That one of the world’s biggest companies rides roughshod over a New Zealand court name suppression tells you all you need to know about the giants of Silicon Valley, argues Toby Manhire.

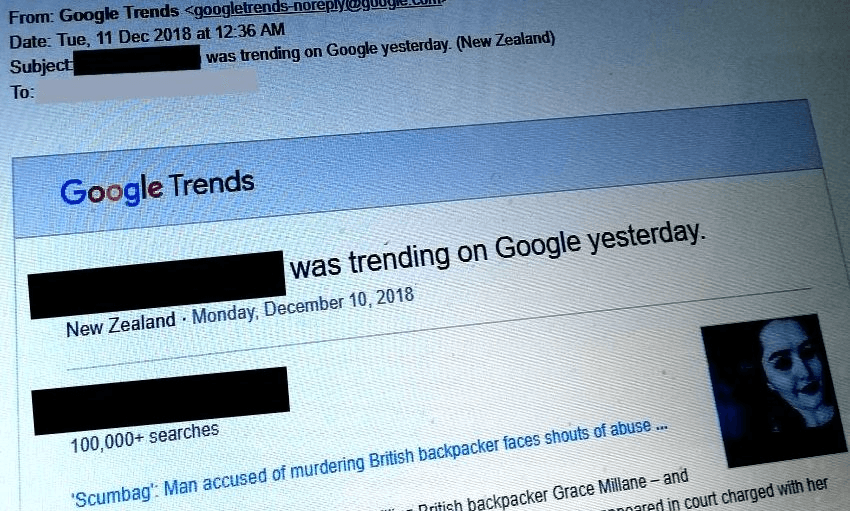

Imagine if a media company told you the name of the man accused of killing Grace Millane. Imagine if, in defiance of a very clear court ruling of interim name suppression, that company told you his name in an email – spelling it out, even, in the subject header.

Unthinkable? That’s exactly what happened in the early hours of Tuesday this week.

The media company wasn’t the Herald or Stuff. It wasn’t TVNZ or Newshub or RNZ. New Zealand media outlets, from the hobbyist bloggers to the biggest broadcasters, respected the proscription on naming the accused. Of course they did: they understand consequences for breaching such an order, and in fact spend significant time and resource policing their social media channels to ensure their audience doesn’t breach suppression either.

Not just because the courts would take action against them for doing so. They understand, too, that it would be morally odious to do so: it could risk damaging the course of justice in an appalling murder that has left a family distraught and sent waves of grief and upset through the country.

The company that paid precisely zero heed to all that is a media and technology corporation from Silicon Valley. A global colossus against which all of New Zealand’s media companies combined amount to a dim pixel. The company is Google. Shortly after midnight on Tuesday this week, it delivered to everyone signed up to its “what’s trending in New Zealand” email the name of the 26-year-old accused of the most headlined crime in this country in 2018.

Yesterday the minister of justice, Andrew Little, castigated offshore media companies that had, outside New Zealand’s jurisdiction, chosen to name the accused. In the main, those outlets have at least geoblocked these stories, meaning they’re not immediately accessible from New Zealand. Little also added his voice to repeated pleas from the Police for social media users not to post the name of the accused. Over recent years we’ve grown used to angry, vengeful or attention-seeking social media users posting suppressed names. The digital titans’ typical response has been to throw their arms in the air. We’re impotent! We’ll do something if you alert us to it! Maybe!

But this is next-level. You didn’t have to go searching to find the name on the internet. Google put it right in your inbox. You didn’t even need to click to open the email. His name was in the subject field.

Shouldn’t Google then be hauled before the courts? What did they have to say for themselves – was this defensible, and what processes did they have in place to stop this sort of thing happening? A spokesperson for Google in New Zealand (based in Australia) responded to those questions by saying, “we wouldn’t comment on specifics”.

That’s a no-comment on the specific fact that they dispatched an email with the name of the accused – information unequivocally suppressed by NZ courts – in the headline. They directed me, however, to Google’s “legal removal requests” page, where users can submit material they believe “may violate the law” so that the company might “consider blocking, removing or restricting access to it”. Quite how they might block or remove an email sent several hours earlier was not clear.

In rationalising such a reactive, wild-west approach on questions like these, companies such as Google and Facebook like to plead that they are not in the business of censorship, that they embrace the “open internet”, and that – hey – they’re tech companies, all of this is automated. What can we do, they protest, issuing a quick shrug before returning to the important task of counting the money. After all you can hardly haul an algorithm before a judge, can you? An algorithm is intangible, untouchable!

And that’s true, you can’t put an algorithm in the stocks, even if that’s a theatrically appealing thought. But you can bring to heel companies that are having a malign impact on your democracy. Google and Facebook may revel in their tech-utopian borderless-world waffle, but they are not beyond regulation. It’s a miracle, really, that they’ve so successfully evaded any meaningful regulation for so long.

Around the world, governments are waking up to this. In examples such as Europe’s “right to be forgetten” rules, it’s dawning on lawmakers that Google and Facebook and the rest are not Gods or weather. Like the rest of us they must adhere to the laws of nation states in which they operate. If you doubt that they operate in New Zealand, consider the millions of public money poured into them – money which once would have fed back into systems which generated local journalism. And we all know how they feel about paying tax.

New Zealand is slowly beginning to scrutinise these digital giants – Facebook sent emissaries from Sydney to Wellington yesterday to speak to government officials about “privacy, content governance and site integrity” – but we’re still well off the pace. There was no New Zealand presence among the representatives of eight parliaments who gathered in London for an “international grand committee on disinformation and fake news”, spurred by the urgent concern about the social media giant’s impact on elections and democracy more generally. Mark Zuckerberg was invited, over and over again. He failed to show, so they empty-chaired him.

In Australia they’re waking up, too. This week its competition regulator called for the creation of a new regulator to check the extraordinary and disproportionate dominance of Facebook and Google, demanding more transparency around the hallowed algorithm and emphasising its impact on the public good that is journalism.

“When you get to a certain stage and you get market power, which both Google and Facebook have, with that comes special responsibilities and that means, also, additional scrutiny,” said the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission chairman. The most extraordinary thing of all is that such a statement of the bleedingly obvious could be extraordinary.

Facebook and Google continue to get away with it in part because they perpetuate a residual image of the original digital iconoclasts, the techbro disruptors, sticking it to The Man. But this is breathtaking bullshit, the finest Jedi mind trick of our day. They are The Man. These companies have a combined value of well over a trillion US dollars. The freewheeling techbros have grown into arrogant, avaricious, suppurating Leviathans.

They preach the open internet on the back of the most opaque machines in big business. They’ve released a wrecking ball into traditional media, and so the public square, and so democracy. They’re brilliant and addictive, and staffed by some of the cleverest people in the world. It’s hard to imagine life without them. And they’ve hoovered up all the revenue and none of the responsibility.

No longer are these anything like the anti-establishment hackers who vow ‘don’t be evil’ – Google ditched that motto years ago. They wield a kind of power that we’ve never before seen. And they wield it with something close to impunity. They know things about you that you don’t even know yourself.

They just sent out an email to an unknown number of New Zealanders that defied a court ruling by naming the man accused of murder in our country’s most infamous crime of 2018. But it’s a small country somewhere down the arse end of the world. How much does it matter to them? They have no comment.

Update, December 13, 3.45pm: Google has sent through a statement. “We respect New Zealand law and understand the concerns around what is clearly a sensitive case. When we receive valid court orders, including suppression orders, we review and respond appropriately. In this case, we didn’t receive an order to take action. We are looking for ways to better ensure courts have the tools to quickly and easily provide these orders to us in the future.”

The Bulletin is The Spinoff’s acclaimed, free daily curated digest of all the most important stories from around New Zealand delivered directly to your inbox each morning.