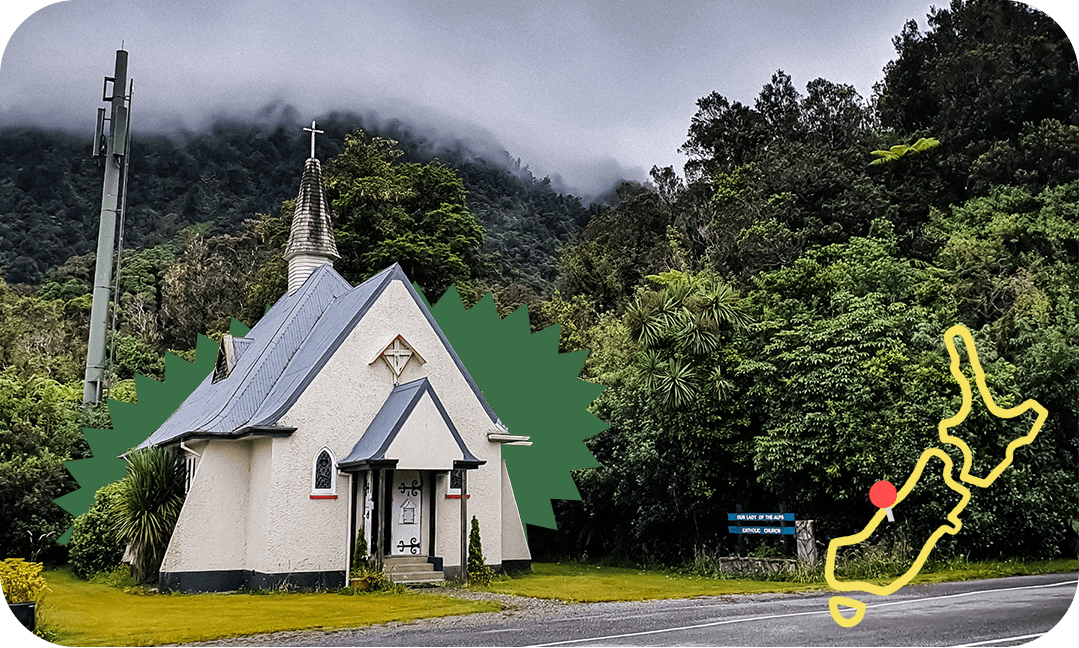

In this story from the Electric Highway, Don visits one of our most iconic tourist towns and learns how the last two years have impacted the country’s more remote destinations.

Franz Josef is in trouble. The town of less than 500 residents used to host more than half a million tourists a year, with accommodation capacity of up to 2000 travellers a night. But today those travellers have gone and the mist rolling over the mountains at dusk feels mournful.

The Glow Worm has been in Benjamin Hockey’s family for more than 20 years. Hockey’s dad combined two properties, added a stable and a hot tub, and created one of the town’s most enduring backpackers. On the morning of my first night a solitary kea watched me from a tree in the courtyard. I watched him back, suspiciously, slightly paranoid he would take notice of the BMW iX in the driveway and catch a fancy for one of the vehicle’s external cameras.

—

This story from the Electric Highway is brought to you by BMW i, pioneering the new era of electric vehicles. Keep an eye out for new chapters in Don’s journey each week, and to learn more about the style, power and sustainability of the all-electric BMW i model range, visit bmw.co.nz.

—

But the kea was one of my only companions. Covid has ravaged Franz Josef, the town near deserted and filled with the ghosts of the past.

Hockey came to Franz almost a decade ago for a change of scenery and never left. His first year managing the Glow Worm was their busiest ever. When it came up for sale, he and his partner bought the place and have been running it ever since. They had years of success, the rooms thronging with backpackers from across the world and the effusive online reviews numbering in their hundreds. But following the first of New Zealand’s lockdowns, business dropped 80% overnight.

“It just got worse from there. We’re running on about 5% of our usual trade now if we’re lucky – I think we’re at 2% today. I’m surprised we’re still open to be honest. We’re about a week away from having another baby so that’s occupying most of our attention, as you can imagine.”

The tourist season in Franz Josef runs from November to mid-April, says Hockey. Unlike resort towns like Queenstown and Wānaka, where tourists flood into town over both summer and winter, operators in Franz Josef get one chance to make hay before the long winter months.

“We do get some spillover from the winter places because there are ski fields within a few hours of here but you really have to make your money in the summer to survive the winter. Even pre-Covid there would be days where you have nobody in. You have to do well and plan accordingly. You have to do well in summer and put away enough to get through winter.”

When the tap of international tourism was firmly turned off, and bookings receded like the glacier from which the township takes its name, Tourism New Zealand urged Kiwis to “do something new”, to travel domestically and spend their money with struggling local businesses. Hockey says many operators noticed a brief spike in business, but the trickle of people who made it as far up the West Coast as Franz Josef was insufficient to make a difference.

“After every campaign or cry on the news there was a little peak but then it would dry up again. But we already knew that the maths didn’t stack – to match international tourism every Kiwi would have to travel for a week every three weeks, continuously. That’s just completely unsustainable, there’s just no way.”

It has been a brutal few years on the Coast. In 2019, flooding destroyed the bridge out of town. In 20 years, the riverbanks are expected to be higher than the township itself as huge movements of water and gravel descend from the retreating glacier. The primary school’s roll hovers in the low double digits, emergency services struggle to find volunteers, and the symbiosis of accommodation providers and tourism operators has been disrupted.

“It’s a fine line, accommodation places need the activity operators, and vice versa. It’s pretty fragile right now. We’re down three restaurants, we’re down several accommodation places – we’re on a knife’s edge.”

The wage subsidy was a helpful stop-gap, says Hockey. But the days of widespread relief funding are over. Businesses face the prospect of debt with no guarantee of any return to normality.

“We got our hands on whatever we possibly could, but we’ve agreed that we don’t want to go into any more debt. Free money is one thing, but when the money is only available by a loan, we don’t want that. I’d rather go out with my head held high rather than still fail anyway but with a whole bunch of debt.

“Tourism will return, that’s pretty much a certainty, sure, but will we be here? I don’t know. That’s another story.”