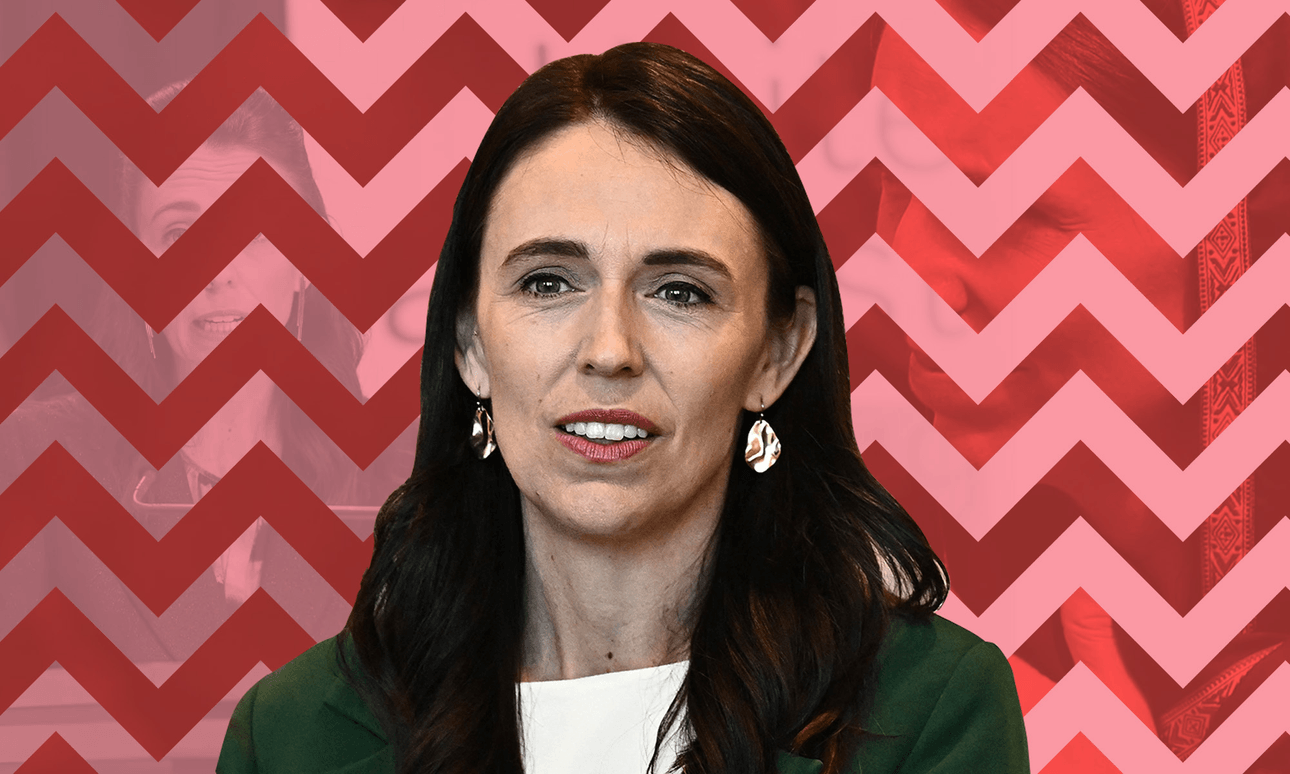

After more than five years as Labour leader and PM, Ardern will stand down before parliament sits in February. What happens next, and how might she be remembered, asks Toby Manhire.

Rumours that Jacinda Ardern might stand down had been circulating for some time, but the announcement of her resignation as Labour leader and prime minister today nevertheless landed as a massive shock. Much like John Key’s announcement in 2016, there was no leak from those in the know. Just this week, I asked a minister who has worked closely with Ardern across the last five years whether she might resign. Not a chance, they said. Never had they met someone with a greater sense of social responsibility than Ardern, came the answer.

At its essence, said Ardern today, was simply running out of gas. The announcement, which overshadowed within seconds another decision – that the election will be on October 14 – came during the party’s caucus retreat. Summer, she said, during what was expected to be a relatively prosaic setpiece just off Marine Parade, had “given me time for reflection”.

Her voice cracking with emotion, she said: “I am entering now my sixth year in office. And for each of those years, I have given my absolute all.” At this point, the eyes of anyone watching started to widen, jaws to drop. This seemed to be going in only one direction. “I believe that leading a country is the most privileged job anyone could ever have, but also one of the more challenging. You cannot, and should not, do it unless you have a full tank, plus, a bit in reserve for those unexpected challenges.”

She had hoped to summon the energy across the break for another election, and another potential term, as prime minister. “I have not been able to do that. And so today, I am announcing that I will not be seeking re-election and that my term as prime minister will conclude no later than the 7th of February.”

Ardern then turned to that word – responsibility. For all the job’s challenges, she said, “I am not leaving because it was hard. Had that been the case I probably would have departed two months into the job. I am leaving because with such a privileged role, comes responsibility. The responsibility to know when you are the right person to lead, and also, when you are not. I know what this job takes, and I know that I no longer have enough in the tank to do it justice. It is that simple.”

Follow Gone By Lunchtime on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.

Where it leaves Labour

She was equally sure, she insisted, that there were “others around me who do”. That is far from obviously the case. In suggesting that this was best for the party, Ardern stretched relentless positivity to breaking point. The timing could have been worse, sure. And there is no use in wearing out an accelerator when there’s no fuel left to burn. But for all that, it is terrible for Labour. Just as Ardern’s arrival as leader transformed the party, her departure risks plunging it back into crisis. At very least, an election that was looking hard for Labour to win now looks desperately hard. The most seamless transition would be to Grant Robertson, the deputy prime minister and finance minister, and one half of the portmanteau Gracinda that once stood as a ticket for leader and deputy. He would not be putting his name forward, however, Ardern announced.

In a statement, he confirmed that. “The level of intensity and commitment required of prime minister is an order of magnitude greater than any other role. It is a job that you must unequivocally want to do in order to do it the justice it deserves,” he said. “I have every confidence that there are colleagues within the caucus who are both capable of doing the role, and have the desire to take it on. They will have my full support.” He stressed that he would run in 2023 for parliament.

Who does that leave? Early favourites include Chris Hipkins and Michael Wood. Kelvin Davis is the deputy leader but has made it clear he has no appetite for the deputy prime ministership, let alone the top job. Kiri Allan? Megan Woods? A history Wood-Woods double act?

Other names may emerge, but time is short. Ardern, who will remain as MP for Mt Albert until April, thereby removing the need for a byelection, implicitly encouraged her colleagues to take advantage of a rule change that means support from two-thirds of caucus obviates the need to commence a full leadership campaign. That vote will take place in just three days, on Sunday. Some, however, will resist such a swift process, pushing for a vote to go to the membership and affiliated unions. Were that to take place, it should be completed by February 7, Ardern said.

While acknowledging that becoming the target of poisonous abuse from disinformation spruikers and conspiracy theorists had taken its own toll, Ardern said that was not the determining factor in her decision.

Just as Key did in his departure, Ardern dismissed any suggestion of ulterior motives. “I know there will be much discussion in the aftermath of this decision as to what the so called ‘real’ reason was. I can tell you, that what I am sharing today is it,” she said. “The only interesting angle you will find is that after going on six years of some big challenges, that I am human. Politicians are human. We give all that we can, for as long as we can, and then it’s time.”

She said: “Beyond that, I have no plan. No next steps. All I know is that whatever I do, I will try and find ways to keep working for New Zealand and that I am looking forward to spending time with my family again – arguably, they are the ones that have sacrificed the most out of all of us.” To which she added a mention for her daughter and partner. “To Neve, Mum is looking forward to being there when you start school this year. And to Clarke, let’s finally get married.”

An extraordinary crisis leader

Ardern departs after five years as prime minister and 15 in parliament. It is too early to make many multiple judgments about her legacy, but few will quibble with the assessment of her leadership in responding to two huge, unimaginable, massively destabilising events.

First, the terrorist attack in Christchurch, a horrific moment in the history of Aotearoa that was met with extraordinary empathy and steel from the prime minister. Second, Covid-19. In the early response especially, Ardern rallied the country to commit to extraordinary actions that for a time made us the envy of the world. Her legacy amounts to much more than that, but those two tower above everything, earning her deserved acclaim around the world.

Ardern’s speech concluded with “a simple thank you to New Zealanders for giving me this opportunity to serve, and to take on what has and will always be the greatest role in my life.” She said: “I hope in return I leave behind a belief that you can be kind, but strong. Empathetic, but decisive. Optimistic, but focused. That you can be your own kind of leader – one that knows when it’s time to go.” After taking questions from media, she exited, emotions welling again, with: “I think we’ll call it a day.”

Follow our politics podcast Gone By Lunchtime on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.