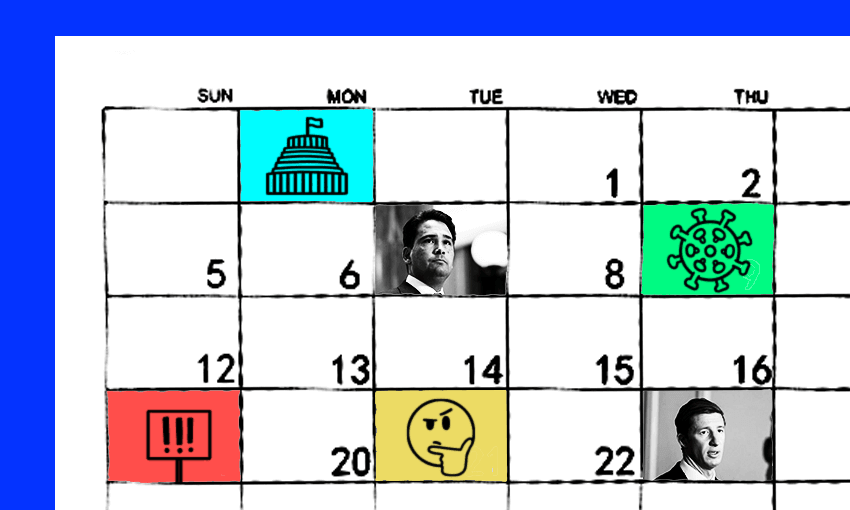

At the tail end of a year that seemed to defy the laws of time, we dust off the dates in the calendar that capture the thing as a whole.

Tuesday March 2: Parliamentary protest ends in flames and violence

Was the pivotal day February 6, when the anti-mandate convoy, inspired by events in Canada, set off from either end of the country? Or February 9, when police attempted to shepherd protesters off parliament – an effort ultimately abandoned, despite arrests, allowing the encampment to bed in? Or Trevor Mallard’s Manilow and sprinkler mini-festival?

It could be any of those, but there is one of the 23 days of parliamentary occupation most deeply engraved in memories: the last. For three weeks, the lawn of parliament had turned into a protest camp and the roads around the complex moats of protest vehicles. Many hundreds of protesters, whose number ranged from the disgruntled and distressed through to the conspiratorial and insurrectionist, were united in anti-vaccine, anti-mandate demands. It ended in violence and fire, with a group igniting gas bottles and tents. There was an attempt to burn down Old Government House.

It was the worst day of ugly division in Aotearoa, but not the last. In the shadow of both the unprecedented disruptions from the pandemic response and the riot at the US Capitol, it set a tone that we haven’t yet fully shaken off.

Monday March 14: Cost of living pressures prompt fuel tax cut

This set a tone, too. No one was debating any longer whether cost of living challenges amounted to a crisis. Fuel prices had surged against a backdrop of Covid-induced supply chain disruption and geopolitical instability stemming from the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Amid that “wicked, perfect storm”, the prime minister announced that cabinet had decided to cut fuel excise by 25 cents a litre. Public transport fares were simultaneously halved. It would all cost more than a billion dollars.

Tuesday March 15: Simon Bridges quits

I had to double-check this one – surely it was earlier than this? But no, there it is, March 15. And the Tauranga byelection that Bridges’ resignation triggered was June 18, which seems even more impossible. In any case, the former National leader’s decision to quit politics to spend more time with his podcasting career (yes, yes, among other things) was a blessing in disguise for his party.

Christopher Luxon’s appointment of Nicola Willis to the finance portfolio Bridges vacated was the best decision he made all year. While Luxon continued to suffer the wobbles through the second half of the year – lapses on detail and a sprinkling of malapropisms – Willis used her many years of political experience (as MP and staffer) to provide some ballast. Grant Robertson has proved a formidable finance minister, but it’s taken this long till he’s encountered someone with the judgment and discipline to give him a proper run for his money.

Tuesday May 31: Jacinda Ardern at the White House

For two pandemic-enforced years from March 2020, Jacinda Ardern’s passport stayed in the drawer. This year it got a workout; from April 18, the prime minister has spent 55 days abroad. Among the summitry, trade delegations, tourism promotion and the big state funeral, the most critical moment was the meeting with President Joe Biden at the White House – the first such visit for a New Zealand PM since John Key in 2014.

It came at a time of geopolitical delicacy. As well as the war in Ukraine, there has been a lot of attention on China’s efforts to grow its influence in the Pacific. In her White House meeting, and in diplomacy since, Ardern has successfully managed to balance relationships with both Beijing and Washington.

Monday June 13: A major minor reshuffle

For all the spin doctors’ efforts to tease a “minor” cabinet reshuffle, this looked major at the time and even major-er in retrospect. Not just because of the personnel shuffling, but the way the announcement (it took Ardern a not-minor seven-and-a-half minutes to get through it) traversed the fault lines the government has confronted across the year – as well as exposing a lack of ministerial depth.

Kris Faafoi had wanted out before the election, but now he was properly escaping, leaving others to clean up policy programmes in various states of shambles – the media merger, the hate speech laws, immigration. He might be about as far from Machiavellian as you could imagine, but he nevertheless would go on to personify New Zealand’s loosey-goosey approach to parliament and lobbying.

Poto Williams was removed from the police portfolio at a time when law and order was roaring into headlines. Ardern put it down to “the narrative”. Williams – who in recent days announced she will stand down at the next election – was replaced with fix-it man Chris Hipkins, but the issue of crime would remain firmly in the foreground for the rest of the year.

Not a minister, but thrown into the announcement mix was the departure of Trevor Mallard’s, moving from the speaker’s chair to a diplomatic seat in Dublin, and ending a remarkable political career that went up and down about as often and sporadically as a Beehive lift.

Sunday July 23: James Shaw voted out of leadership

This took almost everyone by surprise. The Green co-leader was jettisoned from his seat at the party AGM, with more than 25% of the 107 delegates who voted demanding nominations be reopened. Paradoxically, it wasn’t all bad for Shaw and the party, as he packed his knapsack and travelled the country to talk to members. When he came to face his nemesis Ron (reopen nominations) again, Shaw won comfortably – backed by 97% of delegates – which most likely forestalls any internal challenge before the election. It has been a strange old term for the Greens, with a toe in government and the rest outside, but they’ve remained polling close to 10% throughout, which is not a shabby base ahead of election year.

On which point, though I have no obvious day to which to attach it, Act under David Seymour similarly ends the year sitting pretty in polls. Predictions that a dream run would come to a thudding end as National became functional again have been disabused. Another prediction has proved wrong, too. After years of a one-man caucus, the odds on some new MP or other disgracing themselves could hardly have been shorter. The reality is the opposite: a disciplined group, and a number of MPs (among them Brooke van Velden, Nicole McKee and Karen Chhour) emerging as highly competent and values-driven.

Monday August 8: Sam Uffindell’s history of violence revealed

Reports of a vicious high school assault, perpetrated by the newest National MP, Sam Uffindell, shone a light on the party and its processes, on politics and our culture more broadly. The MP for Tauranga was reinstated to caucus after a Maria Dew inquiry failed to substantiate further bullying complaints. Luxon handled the episode as well as could be expected. Just as importantly, the party seems to have sorted some of its selection woes, the evidence of which was best expressed in the Hamilton West byelection. Tama Potaka handsomely won the seat vacated by Gaurav Sharma and seems destined for much greater things than the guy who won the Tauranga edition.

Friday September 9: Queen Elizabeth II dies

This deserves a place in the defining moments of the year not for reasons of sentimentality, but because our literal head of state died and a new one (her son, apparently?) was sworn in.

Monday September 12: Covid lights switched off

Another elastic time mindwarp: it was just a few months ago that the plug was pulled from the traffic light framework and mask wearing requirements went the way of mandates – all (with a tiny handful of exceptions) gone. The year had begun with a third of the country bleary eyed having just emerging from lockdown, and the team of five million was already well splintered. Domestic restrictions and border controls had been loosened across 2022. But this was the day that more than any represented “a return to normal”. Normal, maybe, but certainly not “post-Covid”. The virus is currently killing around three times as many people in New Zealand as does influenza.

Saturday October 8: Local elections

Mayor Wayne Brown might have been interviewed less often than a random Queen Street busker but his victory – comfortable in the end over Labour and Green enforced Efeso Collins – evinced more than anything a disgruntlement with the Direction of Things. It wasn’t quite a triumph for the centre-right, especially in light of Tory Whanau’s Wellington win, but it was broadly a kick in the teeth for incumbency.

The other unmistakable message to central government: people didn’t and don’t like three waters. Also: a bad day for disinformation spruikers, and the turnout of both candidates and voters sucked.

Wednesday November 23: The Orr report

Fans of counting will note that this is the 11th of 10 defining moments. Error? Or a deliberate and clever allusion to the pervasiveness of inflation across our politics in 2023? You decide.

Announcing the last Monetary Policy Committee decision of the year, Reserve Bank governor Adrian Orr put firmly to bed the nonsense that he was somehow in political cahoots with the Labour government. Not only was the base rate going up by a record 75 points, but the outlook for 2023 was, you know, pretty shite. Sticky inflation, the return of unemployment and a gentle dipping of the bow into the (hopefully) shallow waters of recession. It was the day that very much set the scene for election year. See you then.

Follow our politics podcast Gone By Lunchtime on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.