It’s one of New Zealand’s biggest gaming success stories, played by a million people around the world every day. On the 10th anniversary of Path of Exile, Sam Brooks finds the game is still going strong.

Auckland’s Aotea Centre was fitted out like never before. The massive windows that look out towards Queen Street were blacked out, and a dry ice haze pumped through all three floors of the labyrinthian space. Huge screens with fantasy characters loomed over replicas of similarly fantastical artefacts.

This is a venue that hosts big events. Conferences with people in identical suits. Operas with six-figure budgets. Festivals for both readers and writers. But for one weekend in July, it hosted an event dedicated to a video game: Path of Exile.

As I sat in the Kiri Te Kanawa Theatre, full from the front row right up to the circle with people in black hoodies, clutching tote bags emblazoned with “Exilecon 2023”, on their laps, I wondered if the dame herself had ever heard of this game. Most New Zealanders probably haven’t.

Which is odd, because not only is the game made right here in New Zealand, by New Zealanders, it’s one of the biggest success stories in gaming in the past decade.

The journey to Path of Exile actually started well over a decade ago. Grinding Gears Games, founded and still based in Auckland, was then just a small group of role-playing game enthusiasts who wanted to develop a game of their own. After three years of development, helmed by lead designer Chris Wilson, they announced the game in September 2010. Their inspirations included the Diablo series, Dungeon Siege, Magic: The Gathering, Guild Wars and Final Fantasy. (If that list doesn’t give you an idea of what the game looks and feels like, you may not be its target audience, sorry.)

Path of Exile leans towards the darker side of fantasy, taking place on a desolate continent where an island nation exiles people, which also happens to be home to many ancient gods and ruins. Players can choose one of several classes – think Dungeons and Dragons if you’re lost – and fight their way back to Oriath, either by themselves or alongside other players from across the world.

Between its announcement in 2010 and its full release in October 2013, meaning the release of version 1.0.0, Path of Exile became its own phenomenon, picking up loyal fans who provided feedback through the development process. One of the core goals of the game was to provide a free-to-play game financed solely by “ethical microtransactions” – essentially players could pay for cosmetic items, but the game never engaged with the lootbox trend that was looming at the time.

By the start of 2013, before it had been properly released, Parth of Exile received over $2m in crowd-sourced contributions. It was clear: this game was a big deal, and people actually wanted to play it.

Upon its full release, the game was an immediate success, not just among audiences but also critically. It was named the 2013 PC Game of the Year by GameSpot, up against a list of heavy hitters, and best PC role-playing game by IGN in the same year. Less than six months after its release, it had five million registered players – more than the population of New Zealand at the time. In 2018, tech giant Tencent became a majority holder in GGG, a huge step for the company. Seven years later, in 2020, it won the award for Best Evolving Game at the British Academy Games Award, arguably the world’s leading game awards.

As the 10 year anniversary of the official launch of the game passed just this weekend, it maintained over a million daily players, spiking every time a release pack is released.

So what keeps people playing it, more than a decade on?

Longevity was always in the cards for Path of Exile, according to lead designer and managing director of GGG, Chris Wilson. “We were aiming to make what we call a lifestyle game,” he says. “One that could be something people would play for a very long time. They could learn the systems, master the gameplay, and take it with them for the rest of their life.”

This, obviously, informed the way that GGG developed the game. It had to be something that people would come back to, frequently. “They’d be a Path of Exile player,” says Wilson. He also points out that it’s good from a business point of view, because you get customers not just across a release window, but over their entire lifetime.

To enable this, Path of Exile implemented a 13-week cycle. Every 13 weeks – so roughly every quarter – the company would release a new update for the game. These updates could include everything from new characters, new gameplay modes, new skins for pre-existing characters and rebalancing of mechanics designed to fix what might have been broken (in a gameplay sense) and rein in what might be overpowered. The latest update, Trials of the Ancestors, released just a few weeks after ExileCon, includes all of these.

Wilson notes, however, that while the 13-week cycle does get players coming back, they often don’t stick around for that entire time. “Players often have their month of playing Path of Exile really hard, looking forward to a fresh start and beating other players,” he says. “Then they get their couple of months off, they play other games, catch up on TV, see their friends in real life, before they’re sucked back into the next expansion.”

Through this pacing, the company “lets players live their life” between releases. “It creates that longevity, because they know there’s another Path of Exile release coming,” he adds. “And if they miss that, they can just come back three months later, for the following one. It makes it very easy to maintain a long-term relationship with the players.”

That cycle, now a part of the Path of Exile experience, wasn’t an immediate development. When the game was first released, it was obvious that people liked it, from both the reviews and the amount of players they had.

“Then players started to leave, and we weren’t used to that fact yet,” he says. After each release they would stay for a number of weeks, and then drop off. It was “horrifying” for the developers to watch the players leave, and they worried they would have to settle on a relatively low number of players.

“It was only when we’d done a cycle that we realised that this was going to work for the long term,” he says. “The relationship was that we would release expansions that the players would play for a period of time before taking a break and coming back for the next expansion.”

The fanbase is, like many in the gaming sphere, a double-edged sword, but one that Wilson ultimately finds helpful. “If we do something great, they’ll be our biggest evangelist and our biggest advocates on the internet,” he says. “But if we do something they don’t like, they’ll be very quick to let us know.”

“It cuts both ways.”

The company’s relationship with New Zealand is a fascinating one. The country doesn’t make up a whole lot of the worldwide gaming market (0.6%), but because GGG is based here, it is important to them. “We do stuff in New Zealand because it’s our local jurisdiction, and it’s very cost-effective for us to do it,” he says. “But if it were somewhere we weren’t living, we wouldn’t put a special focus on it. It’s only that it’s near and dear to us.”

A lot of local gamers they interact with are not even aware the game is made in New Zealand, even though the company has an outsized presence here, and much of both the cast and creative team behind the game are New Zealanders. Despite the game’s popularity, and the size of both ExileCons, neither have received any local coverage either. “It doesn’t bother us, and it’s not important for us to market the game in that way, but we were a little surprised considering the scale of the event.”

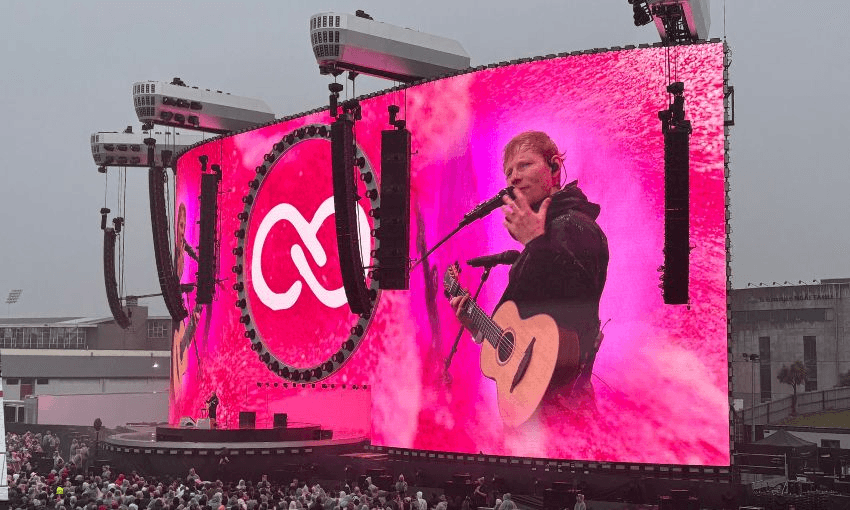

Back in July, in the Kiri Te Kanawa Theatre, Wilson walked out onstage to rapturous applause. The cameras on either side of the audience swung around to capture his every move, every word, watched by thousands more eager Path of Exile fans across the world. He was followed by Jonathan Rogers, talking over gameplay of the long-awaited sequel (announced in 2019, out in June 2024). I later realised that I went to primary school with the guy who ends up playing the demo of Path of Exile 2.

Even as an experienced gamer, sitting in the audience of the keynote session often felt like watching a foreign language film with the subtitles turned off. The crowd erupted into applause at moments that I couldn’t parse – the mention of 1500 passive skills generated especially loud whoops. The phrase “press spacebar at any point to roll, no cooldown” was received so vocally that I felt like I was in an evangelical church, listening to an especially uproarious sermon. A young man a few seats along from me, sitting by himself, was especially vocal during the gameplay demonstration, with little desire to contain himself. Why would he? He was in an audience of his peers.

The true scale of the event didn’t hit me until after the keynote speech, though. Less than 10 minutes after the speech was over, nearly every PC in the building – and we’re talking dozens, scores here – had someone on it, clicking away at the demo build of Path of Exile 2. Hundreds more attendees stood in line for merch, exclusively available at the convention. Downstairs, streamers discussed the keynote speech, being beamed to thousands of people across the world.

ExileCon is a very humbling experience for Wilson – meeting people in person, and seeing the faces of players. “So many people will introduce their wives and explain, ‘We met playing your game and got married with a wedding themed around Path of Exile!’”

“Obviously, there’s selection bias – the type of players that come to an in-person event in New Zealand to meet us are obviously the biggest fans, but those fans are really lovely.”

The convention makes the success feel real, obviously. These aren’t numbers on a screen, these are people in a real space, meeting each other, and bonding over a game that has ten years of goodwill in its favour.

It was way back in 2010 that Path of Exile started to feel real for Wilson, though. The company had just had a server set up to play the game locally, and were still a year away from being announced, 13 away from being a decade-long success. The developers had invited friends and family to play the beta. “They all logged in, and they started to take it really seriously – trading items, grinding through the game. We saw them taking it really seriously as an actual game.”

“That’s the moment when we realised all we needed to do was polish this, dump a lot of players on it, and they’ll have a blast.”