There is plenty yet to play out, but the next election is at this rate shaping up as trio versus trio, writes Toby Manhire.

A subplot of this week’s historic hīkoi mō te Tiriti has been the sight of the three opposition parties presenting a unified front. Te Pāti Māori took the leading role, while the Greens and Labour stood and spoke alongside them on the steps of parliament. Inside, Labour and the Greens combined to ensure that every question, patsies excepted, related to the Treaty Principles Bill (TPM did not ask a question).

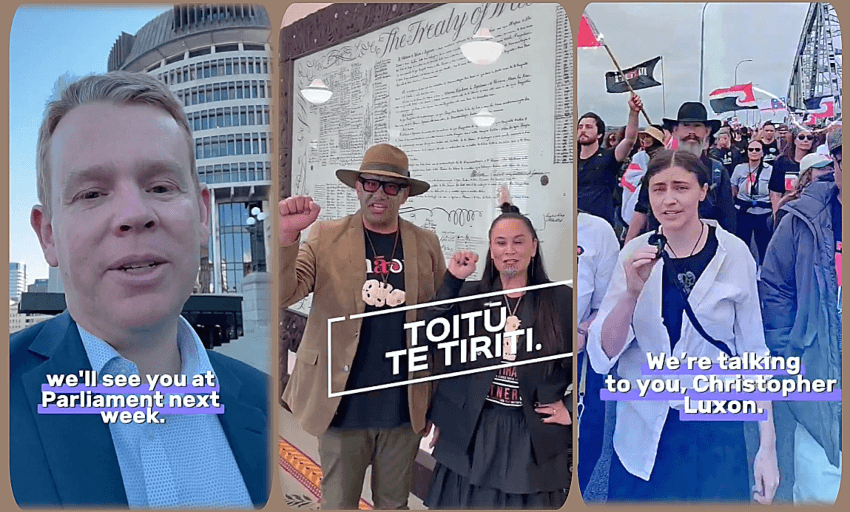

The week before, both Green and Labour MPs stood to haka in parliament after Hana-Rāwhiti Maipi-Clarke had torn the bill in two – an episode that brought New Zealand either great pride or great embarrassment on the global stage, depending who you ask. The three parties also released a video featuring leaders of all three parties promoting the hīkoi. It may not have hit the viral heights of the parliamentary haka, but it sent an effective message: We’re joined up on this.

Interviewed by RNZ on Wednesday morning, Labour leader Chris Hipkins said the opposition parties had “worked very closely” in the lead-up to the protest. “I think we’re very unified on this issue,” he said. “We see it taking New Zealand race relations backwards. I think all three parties are unanimous on that view – we all want to see the bill go.”

They can try to divide us, but we stand united. Toitū Te Tiriti. ❤️💚🖤🤍@NZGreens @Maori_Party pic.twitter.com/p7SYbPBBzT

— New Zealand Labour (@nzlabour) November 14, 2024

The visible camaraderie on the opposition benches paints a marked contrast with the coalition itself, where National MPs have most recently been seen denouncing a bill immediately before voting for it, while Christopher Luxon confronts endless questions about his stance on that bill, whether he erred by cutting a deal to “aerate” such “divisive” ambitions, and, more broadly, if the tails were wagging the dog.

MMP governments in New Zealand have for the most part proved stable, but coalitions are almost always delicate animals. Just look at Germany – the prototype for our own proportional system, where the “traffic light coalition”, the country’s first three-party coalition in more than 60 years, has just collapsed, triggering an early election to be held next February. No doubt David Seymour will be keeping an eye on developments in his downtime: the German government came a cropper after the free-market Free Democratic Party balked at what it saw as a leftward budget. The FDP is of special interest to Seymour – he was so impressed with them when trying to rebuild the Act Party that he borrowed everything from ideas to the colour strip.

Closer to home, for as long as Act and New Zealand First remain above the threshold, it is hard to see either tempted to do an FDP and torpedo the Luxon coalition. If the seams hold through the six months of select committee and the changing of the deputy PM guard from Peters to Seymour in the middle of 2025, chances are the three parties will go into the 2026 election looking more or less like a bloc. There’s plenty of water to go under the bridge before then, but if they can keep the coalition intact, the government parties will swing that same spotlight eagerly on the alternative trinity. Remember the blunt metaphors and “pretty legal” soundtracked National rowing ads? Remember John Key’s “devil-beast” rhetoric? All that and more.

The messy fudge around the Treaty Principles Bill – in base political terms, a gift to both Act and Te Pāti Māori – will unavoidably direct even more attention than usual at the next election to questions of bottom lines and rulings-out. Sorry, but it will. On both sides. As one commentator put it before the last election, “Smaller parties need to be careful in whatever they issue in terms of bottom lines or they could find themselves simply not able to be part of any governing arrangement at all because, ultimately, the larger parties do need to be able to implement the commitments that they campaign on.” That commentator was Chris Hipkins, and it was greeted by TPM co-leader Rawiri Waititi as tantamount to “oppression”. He said: “You don’t tell indigenous peoples what our bottom lines are.”

However constructive the cooperation in repelling David Seymour’s bill might be, therefore, that is a picnic compared to what awaits. Any shot Labour might have of restricting Luxon’s government to a single term will surely be dependent on forming a government with TPM support, as well as the Greens. Expect Hipkins – should he lead Labour into the election – to spend a lot of time talking about the Greens, and even more about Te Pāti Māori. Is withdrawal from the Five Eyes alliance a bottom line? Is the establishment of a Māori parliament? Does he go along with the latest example of histrionic rhetoric?

Te Pāti Māori today is so squarely – and successfully – rooted in an activist, anti-establishment ethos it is hard to imagine it joining a formal governing coalition at all. Māori Party support for John Key’s National governments came with ministerial responsibilities but not a place in cabinet and the current party – in some crucial ways very different from that earlier version – may feel more comfortable similarly located. But even were that signalled early on, it brings the imprimatur of coalescence.

For its part, National will be quietly but keenly seeking to build its support such that it might divest itself of one of its coalition partners and return to government with greater leverage. It is very hard to imagine New Zealand First (or Labour for that matter) swivelling sufficiently back into territory where they could repeat a 2017-style deal with Labour. And while a panicky National in the days before the last election sought to raise the alarm over NZ First, it’s unlikely to do that next time. In the lead-up to that election, meanwhile, David Seymour and Winston Peters were involved in a protracted flamewar. A relapse is always possible, but they’ve so far managed to hold together a novel marriage of convenience.

All of which means, unless there is some serious shakeup in opinion polls or inter-party positioning, the 2026 election is increasingly shaping up to be something we haven’t seen before – a contest of two blocs, three versus three, complete with the catchcry: your coalition is more chaotic than mine.