Winston Peters was once the one who could plausibly rail against the self-interest of the establishment. Today that seems laughable, So where are the real critics offering reform, asks Danyl Mclauchlan.

Politics is messy. It’s chaotic; most things happen for complex combinations of reasons and these are not always obvious, and the best explanations you get of why or how things play out are usually pollsters guesstimating effect sizes or pundits dreaming up post-hoc explanations that flatter our own ideas. Hardly anything ever gets validated or proved.

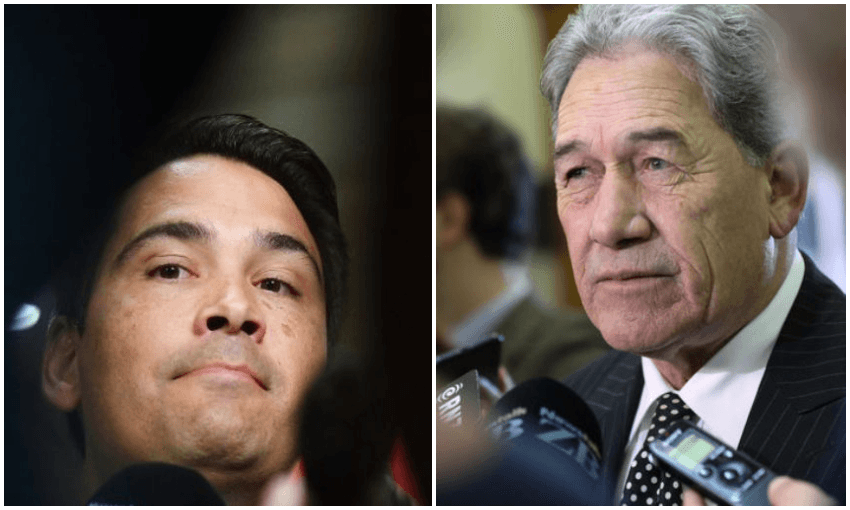

But last week the dark gods of politics seemed to go out of their way to endorse Simon Bridges’ decision to rule out Winston Peters from a future National-led coalition. Bridges has been rewarded with a Serious Fraud Office investigation into the New Zealand First Foundation and more murky allegations around the same foundation showing that it’s been quietly taking donations from the racing industry, while Peters is the sector’s benevolent minister of racing. There have been two polls showing National ahead of Labour and New Zealand First out of parliament, and Bridges is slowly clawing his way up the preferred prime minister ratings.

And Peters himself has rewarded Bridges by performing as the absolute worst version of himself, indulging in classic Peters-style antics, drowning out the prime minister’s electorally vital attempts to remind the voters how much she believes in kindness, forcing her to declare that yes, she still stands by him, absolutely she trusts him, no further comments please; making her look weaker every day.

The prime minister’s problem is that if she stands up to Peters – say, she suspends his portfolio as minister of racing pending the outcome of the SFO investigation – Peters might reciprocate by declaring that he’s the victim of a giant media/business/political conspiracy and that he might not support the government’s budget: maybe he’ll go fishing for a few weeks to think about it. Cue weeks of chaos and uncertainty and breathless media coverage about the prospect of a snap election, with Peters at the centre of it all.

This wouldn’t be a smart thing for Peters to do, but setting up this foundation and then falling out with senior figures in his own party who leaked its details to the media doesn’t look very smart. Nor was volunteering that he was involved in journalists investigating the foundation being photographed. Nor was Peters’ social media announcement this week, in which he promised to clear up all the questions about the foundation, in which the sound was inaudible. None of this is smart.

Which is all good for Simon Bridges. If you’re a swing voter trying to choose between Labour and National you’ll probably base your vote on which party leader you prefer. That’s not going to work out well for Bridges: even some National voters prefer Ardern to him. And it’s hard for a politician to increase their popularity by attacking someone more likeable than they are, because voters tend to give the more likeable, popular person the benefit of the doubt.

So Bridges is attacking extremely unpopular things, like organised crime and the deputy prime minister, targets that his political opponents (sometimes rather bafflingly) support. This redefines the choice architecture for swing voters. Their decision is not “Jacinda versus Simon”, but rather: “Whose side are you on: Simon Bridges or the Mongrel Mob?” Or “Do you prefer a government with Winston Peters’ endless scandal and drama and inane nonsense, or one without?”

Bridges hasn’t defined himself in any positive way. When asked if he’ll reform the country’s laws around political donations, he demurs. When asked about the Serious Fraud Office’s charges against four as-yet-unnamed individuals involving a donation to the National Party, he stresses that neither he nor anyone in his party is among them, and that his fundraising activities are within the law. It’s the sort of thing all politicians say when implicated in a donations scandal. And it’s usually true, but not because they’re pure as the driven snow. It’s because they literally write the laws, and get to decide what is and is not legal, so the laws around political donations have been written with massive loopholes allowing parties to accept large donations and conceal the identity of the donors. You can – if you like – make a $15,000 donation to the party of your choice every year, $45,000 in an electoral cycle (and that’s before you donations go via family members or legal subsidiaries), and there’s no disclosure requirement.

Political insiders often attempt to define the right to make anonymous donations as a freedom, and therefore something that should never be constrained. (Just last week, Peters compared anonymous donations to the secret ballot.) But it is a long-standing principle of liberal political theory that our freedoms conflict with each other: our rights do not fit together like pieces in a jigsaw puzzle. And it seems obvious that the freedom that the richest people, the wealthiest corporations and foreign governments operating through domestic proxies enjoy to anonymously fund our political parties stands in conflict with everyone else’s right to have our country governed in our own interests rather than theirs. The right of companies to secretly fund our political parties in return for policy and taxpayer handouts is not a thing.

There might be some more cosmetic alteration to the electoral finance laws in the wake of this latest series of scandals, but it’s not in the short-term interest of any party in parliament to seriously fix our donation regime. And now, for the first time in a long time there’s no anti-establishment party or figure in parliament critiquing the cozy status quo.

That used to be Winston Peters’ job: he made his name exposing establishment scandals. Several decades ago you could legitimately say of New Zealand politics, “Winston will keep them honest”, without bursting into laughter at the absurdity of the statement. And it made him incredibly popular: in the mid 1990s almost a third of the country named Peters as preferred prime minister (he is currently at 3%). And the Green Party under Russel Norman and Metiria Turei was an anti-establishment party (Turei described it as “an anti-establishment party in the heart of the establishment”), critiquing the security services, the political donation laws, the lobbyists swarming around the last government (and now this one) like bluebottles to a dead cat. This was politically popular – the party once polled as high as 18%, and its internal research showed that as many as a third of New Zealanders were potential green voters. But now the Green Party occupies an ideologically incoherent space bounded by technocratic centrism and campus wokeness, characterised by an obsequious, fawning fear towards Peters and New Zealand First. On current polling it’s not at all certain they’ll be returned to parliament.

But it is in all the parties’ long-term interest to fix our wretched donation laws. Economics lecturers often introduce their undergrad students to game theory by describing how the laws banning cigarette advertising led to a surge in profits for tobacco companies. This was because the advertising was a zero-sum game between the companies. Each company had to spend money on advertising because all the others did. The spending didn’t win them any many new customers, but if they stopped and the others didn’t, they’d lose customers. The spending was pointless – but they all had to do it. It was a coordination problem that no individual player could solve but that was effortlessly solved by the power of the state.

Political funding and political spending work much the same way. None of the billboards that political parties put up every election campaign persuade anyone to vote for that party. But if you don’t put up billboards and all the other parties do, then you probably lose votes. So they all put up billboards, and run print and digital and broadcast campaigns, and invest huge amounts of time fundraising to pay for it all, and it is all mostly pointless. Zero sum. They all do it because it’s a coordination problem that no one inside the game can solve. And there’s no anti-establishment critic to force them to change.

I think there’s a vacuum in our political system. There are obvious problems with the status quo but no real critics offering reform. It’s a situation that Simon Bridges is temporarily taking advantage of, but to which offers no actual, meaningful change. He’ll follow the current laws but since the current laws are designed to be crooked, that doesn’t mean very much.

Lenin used to say that he found power lying on the streets, and simply picked it up. I suspect there’s power lying on the streets in New Zealand politics, waiting for someone to say that our parties shouldn’t be secretly funded by the richest people in the country; that lobbyists shouldn’t be in powerful Beehive jobs, that the country should be governed in our interest, not theirs. And that power is just waiting for someone to pick it up.