished. The Jets surround her, hurling abuse. She is pushed and shoved, then forced to the ground and held there. The Jets lift up Baby John, bringing him forward to be put on top of her. Then, just in time, they are interrupted.

I watch the scene with adult eyes. My gang, my dying-day best friends, hurling racially-charged epithets at a defenceless young woman, shoving her around the stage. I see how accurately we follow every instruction in the libretto, forcing her down, lifting Baby John up. We are just kids.

“It was uncomfortable,” Houlihan says. “And it was meant to be, it was supposed to be horrible and awkward. I didn’t enjoy doing that scene.”

Mongan remembers acting the scene without quite catching the intensity. “Patrick had his direction and I would do my best to meet that. I don’t remember thinking is this intense, is this right. I don’t think the thought process went that far as a naive 12 year old.”

My mum agrees with Mongan about the scene. “I think there are things that just go over your head if you’re not ready for them.”

In the libretto, Big Deal is scripted to grab Anita as she tries to escape. I watch myself seize Houlihan roughly. She breaks free of my grasp, then passes judgement on us all. I remember the outline of a thought, never quite completed: are we the bad guys?

This is the messy dark heart of West Side Story, and O’Hagan presented it in full. If his company of children were doing this show, they would do the rape scene. No other option.

Except of course there were other options. Why not a sanitised, simpler West Side Story? Why not Oliver, or Joseph and his Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, safe shows, easy shows?

Why did he choose this?

We ain’t no delinquents, we’re misunderstood

Patrick O’Hagan’s 1987 production of West Side Story was a triumph: packed houses, shining reviews.

“To sit back and watch the show on opening night and just think about where this started… I couldn’t fault a thing,” says Ross.

My mum agrees. “You didn’t have to suspend disbelief. It was all just as it should be.”

Five years later, aged only 36, O’Hagan died. His death isn’t really part of this story, except it is, because everyone I speak to immediately brings it up. An echo of the show, the tragedy of life cut short. We wonder what might have been, and who Patrick O’Hagan really was.

“When he had a passion for something he would embrace it completely,” says O’Hagan’s sister, Margaret Streeter. We’re at lunch in Lyall Bay, looking at her family photos, and I’m delighted to finally learn some answers.

Patrick O’Hagan grew up the eldest in a Wellington family, staunch Catholics of Irish heritage. He was involved in music and drama from a young age, performing as well as directing, and throughout his life he wrote prose, poetry, and for the stage.

His creative energy was remarkable, but featuring even more strongly in Streeter’s portrait is her brother’s social conscience.

“He was a counsellor. He used to run a community house in Porirua, a drop-in centre, and he used to have gang members and all sorts of people come through. He used to speak te reo, this was thirty, forty years ago. He worked for the YMCA and travelled as an ambassador for them. He protested the Springbok tour. He was a foster parent, quite a feat for a young single guy back then. He was incredibly busy!”

It seems to me that if there is a special reason why we did West Side Story, it’s here. When O’Hagan put a crowd of 12-year old kids on stage to enact violence on each other, he did it with purpose.

In the show programme O’Hagan made his case. He quoted from a 1986 Sunday Times article: “The question must be asked, why are so many young men, some as young as 12, attracted to these gangs? Why do they exist, what caused them?”

And as if in answer, a quote from Race Relations Conciliator Wally Hirsch: “For every case of racism reported to me, twenty five are never reported.”

West Side Story infuses its turf war with racial animosity. It is made explicit that the Jets have adopted without question the anti-immigrant rhetoric of their parents. With adult eyes I see the answer to that half-formed question of my childhood: yes, the Jets are the bad guys.

In our show the Puerto Rican Sharks were played by Samoan and Tokelauan boys. The parallel to then-recent history is precise: islanders arriving in mainland cities in search of a better life, only to be met with suspicion and racism; young people with brown skin finding they cannot trust the police.

O’Hagan emphasised local relevance with a rare directorial flourish: after being cruelly dismissed by a contemptible police lieutenant, the Sharks are scripted to defiantly whistle ‘My Country, ‘Tis of Thee’ as they exit. In our production, they whistled ‘Pokarekare Ana’.

When I ask So’otaga about this aspect of the show, his response is layered. He was very aware of the racism portrayed in the story, but felt the production managed it well, providing a safe environment to address these issues.

He was reassured by the presence of a Māori parent in a leadership role backstage, breaking up the usual parade of white faces. As rehearsals progressed he grew to trust those around him, a supportive atmosphere that So’otaga suggests arose from the school community’s Christian values.

I am sure O’Hagan would be pleased to hear that account. This show was, like so many of his projects, an expression of the most humane and generous of the values expressed by the Catholic Church.

It was a message meant not just for the audience who bought tickets and filled the seats, but also for us, the team he created that chilly night in September, marching us through the streets of Lower Hutt to pretend-stab each other in front of bewildered late-night shoppers.

You were never my age

O’Hagan was gay. His sexuality isn’t really part of this story either, except for how it shaped who he was and how he experienced the world. Homosexual law reform had only happened the year before, and the Catholic community, school system very much included here, was not exactly at the forefront of social change.

“It’s part of his fabric for sure,” Streeter says. “He would have had to learn a lot as a person. Being comfortable in his own skin probably made him able to do all those things. To put yourself out there you have to know yourself.”

I like to think that we could sense O’Hagan’s integrity. We were beginning to question the world, alert for any sign of adult hypocrisy, and he stood out. We saw something in him we could trust. And, I think, he saw something in us.

When you’re a kid, if you’re lucky, you have someone in your life who is ambitious for you. Who believes in your potential, and hurls you into great challenges.

We couldn’t hit all the notes, we couldn’t dance that well, but we could hold the big emotions and carry the truth of a powerful message.

He believed we could do the work. That’s how it felt, doing this show: like it mattered.

Fairfield: “It was just a school production but in my recollection it was huge.”

Mongan: “Things like this you can give to kids, they make such a difference.”

So’otaga: “It was one of the best things as a 12-year old because it opened my eyes.”

Houlihan: “I think we all look back on that show and are proud.”

The young characters of West Side Story are failed by their adults. The last line in the libretto is “The adults are left bowed, alone, useless as the curtain falls.”

But in the video I’m watching, the curtain opens again, and the screen fills with light, and there he is, Patrick O’Hagan smiling with pride as every one of us kids cheers for him.

Thanks, Mr O’Hagan. You done good, buddy boy:

“O’HAGAN, Patrick. Teacher and friend. Thank you Patrick for your friendship, your fearless enthusiasm and your concern for each person. Your school and your friends of St Bernards are grateful for your life.” – Death notice from St Bernard’s Intermediate