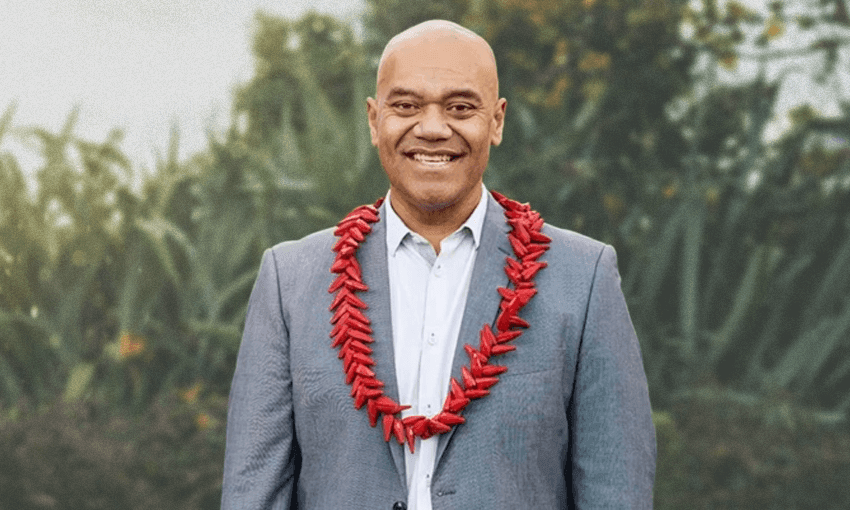

A tribute to Fa’anānā Efeso Collins from Spinoff editor Madeleine Chapman.

There’s this thing that happens when you are a Pacific person doing a public-facing job, which is that you feel immediately familiar with every other Pacific person doing a public-facing job, even if you’ve never met or spoken to them. The bridge to familiarity is short, and becomes nothing the moment you see their face in front of yours and think “oh, of course you get it”.

Fa’anānā Efeso Collins spent his life being a bridge between Pacific people and the whole of Aotearoa. That was his goal, as expressed to me two weeks ago at Waitangi, where he was experiencing the full programme for the first time and loving every second of it.

Being a bridge is not a light ambition to have and Fa’anānā knew that. (Note: A conventional editorial style guide would dictate that I use “Collins” here but Sāmoan custom would suggest his matai/chief title is the most respectful approach. In fact, Collins was an Irish name that Fa’anānā’s father chose shortly before moving to New Zealand, as he thought a Pālagi name would help him fit in better. In this instance I’m choosing to honour Fa’anānā with his bestowed name, from his mother’s village Satufia, Satupa’itea, Savai’i.)

Fa’anānā was unapologetically Sāmoan and Tokelauan, and South Auckland through and through. And his role, as he saw it, was to make New Zealand better understand the needs, wants, concerns and ambitions of both his Pacific and his local communities.

To me, Fa’anānā was the embodiment of the Pacific future in New Zealand. Born and raised in Ōtara to parents who immigrated from Sāmoa in the 60s, Fa’anānā’s beginnings are a walk through the textbook of first generations Sāmoans in New Zealand. His mother Lotomau worked on a factory floor and his father Tauili’ili Sio drove taxis and was, for a time, a Pentecostal pastor.

A childhood spent within the church as the youngest of six children led Fa’anānā to view New Zealand through the lens of Pacific tradition and religion, a lens that is often referenced in New Zealand politics and rarely truly understood. Fa’anānā was not just a part of his community, he helped to shape it. First from within as a youth leader within his church and then as a representative once his interests took him to other areas of Auckland. At the University of Auckland (the first in his family to receive a tertiary education), he got involved with student politics “to ensure better support for our Pacific students” and eventually became the president of the students’ association, the first Pacific person to hold the position.

That pattern, of entering a space, seeing a need for improvement for his people, and becoming the person to make it happen, continued throughout Fa’anānā’s life. He lived in the UK for a short period after university working with youth while on scholarship, but soon returned home to help out his family more directly. And outside the home, his work continued. There were university papers submitted on community development, youth gangs and indigenous education. There was advising the Ministry of Education on Pasifika learning, and the Ministry of Social Development on Pasifika youth development. He hosted segments on Radio 531 PI and Radio Samoa, while writing blog posts for The Daily Blog. Always working, always bridging.

The inevitable move to local politics came in 2013 when he was elected to the Ōtara-Papatoetoe local board, then the progression from local board to Auckland council in 2016 as the councillor for the Manukau ward. It was back then that chatter began about a run for parliament. And along with it came chatter about his range of views.

Like former Labour minister Aupito William Sio, Fa’anānā was a deeply religious man whose views progressed over the years and who was able to speak to his changing perspective, without performatively condemning his past self in the process. After being criticised for statements early in his political career opposing abortion and gay marriage, he changed his stance. In 2022 he said: “It’s my position that I won’t get in the way of women and people who are pregnant making their own, deeply personal decisions. I too am on a journey of understanding and empathy and always open to listening to people’s diverse experiences and beliefs.”

And on marriage equality, he said: “I acknowledge that my position on gay marriage hurt people. I thought at the time that I was really representing the church, standing strong for them. I acknowledge that it hurt people, people who were my friends … I believed, perhaps in a closed-off mind, that it was the only way to express your Christianity. I know today that it’s not the only way to express it.”

As a councillor for six years, he had been supremely annoying for central government and therefore an effective champion for those he represented. He was associated closely with the Labour party but held his own views, often at odds with the party line. He consistently called for the Labour government to grant amnesty to Pacific overstayers and increased those calls during the pandemic when scrutiny and judgment was placed on those wary of submitting their details for Covid testing; he was vocal in his criticism of the Covid-19 response as it pertained to South Auckland and community vulnerabilities therein; and he was a vocal supporter of the Ihumātao protests in 2019.

Politically, his differing views were heard and tolerated by those in power. Other times, his opinions were met with force from strangers. He endured a spate of death threats after he called for TVNZ to retire Police Ten 7, a show which, he said, “feeds on racial stereotypes”. It went beyond the racist hate mail he’d become accustomed to, and police conducted a sweep for explosives in his south Auckland apartment following bomb threats.

“I think that was a pivotal moment for our family,” he said. “As a big Sāmoan guy, I’m used to being challenged. If people come up to me and challenge me, that’s cool. I can have conversations. But I wore quite a deep sense of guilt because I thought I had brought it on my family.”

His family – wife Vasa Fia and two daughters – were in support of his public-facing work. It was only after discussing at length with Fia the implications for putting himself further into the public spotlight, that he decided to enter the race for the Auckland mayoralty. In an interview with the Spinoff announcing his candidacy in early 2022, he said: “We came back thinking we’re kind of the people we are, and even if I was to walk from politics, I would probably end up in a role where I’d still be speaking my mind. I’ve always chosen to speak what I believe in. It was there that we firmed up the decision.”

At his campaign launch, he pointed to priorities including affordable housing, free public transport and climate change. “We want to be bold,” he said. “Let’s dream of an Auckland that’s different.”

A campaign jingle from his local board race in 2013 ‘Efeso, Efeso, Efeso, Yeah, Yeah’, featuring lines like “He grew up in Ōtara, in the hood where life is harder / Efeso Collins is a Polynesian version of Obama”, was revamped for the mayoral contest.

Fa’anānā did not receive a Labour party endorsement for his mayoralty run until late in the piece. Whatever Labour’s reasoning was at the time (and it’s very hard not to assume race and outspokenness played a part in those decisions), it was a failure to support a genuine leader with potential to make huge change to the largest Pacific city in the world.

Following a comprehensive loss in the mayoral elections, and after half a decade of people telling him his perspective was needed in parliament, he joined the Green party in 2023 and became an MP at number 11 on the party list.

But Fa’anānā was not a party man, he was a people man. His concerns were entirely about how best to serve his people, rather than any party, and for a while it seemed he had no interest in advancing his own career beyond his community. In 2017, he spoke of his feelings towards the political system and Pacific leaders within it. “My own people may be unhappy with my views, but I believe that a lot of Pacific politicians have been giving into a system that’s feeding them but that’s not bringing our people forward,” he said. “There’s a whole lot of rhetoric around the rising tide lifting all the boats. But too often the rising tide is only serving white middle-class New Zealand.

“And too often, as our people have been climbing their career ladders, they’ve forgotten about their roots.”

Tragically, we will never find out whether or not Fa’anānā would live up to that principle in parliament, but if I had to guess, I’d be confident in his links back to his past, his fanau and his people. As an MP for only a few months, he was still finding his feet within the political system when I spoke to him at Waitangi a fortnight ago, but was absorbing everything with the intention of passing it back to his Pacific community. We spoke of him being a necessary bridge between Pasifika and Pālagi, but also Pasifika and Māori, who sit closely in negative statistics and apart in political approaches. He pondered a near future where young Pacific people would be standing alongside Māori in fighting for our futures, both socially and environmentally. He considered himself, at 49, the perfect conduit between his parents’ generation of “work hard, head down” and his two daughters’ generation of further education and understanding of Aotearoa history.

The one note in Fa’anānā’s life that looks out of place is the casual mention of him attending Auckland Grammar. As a staunch South Aucklander and Pacific advocate, it read like a deviation in Fa’anānā’s journey. What was the story there? Turns out, his parents had been told by a Pālagi teacher at intermediate that Fa’anānā was “too bright” to be staying in Ōtara for college. So his parents sent in an out of zone application to Auckland Grammar and he was accepted. Suddenly his prospects were much brighter, was the understanding, and the path to individual success was laid out before him.

Fa’anānā lasted two weeks before returning home.

Ia manuia lau malaga, Fa’anānā Efeso Collins.