Its first season made waves and earned international accolades. Rūrangi director Max Currie tells Sam Brooks what’s changed for the second visit back to the small town.

When Rūrangi was released as part of the New Zealand Film Festival in 2019, nobody really knew how far the film would go. It was bracing, fresh and earnest, focussing on Caz (Elz Carrad), who returns to his hometown for the first time since transitioning. It received warm reviews, and then a second life when it was edited into a six-part web series which was later broadcast on Neon (where it’s still available).

It wasn’t just what was onscreen that made the film special; it was made with both of the communities that featured in it in mind, especially the trans community. Over half of the cast and crew on that initial production were non-binary, all trans characters were played by trans actors, and there was an advisory panel of trans people who had veto power over the production.

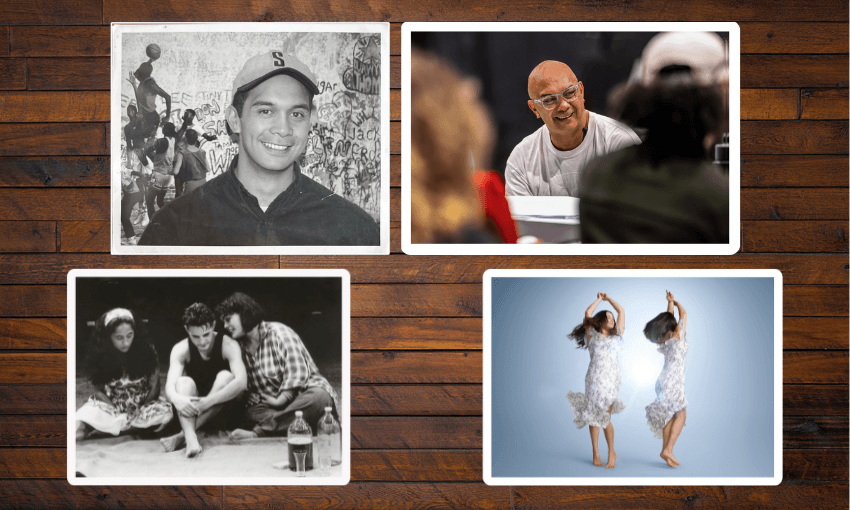

Since then, the series has been picked up globally (on Hulu in the US) and won an International Emmy for Short Form Series as well as a slew of local awards. It was a certifiable hit, so prominent that Elz Carrad featured as a guest judge on RuPaul’s Drag Race Down Under, and director Max Currie featured as a member of the show’s Pit Crew.

The second series expands on the world of Rūrangi substantially. Not only do we see more of the town, especially the struggles between the tangata whenua and the Pākehā administration that does everything to ignore the effects of colonisation, but we also see more of the life that Caz has left behind, or run away from, in Auckland. The show is bigger, better, and richer.

The first thing Currie and the team did when they received funding for the second season was to actually go to Ngātea, on the Hauraki plains: literally re-entering the world of Rūrangi. They met with locals ranging from city councillors, to farmers, to the entertaining personalities at the pub that every town seems to have. “There was a real joy and a real excitement to physically go back there,” Currie says. “It was important to share the space with our broader team of writers because we had more resources this time around, and could have more people involved.”

As a result, Rūrangi feels less like Caz’s story, and more like the story of the town; the ensemble is not just larger by number, but their individual characters are beefed up too. This was in response to audience feedback. “What we kept hearing after season one was that people wanted more of everything – more of Anahera, more of Jem – and we asked ourselves what the show would look like if we took an ensemble approach?”

From there, the idea of looking at “where the trouble began” came together – as in, when did regressive and hateful ideas about gender and sexuality begin to infiltrate New Zealand? Anahera (a stand-out Āwhina-Rose Ashby) became the central character to interrogate this, during flashback sequences that could almost be dreams; Anahera’s ancestor suddenly finds herself outcast from her iwi, which has repercussions that linger towards the modern day.

What makes Rūrangi stand out, especially in a television landscape that is still struggling with meaningful representation, is how neither of the communities depicted in the series feel slighted. Both tangata whenua and the trans community are represented thoughtfully, even-handedly, with equal amounts dramatic heft and relatable humour.

He singles out Craig Gainsborough, the series’ lead producer, for laying down that alternative way of making the series – where everybody had some sort of a say, or the ability to speak up if necessary. “His decisions were really about giving power to other people, which is terrifying when you’re the creative,” he says. “What do you mean we’re having a panel of intersectional, gender-diverse people who have never written television before, who also have actual veto power?”

As the second season expanded to more explicitly deal with te ao Māori, it was important for them to get their support system for the tangata whenua working on the series up to the same level as the one for transgender people. “I don’t think you can explore these tensions without reflecting on them within the group of people who are making it,” he says, referring to the writing team of Briar Grace-Smith (a new addition for season two, who directed half of the season and served as co-showrunner), Cole Meyers, Awa Puna, Aroha Awarau, Victor Rodger and himself. “The writing was very collaborative. We read each other’s work, we re-wrote each other’s work, we discussed the work together. The idea of having many perspectives and many experiences moving forward together, that’s what happened in the writing in a way.”

He credits Grace-Smith with a lot of the humour in the second season, especially. “If we’re going to stick our fingers in our national wound, I think we have this obligation to make people laugh and to play along with us,” he says. “Briar has brought that in spades, and we both still crack up watching the second season.”

The production took a lot of care around the use of Te Reo in the show, especially when it was and wasn’t subtitled. It led to a lot of conversations about the gaze of the show – who were they centering? Who were they othering? – and that extended to use of te reo Māori. As it is, Rūrangi is one of the more fluid New Zealand shows; characters slip between languages without any fuss, and even New Zealanders least versed in Te Reo will probably be able to fill in the gaps without the need of subtitles.

The care, and the thought, has paid off. Rūrangi doesn’t look, sound, or feel like any other show on TV, here or overseas. Meaningful representation is impressive, but representation that reflects the messy collisions of intersectionality with heart and humour is a downright miracle.