A cancelled meeting in the Pacific raises larger questions about aid, climate change and the role of China and the US in the world’s biggest ocean.

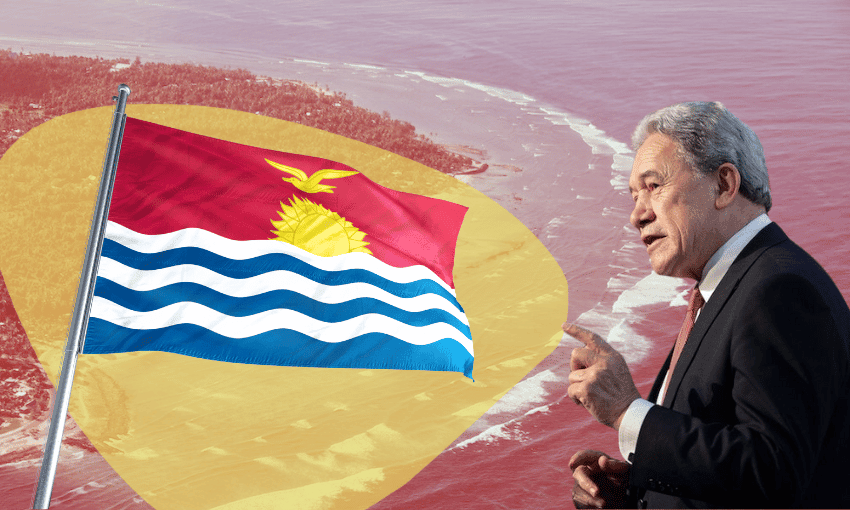

New Zealand is reviewing its aid for Kiribati after the president of the Pacific country declined to meet with foreign minister Winston Peters. What’s the context of this diplomatic disagreement, and who will it affect? Here’s a quick background.

Where is Kiribati?

Kiribati, pronounced Kir-i-bas, is about 4,000 kilometres directly north of New Zealand. This Pacific Island country is made up of 33 small islands across three million square kilometres of ocean, the world’s 12th biggest exclusive economic zone and filled with valuable fisheries. There are 107,000 I-Kiribati people on the islands – more than Tonga, but about half the population of Sāmoa. Kiribati has one of the lowest GDPs of any Pacific Island country, and receives different kinds of overseas money: direct aid, fishing licences, working remittance schemes and a small amount of tourism. Foreign assistance was about 32% of its gross national income in 2022.

Banaba, a coral island that is part of Kiribati, was extensively mined for phosphate during the 20th century, with residents deported to Fiji. The phosphate fertiliser was sold to different countries, particularly New Zealand, Australia and the UK, which jointly owned the mining company responsible. The phosphate was almost all gone, with extensive environmental damage and only 10% of the island’s surface left, by the time Kiribati gained independence from the UK in 1979.

OK, so New Zealand played a role in the colonisation of Kiribati. What’s New Zealand’s relationship been with the country since it gained independence?

New Zealand has given significant amounts of international aid to Kiribati, more than $300 million since 2010, and $53 million in the 2023/2024 financial year. A lot of this money has been targeted towards climate change adaptation, as Kiribati is just 1.8 metres above sea level on average, and salination of water, coastal erosion and smaller fish stocks put people living there at risk.

New Zealand is one of the few countries with a full embassy in Tarawa, Kiribati’s capital, which opened in 1989. It grants “Pacific access” residency visas to some Kiribati residents each year, and Kiribati citizens can come and work in New Zealand’s horticulture industry under the RSE scheme, doing work like thinning apples and picking kiwifruit.

(Photo by Jonas Gratzer/LightRocket via Getty Images)

Sounds like an ongoing relationship of New Zealand acting on its responsibilities to poorer nearby countries. So what has just happened with Winston Peters?

Barbara Dreaver, 1News’ Pacific correspondent, reported that foreign minister Winston Peters had been trying to arrange a meeting with Kiribati president Taneti Maamau for a year. Peters was finally set to visit this month, marking the first official visit in five years. The two government representatives were going to discuss a $25m hospital upgrade New Zealand aid had paid for, as well as seasonal workers, on January 21 and 22.

A few days before, however, the New Zealand embassy in Tarawa was told that the president was no longer available, but Peters could meet vice-president Teuea Toatu instead. After the difficulty arranging a meeting, this was interpreted as a “diplomatic affront”. Australia was offered the same arrangement, but unlike Peters, Australian deputy prime minister Richard Marles chose to meet with Toatu.

In response, the New Zealand government has said it needs assurances that the Kiribati government is actually committed to a relationship with New Zealand in order to continue the air programme, which is now under review. “The lack of political-level contact makes it very difficult for us to agree joint priorities for our development programme, and to ensure that it is well targeted and delivers good value for money,” a spokesperson from Peters’ office told RNZ.

So to remove the diplomatic language, New Zealand gives Kiribati lots of money, and is now frustrated that Kiribati doesn’t want to talk to it about future plans. Given that New Zealand is a major partner, why is Kiribati doing this?

It’s worth noting, first, that Kiribati’s education minister Alexander Teabo has said the denied meeting wasn’t an intentional snub, but a calendar clash: Maamau had to attend an important event on his home island. Most reporting around New Zealand and Kiribati links this shift to Kiribati’s relationship with China. Like several other Pacific countries, Kiribati recognised Taiwan as an independent country until 2019, and in return received more aid and support from Taiwan. In 2019, Kiribati decided to recognise China instead, which now has an embassy in Tarawa. Taiwan said that China had offered Kiribati aeroplanes and boats to switch allegiances.

Since being recognised, China has committed more than $107m to Kiribati, funding disaster resilience, student travel to China and money for new boats and jetties.

There are always people talking about China having too much power in the Pacific – are those fears actually well-founded? Or just a way to implicitly say that New Zealand, Australia and the US don’t like not being the only big powers in the Pacific?

Ah yes, the question every small country eventually runs up against: does “upholding the rules-based international order” just mean “keeping the American superpower happy”?

Foreign policy experts like Marco de Jong have pointed out that the idea of New Zealand’s “traditional partners” being the US, UK and Australia doesn’t fit with a Pacific-centred view. Emphasising China as a threat to the Pacific and using this as a reason to have more military interventions like Aukus could “create the instability it’s professing to address”, de Jong told Te Ao Māori News in May.

While it seems subtle, the New Zealand decision to review Kiribati’s aid funding following the diplomatic incident shows that New Zealand expects Kiribati to keep engaging with Western donor countries. Meanwhile, Jon Fraenkel, a Victoria University of Wellington comparative politics professor, told RNZ that revising funding “usually works in the reverse direction, to kind of push countries away rather than draw them in”. He pointed out that a decision from the New Zealand government might simply remind Kiribati that it “does have alternatives, both in China and elsewhere”.