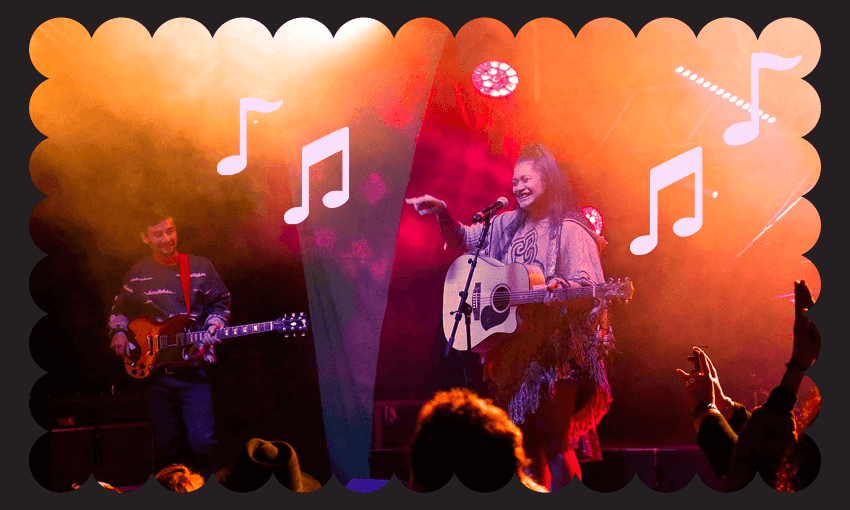

Big breaks and crushing lows feed the music of Sāmoan singer/songwriter Mema Wilda. She talks to Sela Jane Hopgood about magic, space muffins and the places music has taken her.

The garden, I notice, is very well maintained. I meet Mema Wilda at her front door. She invites me inside and seats me at the dining room table while her husband Clint brings us coffees and their two cats vie for my attention. I ask, “Is Wilda a Sāmoan name?” and she laughs, not quite answering my question, but explaining, “I love unicorns and I love magic, and Wilda is like an untamed black unicorn that does its own thing, which I think is fitting for me.”

Born Vaimoana Tumema Sesega-Peters, Wilda started singing at unpaid family gigs, then moved up to weddings and Sāmoan functions and has now created an entire musical persona with, undoubtedly, a touch of the magical unicorn about it. A captivating singer who dabbles in various genres, from folk to funk and rock, the tone of her voice is smooth like Brooke Fraser’s yet when projected is more reminiscent of Boh Runga.

Wilda moved to Tāmaki Makaurau from Sāmoa late 2017, unemployed and wanting to find a better life for her aiga, which includes her Clint and their two sons.

Her first gig in Aotearoa was at the unlikely venue of Junk and Disorderly — a store selling antiques and collectibles in Balmoral, Auckland. But it didn’t take long for people to hear the magic, and Wilda started getting gigs at places like the Samoa Business Network Awards. Before long you could catch her at venues (and sometimes weekend markets) across Tāmaki Makaurau, and then there were the festivals: Okura Forest, Mood Indigo, Resolution NYE, Earth Beat and Cross Street Music. Wilda started opening for bigger acts: Ben Catley, Alec Randles and White Chapel Jak. And earlier this year, she was a part of the Auckland Music in the Parks online offering to the locked-down city.

Most memorable so far, she says, was at the Queens Wharf for the Ports of Auckland Seeport Festival a couple of years ago. “I’ve always wanted to perform on the main stage there and so when the event manager offered me the opportunity, I thought she was messing with me.” Wilda was initially going to perform with three other band members, but once she was confirmed for the main stage, she had a couple of days to string together a bigger band. And so, she did, managing to pull together a seven-piece band to take the stage in front of 10,000 people.

The thrill of performing in front of a massive crowd was something Wilda yearned to feel again. Last year she and her friends began planning to tour the country, but lacked funds. “Our drummer suggested we enter Battle of the Bands because one of the prizes was a New Zealand tour,” she says. It wasn’t smooth sailing though. The competition was postponed due to Covid-19 restrictions. When Wilda and her band eventually made it to the finals, filled with confidence, they discovered that their bass player was a complete no-show. They competed anyway and – to Wilda’s shock and delight – she was named the winner of the 2021 Battle of the Bands. The prize package was invaluable: a performance at Rhythm and Vines, recording time at the LAB in Auckland and with mixing in Australia by Steve James, an Allen & Heath mixing desk and other Audio-Technica and Jansen prizes.

It was a big break – although not Wilda’s first. She’s been chasing opportunities for longer than she’s lived in Aotearoa. When she was 17, long-standing actress, writer and producer Pamela Stephenson-Connolly visited Sāmoa to start a TV talent show, auditioning people to form a band. Wilda auditioned, but the show didn’t end up going ahead. “When they closed up production, she approached me and asked if I wanted to go with her to New York to pursue music. I was so overwhelmed by the request, I spoke to my parents, and they were sceptical, but they let me try it out.”

The Sāmoan teen headed for NYC. “Of course, I got homesick,” she laughs.

“After staying a week with Pamela, she left me with an American couple who were very lovely, and we moved to Los Angeles. I remember being at a big dinner party. The couple had put me, a Sāmoan girl who ate meat every day, on a vegetarian diet, so the food at the party was foreign to me,” she says. “I was offered chocolate muffins and I thought, finally, some yummy food. It actually tasted strange. I assumed, OK, well everything I’ve had so far tonight tasted weird, so this is no different, and I put three muffins on my plate.”

Wilda’s friends noticed she was acting strangely. “I was laughing more than usual and then I started crying and it didn’t help that my friends were looking at me weirdly, so that triggered me to cry more. After sleeping it off, my friends told me they were in fact ‘space muffins’ filled with cannabis.” Wilda flew back to Sāmoa shortly after with a music contract that she needed an adult to sign, but she decided to not return to the US. “I met my husband when I came home, so I’m grateful for that.”

In Sāmoa, church songs are heard everywhere, yet Wilda shares that growing up she listened to The Beatles, because that was her late father’s favourite band, and Simon & Garfunkel. Recently she’s been enjoying Pearl Jam lead singer Eddie Vedder. “I love that I can never understand what he’s saying or the words that he uses, yet I can feel the emotions behind it, the sadness and the pain. I feel like my songs are along those same lines,” she says.

Wilda describes her single, How I Long, released last year as a love letter to herself following a dark period during lockdown, which brought out a lot of unhealed trauma from her past. “I was self-sabotaging myself with alcohol, masking up the pain I was bottling up and it was affecting my family,” she says, tears welling in her eyes. “One day I called the ambulance because I felt like I was going to die. I had a severe panic attack, where I couldn’t see clearly through my left eye and my heartbeat sounded so loud that I couldn’t hear anyone else talking.”

Wilda was admitted to a mental health clinic where she was supported with ways to unpack her feelings and, with the help of medication, she was able to understand the problems she was facing. “There’s a lot of free help out there when it comes to our mental health and my journey has made me realise that the art of my music stems from the traumatic experiences I’ve been through.” The trauma feeds the music and, Wilda hopes, the music feeds others facing their own trauma. “Simply by letting people who are going through similar journeys know that I understand.”

She points to the window and that garden I noticed saying, “The garden you walked past is one of my new hobbies. It has helped with my mental health, giving me the peaceful space I need to grow, just like the plants.”

This is Public Interest Journalism funded through NZ On Air.