Sylvia Giles watches the mid-2000s soap The L Word and discovers a plethora of feminist conversations that are only starting to happen now in the mainstream.

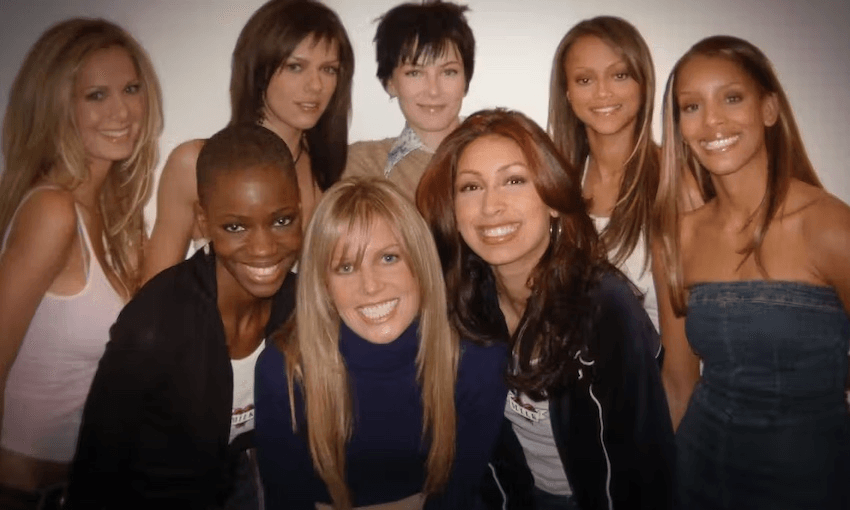

All my lesbian friends told me I should watch The L Word many, many times, and over a decade ago. First aired in 2004, the show chronicled the sapphic adventures of a group of mostly lesbian-identifying friends in L.A – talking, laughing, loving, breathing; fighting, fucking, crying, drinking (etc, etc… as the theme song goes…) their way through six enormously entertaining seasons.

The show wasn’t without its critics – especially from within the LGBTQI+ community, more of which I’ll link to later as their criticisms are more valid than mine. But when I recently binge watched it, 13 years after its initial release, time and time again I saw examples of how The L Word was having fourth-wave feminist conversations that are only now stepping into the mainstream (‘mainstream’ being the operative word – there was, of course, a lot of extremely important feminist work going on at this time, but largely out of the spotlight.)

If you’ll allow me to illustrate…

1) Banishing the male gaze (S4E5)

Remember 2004, when “girl-on-girl action” was increasingly visible in the mainstream, but mostly in FHM and Loaded? The L Word banished, and at times actively criticised, that laddish leer from the outset. They don’t use the phrase male gaze per say, but it’s just notably, refreshingly and totally absent.

My favourite quip is in season four: Alice is dating Phyllis Kroll (played by Cybill Shepherd, who I can only really think of as Cybill Shepherd), who is newly out and also happens to be the boss of Alice’s bestie, and former lover, Bette (this is, after all, a soap.) On returning to Alice’s apartment after a night out, Cybill Shepherd says “I couldn’t believe that guy, he couldn’t stop hitting on us!”

Alice returns: “Oh, that’s typical of a guy: sees two women together, thinks he’s so needed.”

2) Not doing people’s emotional labour, especially blokes’ (S2E10)

In season two, Shane and Jenny need a flatmate, and in walks Mark, a rookie filmmaker who gets the bright idea to shoot a documentary about his lesbian roommates (refer to the aforementioned male gaze). When the bomb drops that he set up hidden cameras across the house to film his flatmates – including their sexual liaisons – without their consent, the fallout ricochets through multiple episodes.

When caught, Mark feebly protests that the project has made him a better man. “Fuck off, it’s not my job to make you a better man,” Jenny replies. Later, when he skulks into the kitchen to return his house keys, Jenny says to him: “you’ve opened up this Pandora’s Box, and now you’re just running away. So I dare you to stay here and deal with this.”

OK, so she doesn’t use the exact words emotional labour, but it’s years before pieces like this one (in 2015) from Guardian writer Rose Hackman, which called for a revolution against this generally unpaid and unfairly distributed work. Mark hangs around for the last few of episodes of the season, then mysteriously disappears and no one even references his having left.

A portent for the patriarchy? One can only hope! Next!

3) Let’s not make this about everyone’s junk (S5E01)

Moira comes to the tight-knit group of friends via a relationship with Jenny in season three but unlike most of the gang, sits outside a static gender binary. She at first identifies as a butch lesbian (which was rare on the show) but soon decided to transition to male. The storyline was criticised for a number of extremely valid reasons, including oversimplifying gender transition (Max takes a T shot, and has a beard in a few episodes’ time) and being flip about the issue of black market hormones.

In season five, having hormonally transitioned, Max decides not to have top surgery. “I felt enough of a guy as is, without the surgery,” he explains to Cybill Shepherd one day, a nod to the variety of ways people choose to transition. (Later, Max revisits this decision.)

Yes, The Vagina Monologues was a groundbreaking piece of theatre for its time, but this is not about anatomy anymore.

4) Non-monogamy (S4E08)

Relatively speaking, society has condoned non-monogamy for men to some degree or another, and even when it hasn’t always been socially acceptable they’ve practiced it anyway. It is much more interesting when discussed in terms of releasing women from the monopolisation of their affections, time and emotional labour, no matter who that is with.

It gets various mentions here and there in The L Word, percolating throughout the show, but becomes a substantial theme in season four when Bette, who struggles with fidelity in monogamous partnerships, instead struggles with the fact her new flame doesn’t do monogamy.

Having been at something of a passionate, tortured impasse for several episodes, they have one tidy conversation and all that tension suddenly evaporates. They go on to have a monogamous relationship without really discussing anything. But I guess that’s the Hollywood treatment for you. Next!

5) Male privilege, or indeed any kind of privilege (S4E6)

Max is working at some L.A. tech company when his colleague Megan is overlooked for a promotion, which goes instead to a male colleague who plays golf with the boss. Max, at this stage presenting and passing as male, tells her to sue her boss: “Nobody deserves that promotion more than you.” Megan replies: “That’s easy for you to say. You’re a member of the boy’s club. A nice member, but a member nonetheless.”

Again, they don’t use the actual words male privilege and it is very complex in this instance – the audience knows Max is trans while his workplace does not. But this aired in 2007. Mainstream discussions took much longer to talk about the flipside of racism; how privilege, like racism, follows you around down the street, into job interviews, at policing checkpoints and so on.

In the end, Max visits senior management to tell them he knows Meg’s boss routinely discriminates against women. He can prove it because when he first interviewed for his job (as Moira) he was passed over for the same role he was later given as Max. It’s one in a million ways in which Max demonstrates himself to be the least self-involved of the crew, with the biggest heart and the truest moral compass (I love Max).

6) Diversity and intersectionality

The L Word was rightly criticised for portraying mostly very femme, lipstick lesbians, although the show wove more diversity into its fabric by its end. In the core cast is Bette, who identifies as biracial. When she and her white long-term partner Tina have a child – with Tina carrying and an African American donor as to reflect the heritage of both women – bit characters often tell Tina she doesn’t “look like” Angelica’s mother, like Bette does.

As well as being trans, Max’s working-class background often means he struggles to connect with the other women (notably he can’t understand what passes as a salad in L.A.). Carmen, the Latino DJ, is not out to her Catholic parents, and military police officer Tasha, who is black, is fighting the US army’s “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy (we are in the Bush years, although this storyline resonates under the current administration too).

I’m not the person, as a cis straight white woman, to say whether these storylines were done well or not; other vastly more qualified and queer writers have already done so here, here and here. The show didn’t specifically explore how race, class, disability, gender and sexuality specifically layer upon each other to different effect, but maybe it’s a bit rough to measure a 13-year-old show by contemporary yardsticks (although intersectionality was born of scholar and activist Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989; this long incubation period has been due to resistance from white feminism until the last few years).

But given so much has changed in the realm of women’s issues since then (the surge in popularity of mainstream feminism, the election of Trump and subsequent 2017 Women’s March, the incredible turn of events where Harvey Weinstein suddenly galvanised public opinion on sexual assault and harassment), and The L World‘s knack for canny “show, don’t tell” storylines like the above, the upcoming reboot will be a very interesting one to watch indeed.

Click here to watch all six seasons of The L Word on Lightbox: