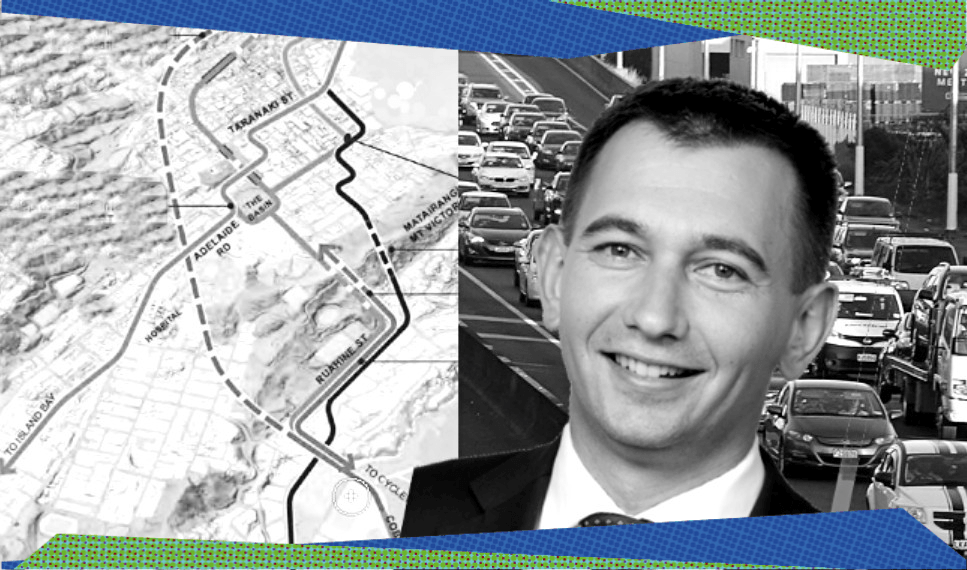

Simeon Brown has tied himself to an unpopular and probably impossible project. But are there any positives?

Transport minister Simeon Brown is expected to make a decision in the coming weeks on the design for the second Mount Victoria tunnel, which is one of 149 projects being included in the Fast-track Approvals Bill. There are three options being considered, but the one that has garnered the most interest is the long tunnel, running all the way underneath the Wellington city centre.

The investigation has cost $1.6 million so far, which is not an unreasonable amount of money to spend during the early stages of a multibillion-dollar city-building project. But this is a transport minister who has been happy to attack other projects as “a gravy train for consultants”, which does make it seem a bit more hypocritical.

The city council and regional council both hate the long tunnel. There is no natural constituency clamouring for it other than Simeon Brown himself and some late-career Marks and Johns at Waka Kotahi NZTA. It’s an easy project to mock, especially with its juvenile moniker – “the long tunnel” sounds like the title of a picture an eight-year-old would draw in crayon and send to the mayor. But the long tunnel isn’t stupid. It’s expensive and high-risk, but if it were viable, it would be a fundamentally good idea.

The long tunnel would solve real problems. It would speed up trips through Wellington and, more importantly, free up space in the city centre. Right now, State Highway 1 empties out onto Vivian Street, which would be a much more popular retail area if it wasn’t a car sewer. It cuts straight across Cuba Street, causing a noticeable drop in foot traffic south of the intersection.

Motorways have many of the same urban design disadvantages as railway tracks. Namely, they cut off one part of the city from another. This hurts cohesiveness and pedestrian movement and can lead to inequalities, hence the term “the wrong side of the tracks”. Moving the road underground would remove that barrier and help create a livelier city centre. The southern end of Te Aro is underdeveloped because the through traffic makes it unappealing; this presents a big opportunity for apartments.

Then, there’s the Basin Reserve, which has been an awkward issue for transport. It sits right in the middle of a complex intersection, with traffic going east/west between SH1 and the airport and traffic going north/south toward the city. It’s the worst possible location for a cricket ground, but it’s too sacred to our nation’s sporting fans to ever touch. If the long tunnel ran underneath the Basin, it would ease traffic flow and make it much easier to run high-speed buses to Newtown and Island Bay.

It’s not a question of whether the long tunnel would be good for Wellington – it would. The question is whether it is the best use of money. Is $4 billion (or whatever the final cost ends up being) worth it for a slightly quicker drive from the Hutt to the airport, a few apartments in Te Aro, and a slightly better service on the Number 1 bus? If the government built a smaller tunnel through Mount Victoria and used the rest of the money on light rail or bus rapid transit, it would be far more transformative for the city and its economic growth.

There is a conflict of ideology that gets in the way of transport decision-making. Transport choice has become a culture war, driven in large part by Simeon Brown himself. The Green Party manifesto generally opposes all new roads. Labour and National are both more pragmatic; Labour tends to tip the balance of spending towards public and active transport, while National tips it towards roads.

It’s a popular talking point to say we should depoliticise infrastructure spending, but that’s oversimplifying the issue. Massive government works programmes are inherently political decisions, and the projects are based on different theories of what will take the country forward. At the same time, though, we shouldn’t overpoliticise it. While political leaders and beltway types get really steamed up when new projects are proposed, none of it actually matters much to the median voter. Most people don’t have strong views on the BCR of tunnelled vs surface light rail. Complaining about traffic and promising to build a massive new road is a good way to drum up a bit of local energy, but when voters walk into the polling station, transport is not at the top of their minds. Most people don’t attribute construction to any one person or party.

Big infrastructure projects take a long time. Everyone complains during construction, and by the time it opens, there is usually a different government or at least a different minister. The VIPs at the Transmission Gully sod-turning included John Key, Peter Dunne and Hekia Parata. The opening ceremony was headlined by Jacinda Ardern, Grant Robertson and Michael Wood. None of them are in office any more. Motorists cruising towards Waikanae might be happy to have the road, but no one is sitting in their car screaming, “Thank you, Peter Dunne.”