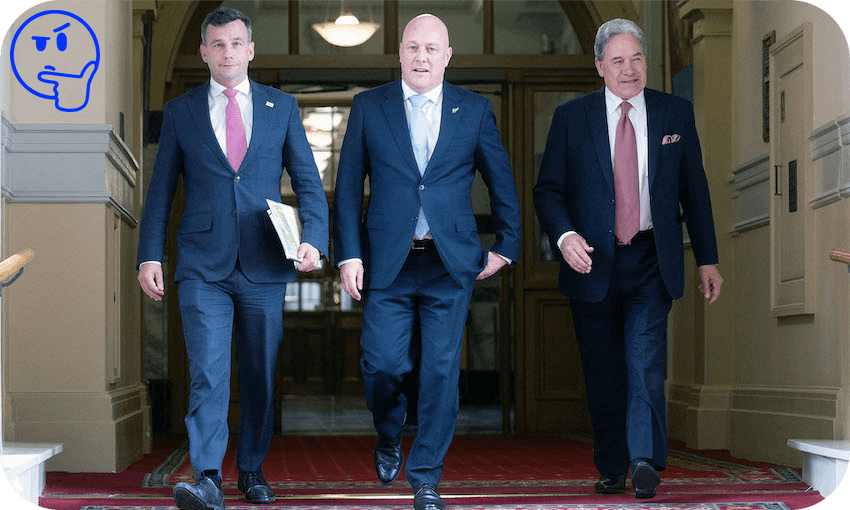

After some ‘interpretative cross-checking’ of the coalition agreements, constitutional law expert Andrew Geddis sees confusion in this government’s future.

The two documents that set the basis for our new Three-Way coalition government are a bit of a lawyer’s delight. National has agreed a whole bunch of stuff with Act. National has agreed a whole bunch of stuff with New Zealand First. Act and New Zealand First haven’t directly agreed anything with each other, but they have promised that they’ll each support what they understand the other to have agreed with National. Two written documents that each contain extensive detail across a wide range of issues and so seek to capture the intentions of three different groups of people. What is also known as “a disputant’s goldmine”.

Nevertheless, what then have the three parties apparently cooked up between themselves? Putting aside all the boiler-plate “we’re pulling together for a brighter future” material, working out the actual content requires quite a bit of interpretative cross-checking. Basically, the starting point is all those things set out in (deep breath) National’s eight-point commitment card, fiscal plan, tax plan, 100-day plan, and 100-point economic plan. These matters are now deemed to be coalition government policy – except where either of the agreement documents diverge from them, that is.

Meaning that you have to go through all National’s various policy commitments as set out at election time, cross check them with both the National-Act agreement and the National-New Zealand First agreement, and where there’s no express difference, then they still stand. But if there is some divergence, then the position as set out in (either) the National-Act or National-New Zealand First agreement stands. On top of which, both Act and New Zealand First have some of their own policies expressly accepted by National in each of the separate agreements (which are then, in turn, accepted by the other party in our new gouvernement à trois arrangement).

Which is to say, it’s all a bit complicated and is going to take a while for all the details to get fully digested. Even then, some confusion is going to reign. For example, the National-New Zealand First agreement unequivocally states that the new government will “ensure, as a matter of urgency in establishment and completion, a full scale, wide ranging, independent inquiry conducted publicly with local and international experts, into how the Covid pandemic was handled in New Zealand … .” However, the National-Act agreement only commits to “broaden[ing] the terms of reference of the Royal Commission into the Covid-19 response, subject to public consultation”. These are not the same thing at all, yet apparently both are now official government policy that all three parties are committed to.

There’s a bit of similar fudge when it comes to one of the obvious hot-button areas for the coalition partners – what to do about te Tiriti and “strengthening democracy” (to use the language adopted in both of the agreements). Here, it seems clear that the three partners were more in agreement about what they didn’t want than what they did. No more “co-governance in the delivery of public services”. No more delivering public services based on “race” instead of “need”, including getting as granular as requiring a review of how people get selected to enter medical school. No more guaranteed Māori representation in local government, unless the non-Māori residents of the area vote to allow it.

But how the new government plans to unpick te Tiriti’s role in our wider constitutional arrangements is less clear. Act’s once-upon-a-time bottom line of a referendum on what “the principles of the Treaty” ought to mean is watered down into a promise that legislation allowing such a vote will get sent to a select committee (with the clear implication being that it then goes no further). New Zealand First wins a promise of “a comprehensive review of all legislation … that includes ‘The Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi’ and replace all such references with specific words relating to the relevance and application of the Treaty, or repeal the references.” That sounds grand and overarching, but how will it sit with Supreme Court dicta stating that the way Treaty principle provisions are worded in legislation doesn’t really matter … and that you probably don’t even need them anyway, given how much te Tiriti is a part of our constitutional fabric?

All of which leaves a lot to be fought over (hopefully ideologically and politically, rather than literally) in the next three years. We’re going to have to work out what the relationship is between “race” and “need” is in a society where pervasive structural disadvantage creates unequal outcomes. We’re going to have to question the extent to which temporary parliamentary majorities can alter constitutional presumptions that have been developed over some three decades prior. That is, if there really even is a parliamentary majority in favour of some particular change.

Oh – one last thing. The parties have all committed to legislation setting up a referendum on moving to a four-year parliamentary term. I’m putting my money down now that the outcome of this referendum will depend on how the public reacts to the coalition seeking to deliver on this combined agreement over the next three years. If they can make it work, it’ll probably pass. But if it all falls apart, then it won’t. Let’s see where we end up.