Alex Casey talks to director Josephine Stewart-Te Whiu about finding just the right amount of light in the darkness.

One of the most memorable scenes in We Were Dangerous was never in the script. It takes place in a classroom on Te Motu, the island outpost for “incorrigible and delinquent girls”, where a faded portrait of Queen Elizabeth and sign scolding ENGLISH ONLY loom over the proceedings. Thankfully, nobody seems to take much notice, loudly thumping their fists, chanting joyfully in te reo Māori, and throwing pūkana at each other across the circle.

As it turns out, the young actors had been playing the clapping game between takes to try and stay warm. “They were doing it with such high energy,” recalls director Josephine Stewart-Te Whiu (Ngāpuhi, Te Rarawa). “I was just like, ‘I have to put this in the film’.” Thanks to a handheld camera and an extra half hour, they managed to squeeze it in, a scene that now sits alongside many moments of rebelliousness and joy inside an oppressive patriarchal and colonial system.

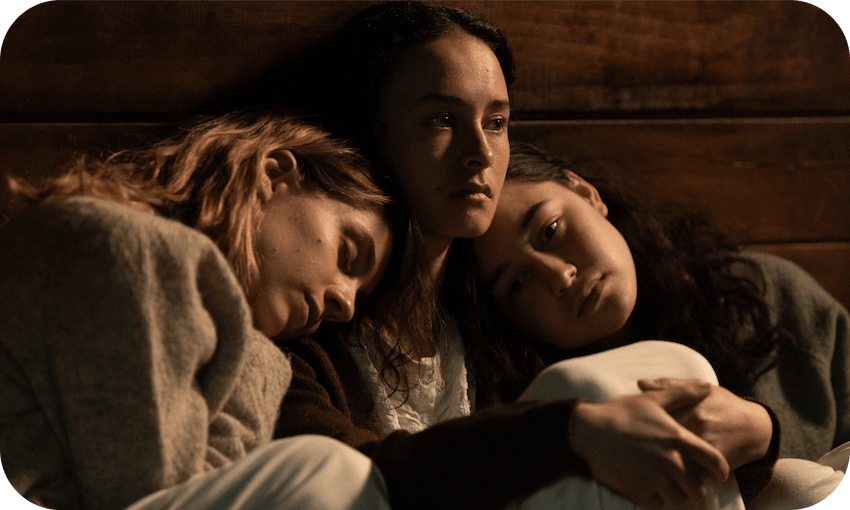

Set in 1954, We Were Dangerous follows trio of friends Nellie (Erana James), Daisy (Manaia Hall) and Lou (Nathalie Morris) as they plot to bring down that very same system from within. Living under the thumb of the tyrannical Matron (Rima Te Wiata), the girls’ resistance initially comes in small acts – pulling faces and making jokes, heaping mattresses onto floor and scheming all night. But as the dark truth of the island is slowly revealed, they are forced to consider a more dramatic course of action.

Although the events of We Were Dangerous are fictional, much of the film feels as if it could be lifted straight from our history books. Writer Maddie Dai drew from real documents such as The Fertility of the Unfit, in which politician and doctor W.A. Chapple called for the sterilisation of those with “mental, moral and physical impairments”, and The Mazengarb Report, which anguished over juvenile delinquency in the 1950s being a result of contraceptives and female promiscuity.

More resonant still are the parts of the film that confront institutional violence, the premiere of the film coinciding, entirely by chance, with the release of the Abuse in Care report. Stewart-Te Whiu is more than aware of the timing, and is wary of the comparison. “Not to take anything away from the inquiry at all, but it was never our intention to make a film about abuse in care,” she says. “We wanted to make a film about young women being their whole selves.”

That said, the darkness at the heart of the film was always there, and Stewart-Te Whiu says it was a challenge to balance with the comedic moments that naturally arise in a coming-of-age story. “I didn’t want to get stuck into the cinema of unease, but I also didn’t want to get stuck in the copying Taika [Waititi] buzz,” she laughs. “I think there’s always a bit of pressure to emulate that style of comedy in New Zealand, and you really need to work hard to make it your own.”

Through the rehearsal process, it became clear to Stewart-Te Whiu that the humour would come from the friendship between the girls and their interactions with The Matron. “The key was that The Matron couldn’t know she was funny – she had to play it straight. And Rima obviously nailed it.” Aside from the three main leads, all the other girls in the film were Christchurch locals who had only done the odd play before. “They were all just such a joy and a delight,” she says.

What also gives the film a remarkable lightness of touch is the cinematography, capturing both the intimacy and expansiveness of adolescence in close-up candlelit giggles and wide outdoor shots of girls lounging in the golden grass. “I tend to get inspired more when I’m filmmaking from photography and art,” says Stewart-Te Whiu. before dropping some reference images from Japanese photographer Osamu Yokonami into the Zoom chat box.

“He was obsessed with the ways that you lose your sense of self when you wear a uniform,” she says. “I was really inspired by that whole juxtaposition of what was inside them, which was wild and free and pissed off, but then they’re confined by the uniformity of all having to look a certain way.” The Banks Peninsula offered the perfect rugged backdrop – the bare land, long-stripped of any native trees, also adding another subtle allusion to the themes of colonisation.

It was another Yokonami-inspired shot that is Stewart-Te Whiu’s most memorable. “There’s a shot of the girls all just lying in the grass after a day’s work.” She recalls having five minutes and one chance to get the shot at the end of a long day. “When you’re working with kids, you can’t go overtime, so my cinematographer sprinted up the hill and I had to corral the actors while she got the camera ready. It ended up being my favourite shot of the whole film.”

The final ingredient in Stewart-Te Whiu’s secret sauce was the edit. German editor Hansjörg Weißbrich was brought in at a point where she says the film felt tonally “stuck” and was a vital pair of fresh eyes. “It felt scary to bring in an international voice on something that is inherently very New Zealand,” she says. “But it made a huge difference, because he was not affiliated at all with the politics of our filmmaking, and just stayed character-focused and story-focused.”

It seems all of those choices have paid off, as We Were Dangerous received the Special Jury Award for Filmmaking at South by Southwest Earlier in the year (Stewart-Te Whiu came home with a large belt buckle as a prize). Critics have since praised the “roaring light” of camaraderie that “cuts through the darkness”, how the film “effortlessly tackles dark subject matter with a light touch”, with some suggesting the “upbeat tone as a rousing show of defiance unto itself.”

“We set out to make a film about young women being playful in their bodies, sometimes even a bit grotesque, and just being humans,” says Stewart-Te Whiu. “It’s really a celebration of girlhood and that time in your life.” With that said, she wants “everyone in the whole world” to see it. “I think that it’s accessible for everyone, because it’s really a story about people who are on the outside and pissed off at the system,” she laughs. “I think we’ve all felt that.”

We Were Dangerous is out now in cinemas nationwide.