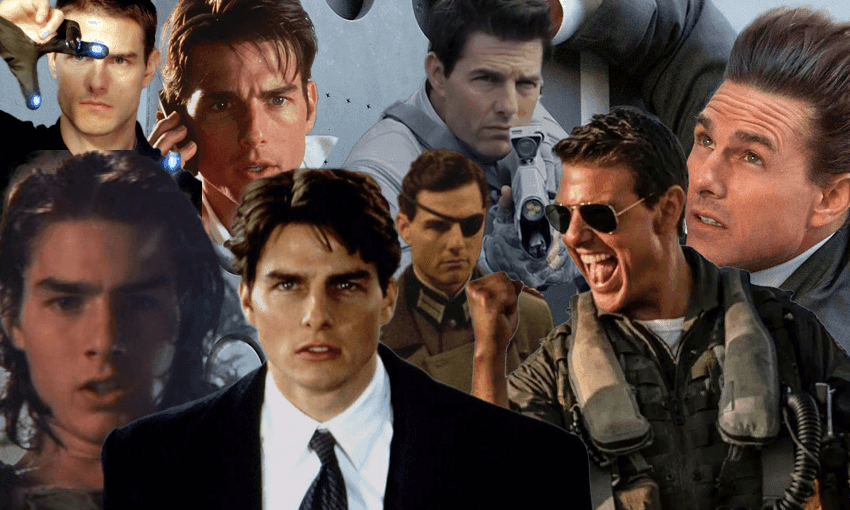

I watched all 46 of Tom Cruise’s films over the past 12 months. The question on everyone’s lips: why?

The Spinoff Essay showcases the best essayists in Aotearoa, on topics big and small. Made possible by the generous support of our members.

Over the last year, I’ve watched every single Tom Cruise movie ever made. In my head – and aloud while drinking wine – I called it the Thomas Cruise Completionist Project. Everyone else just called it stupid.

Like any self-respecting dumb project one inflicts upon themselves and is held to by absolutely no one, there were rules. The 46 movies had to be watched in chronological order. I had to watch at least one every two weeks, but preferably every week, and I had to take notes: where I was, who I was with, what I thought. No skips, even if I’d seen it before or was absolutely dreading it, because who would want to watch a movie called The Last Samurai starring a white guy (Cruise, naturally) that came out in 2005?

Universally upon finding out about this project, everyone asked why. Tom Cruise is weird! True. He is short! I do not discriminate against the short, but true. He is in a cult! Damningly true. He is a thrice-married adrenaline junkie whose cousin is randomly in Lost! All true. Why do this at all?

Well, for the bit, obviously. Does no one do things for the bit anymore? What is the cornerstone of our national psyche if not being sincerely dedicated to pissing about? If I am not committed to the bit I am committed to nothing. Also, I finished my Master’s degree and needed a project to stay sane while job hunting.

Tom Cruise has been a movie star for what feels like all time, but actually since about 1983. His whole career is sort of unbelievable, but when you experience it week by week it feels destined, even sublime. His film debut is the near unwatchable Endless Love (1981), which my flatmate Soph and I watched while she ate an unbearably salty pasta and Tom ran around in denim booty shorts and indirectly inspired arson.

From there he’s on the periphery of a few films: some good (Taps, The Outsiders) and some completely horrendous (if a worse movie was made in 1983 than Losin’ It, my best mate Siân and I owe everyone worldwide $5).

But it was film five that made him; jetted him up and apart. Risky Business (1983) – watched alone, job hunting with a freshly shattered laptop, wretchedly miserable – is a movie star’s movie. Slick and exciting, you can see exactly why it blew the doors off the place in the 80s. He slides into his living room, white shirt, long socks, singing into that candlestick, and even though it’s Tom Cruise and he’s as familiar and canonised as the Coke logo, I still believe him: he is not a future film star but a teenager, left home alone, about to be very stupid to impress a girl.

From there, he was a rocket. If you can name an adored, white, male director in the last 50 years, Tom Cruise has probably worked with him: Michael Mann, Martin Scorsese, Ron Howard, Stanley Kubrick, Oliver Stone, Steven Spielberg, Rob Reiner, Cameron Crowe, Paul Thomas Anderson, and on and on. Notably, you can count on one hand the number of female and/or directors of colour he has worked with.

In 1992, he set up a film production company with his former manager Paula Wagner, and they essentially produced every movie he made for the next 14 years. He is renowned for exerting a remarkable level of creative control and interest, which most famously means he does a lot of his own increasingly insane stunts.

You can essentially trace the evolution of contemporary film trends, and the health of the wider industry, through the movies Tom Cruise can get made. In the 80s and 90s, he’ll try anything, any genre. Interesting script with a lot of main character screen time and a promising director attached? Thomas Cruise Is On The Phone.

He’s in a string of critically beloved classics, which I have ranked in the following order of watchability: A Few Good Men (1992), the Colour of Money (1986), Rainman (1988), Fourth of July (1989) and (please do not watch this movie, it’s ghastly) Cocktail (1988). He was rightfully nominated for his second Best Actor Oscar in 1997 for starring in the romantic comedy/sport drama – seriously, it does everything – Jerry McGuire (1997), which finally got two of my friends on the Tom Train, though I think this was only because at the outset Tom says: “I had so much to say and no one to listen”, and my friend Ami immediately turned and said, “Wow, he’s just like Caroline”, which the room found indescribably funny.

Even the bad movies are often at least ambitiously bad. I have nothing but respect for Eyes Wide Shut (1999), a film my mate Katie still refers to as “Eyes Wide Boredom”, for swinging for the fences and getting weird with it. Legend (1985), Days of Thunder (1990), Far and Away (1992) are all bad but at least vaguely watchable, and not even just because Nicole Kidman is in half of those and it’s nice to see her. They’re all original stories, even the contemporary ones rendered period pieces by virtue of time; full of beautiful people and bizarre plots. He is nothing if not committed to that Irish accent in Far and Away (1992); me and the girls were beside ourselves. It is equal parts indefensible and inspired.

It is hard to hold this fact in your head, but Cruise originally became famous because he was very good at his job. Before he was Tom Cruise: The Institution, he was Tom Cruise: Good Actor. There’s a moment in Mission: Impossible 2 (2000) where you can tell, within a second, that the person on screen is the villain in a Tom Cruise mask, and not the real Ethan Hunt aka Tom Cruise (there’s no time to explain) just from the look on his face: mean and hard and wrong. Over and over again, Cruise is the best part of the movies he’s in. Flashes of that assured, attuned kid in Risky Business sliding around in his tube socks, so good that he jets right into the A-list actor stratosphere and never comes back down.

Something in his work shifts in the 2000s, though it’s hard to identify at first. He’s still in massive original movies with huge directors, but they peter out over the decade, with the stunners fewer and farther between. Vanilla Sky (2001), The Last Samurai (2003) and War of the Worlds (2005) all do not land for varying reasons. Lions for Lambs (2007) and Valkyrie (2008) are films made for long-suffering high school history classes.

There are still highs: at the turn of the century, Cruise stars as a misogynist, Tony Robbins-type in Magnolia (1999). He says, into the camera, “Respect the cock and tame the cunt”, which made my sister reflexively say, “Good lord”. Minority Report (2002) and Collateral (2004) are also two supremely thrilling movies, directed by greats. Notably, he makes a foray into comedy with Tropic Thunder (2008), which, with deepest apologies to every boy ever, I did not like, though Siân and I both agreed Tom was funny in it before we put the J-Lo documentary on. Regardless, the decade as a whole is awkward and stilted, and Cruise looks much more at home in the 90s.

The 2000s are also when Tom Cruise gets publicly Quite Weird. He becomes the face of Scientology, jumps on Oprah’s couch, declares that postpartum depression is just being a bit bummed out, and thereby burns the bridge to normalcy.

This specific type of infamy does make it harder for him to disappear into characters, and it shows. This is not to say he isn’t great during this time, because he is, but as my project went on, it became increasingly funny to watch Tom Cruise walk around on screen being called things that are very obviously not his name. He does two movies where he’s a Vincent, and one where he’s a Mitch, and both of these are fine. But Ray? Jasper? Brian? Be serious. Tom Cruise is not called Brian. In Days of Thunder he is called Cole Trickle and everyone involved should be embarrassed by this. While watching every movie, no matter what his character’s name was, all my mates called him Tom.

But if Tom’s 2000s are weird but still watchable, the 2010s are just depressing. Mostly because the movies he used to make (exciting screenplay, big budget, huge director) are fading from existence. Auteurs who may have once flocked to film are now being enticed away by television, and movies have all but surrendered to the franchise machine. Of the films he is in over this time, Knight and Day (2010) is terrible, American Made (2017) and Rock of Ages (2012) are both passable, and Edge of Tomorrow (2014) is astounding and all of us deserve suffering for letting it flop financially.

It is in the 2010s that he makes the worst movie of his career, the irredeemable corporate slush that is The Mummy (2017). Deepest apologies to Laura for having to watch it with me and even deeper apologies for briefly falling asleep. The movie is only interesting for its transparent desperation: Tom Cruise trying to create his own Marvel universe to avoid joining the one that already exists.

That said, if you don’t want to forfeit creative control to the Disney overlords, why not just go all in on the superhero franchise you’ve already been making for 20 years? Ah yes, the Mission: Impossible series, which Tom starred in through the 2000s, only for them to truly come into their own in the 2010s. Even the stellar Top Gun: Maverick (2020) is essentially a Mission: Impossible movie – meaty stunts, big leaps, unreal shots – but gayer.

Years ago, my friend Shannon said, “For God’s sake, the mission is clearly possible” – and she was right, but only because Tom was there proving it. As his peers flocked to the small screen, Tom Cruise remained without a single acting television credit.

Cruise has a reverence for thrilling, precise blockbusters, and so the Mission: Impossible franchise is really the perfect summation of his 50-year career. He’ll go anywhere, do anything, to keep you looking. Or, as my flatmate Mamata put it as we watched him scale a building in Mission: Impossible (1996): “He does so many activities.”

I finished my project while visiting my parents, where we watched the fitting final film, the pithily titled Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One (2023). The first time I watched this movie was more than a year previously, when it was first released, and I dragged several long-suffering friends to the cinema. Mamata pulled out a packed lunch at the halfway mark, Sophie unceremoniously fell asleep, Will repeatedly told me to shut up, and I drunkenly left my phone in the cinema and made Ami drive me back to The Embassy the next morning.

This time around, I still ended up defending the three-hour runtime (it builds!) while my mum repeatedly said Tom should let himself go a little grey, and my dad required the entire plot explained back to him scene to scene yet still claimed at the end to have enjoyed it. In a way, Tom and I ended up right back where we started.

Really, I’ve buried the lede on why I did all of this. I have loved the Cruise Classics (the first few Mission: Impossibles, the original Top Gun) since I was a child, because my father did not believe in democracy when it came to picking movies. He raised my sister, brother and me on everything he loved. The politically indefensible, movie-length military commercial that is Top Gun (1986) is the essential background to most of my childhood, constant as the radio in my mother’s car or my brother’s voice in the backseat. I was destined to love Tom Cruise, that brilliant freak, all my life. We cannot help what makes us.

You must notice too, when you read this, how the people I love were always there during my project. I watched many of these movies by myself, but I ended up watching more with my friends and family. Dragging them into my inane effort, come hell or high water. Talking with Siân about how All the Right Moves offers genuinely good class commentary. Telling Laura she was ageist after she screamed objectively too loud when the old butler showed up in Eyes Wide Shut. Sitting in the bright, doctor’s-office lighting of Ella’s old apartment, screaming at the slow-motion bullets in Mission: Impossible 2. Surrounded by moving boxes with Soph and Josh, laughing about Vanilla Sky. Trying to ignore Jack Reacher while Ami and I get ready on the floor of the new flat. Hijacking a drinks at Ethan’s with Edge of Tomorrow, and hearing Hamish say it’s just like that Adam Sandler movie Fifty First Dates, and it’s not, but no one can stop laughing long enough to tell him.

This project was sheer joy and love and lunacy. Gold proof, obvious and forever, of the care and patience of the people who love me.

I could keep going on about this. I have many pointless Tom Cruise opinions that have no purpose but to disturb strangers in bars, or for me to tell you here. But ultimately, the point of the Thomas Cruise Completionist Project is very simple, and Tom would agree: you should watch a movie tonight with someone you love.