Emissions reduction plans, a mandatory part of the Zero Carbon Act, get released every five years. Here’s what we know about the next one.

OK, so… what’s an Emissions Reduction Plan?

New Zealand has made a bunch of promises in international agreements and in the landmark Zero Carbon Act, that aim to reduce our emissions. This goal is broken down into step-by-step emissions budgets, which determine the maximum quantity of greenhouse gas emissions allowed during a five-year period, and are legally binding.

New Zealand’s first emissions budget was set for 2022-2025 – a shorter period, because the legislation had only just come into place. The next two emissions budgets, for 2026-2030 and 2031-2035, have already been set; in general, emissions budgets need to be released a decade in advance so everyone has time to prepare. Set by the government, they’re legally binding, and three (the current one + two future ones) must be in place at all times.

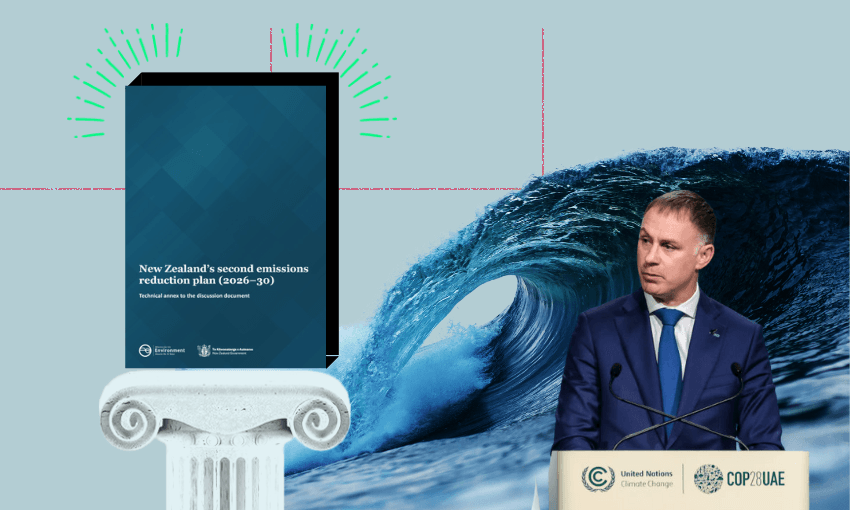

Emissions budgets are accompanied by Emission Reductions Plans (ERP to their friends), which explain the tangible actions the government is taking to meet the emissions budgets. The first ERP was set by the Labour government in 2022. On Wednesday, the government released their discussion documents for the 2026-2030 ERP. The public can read and submit on the plans until August 21. The plan will be finalised by the end of the year.

Got it. So how did we do on the first one?

Well, the good news is that our emissions have decreased slightly: there’s a bit of a delay in processing the data, but we know that in 2022, New Zealand produced the lowest gross emissions of any year in the 21st century, at 78 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. (To put things in perspective, the Ministry for the Environment notes that a tonne of emissions is about equivalent to driving from Auckland to Wellington nine times; multiply that by 78 million to get 78 megatonnes).

In 2023, emissions did increase slightly, partially because of an increase in transport emissions from domestic flights and road freight. (We don’t count international flights in our emissions.)

However, many of the reductions happened because of policies that the previous government put in place, like the Clean Car Discount. Assumptions about future emissions also took into account pledges to eventually incorporate agriculture, our biggest emitter, into the Emissions Trading Scheme, which the National-led coalition has ruled out, and policies like changing speed limits will increase pollution too.

It’ll be a while until we know exactly what impact these policy changes have had on our 2024 emissions, but it’s expected that while progress towards meeting the first ERP will have slowed, we’ll still be within the limits of the emissions budget.

So the government has changed the approach towards the climate – what does this new plan say they are doing?

Simon Watts, the current climate change minister, has said the government is committed to climate change targets. The government has five main pillars for reducing emissions: using “nature-based solutions” (ie planting trees), reinforcing the carbon market, prioritising “abundant and affordable” renewable energy, focusing on “world-leading climate innovation” to enhance the economy and ensuring the “infrastructure is resilient and communities are well prepared.”

In the draft emissions reduction plan, these pillars are emphasised: increasing electric vehicle chargers, improving organic waste processing and landfill gas capture, offering “fair and sustainable” pricing of agricultural emissions and investigating carbon capture and storage (ways to absorb carbon with human-made tools rather than trees).

Based on the estimates the Ministry for the Environment has made, the impact of these policies will keep New Zealand just under the emissions budgets until 2030. However, on current projections, we will not be able to meet our third emissions budget – although the further in the future we go, the more uncertain the estimates are.

The Zero Carbon Act says that reductions in carbon emissions need to come through domestic activities alone – both reducing carbon and absorbing it. Because the current pathway means New Zealand will not be meeting its Paris Agreement commitments through domestic activities, we will probably have to spend billions of dollars to buy international carbon credits. The urgency of increasing tree planting in New Zealand will prioritise faster-growing pine trees over native trees, an approach which has been criticised.

OK, I’m hearing lots of technical language, lots of numbers, lots of predictions. Can you just tell me whether any of it will work?

Different groups and experts have weighed in with their perspectives on the plan. Some emphasised that the plan assumes that technological development will create emissions reductions. Sara Walton, co-director of He Kaupapa Hononga (Otago University’s climate change research network), told the Science Media Centre that while the plan removes barriers to businesses innovating, it doesn’t provide incentives like “the development of enabling policies, investment infrastructure for technology and the appropriate development of markets.”

Geoff Willmott, assistant dean of research at the University of Auckland agreed, saying there was a “predictable lack of ambition when it comes to research and development carried out here in New Zealand.”

Ralph Sims, a professor emeritus of sustainable energy and climate mitigation at Massey University, commented that “many of the [coalition government’s] policies to date will result in higher annual emissions that will not be offset by either planting trees or the emissions reduction scheme” and said that better public understanding of climate science would mean “politicians no longer feel obliged to set policies after being lobbied by high greenhouse gas emitting business that tend to look at their short-term profit rather than long-term prospects.”

Climate activist groups took a more dramatic approach: Adam Currie, of 350 Aotearoa, took a miniature version of the plan to parliament “to demonstrate the incredibly tiny scope of emissions reductions included in the plan.” In a press release, he said “Instead of groping for false solutions, the government should simply support the basic climate actions that we know will slash emissions and create jobs, such as investment in public/active transport, support for community solar, and a phase-out of the dirty fossil fuels that is poisoning our air.”

WWF New Zealand pointed out that the government has ceased funding the Climate Emergency Response Fund and initiatives to help industries decarbonise. “It doesn’t take a climate expert to see that their maths don’t add up. You can’t bin your most effective emissions reduction policies, replace them with nothing of substance, and then expect to see a balanced emissions budget. It’s simply disingenuous,” said CEO Kayla Kingdon-Bebb.

Meanwhile, free market and public policy think tank New Zealand Initiative said the plan’s reliance on the Emissions Trading Scheme was on the right track: “An ETS-led approach is the right approach,” said economist Eric Crampton. However, “[the] government needs to establish credibility that the deadline [for including agricultural emissions in the ETS] will not just be pushed out again in response to sector pressure.”

Remind me again please what the stakes are?

Global heating means the average global temperature has been more than 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels for over a year. New Zealand’s sea temperatures have warmed more than twice as fast as the global average, impacting the entire marine ecosystem. Thousands of homes in Wellington alone are at risk from sea level rise which will make many people’s homes completely uninsurable. Heat related deaths are projected to increase to 51 per year if global heating reaches 2 degrees above pre-industrial levels, and cause 250,000 more deaths around the world by 2030, putting outdoor labourers and the elderly particularly at risk.

Climate change has already killed millions of people and placed many species at risk. The stakes, in other words, couldn’t be higher.