As omicron continues to surge it’s easy to feel defeatist about your chances of staying ahead of Covid. But ‘let it rip’ still isn’t the answer, as two experts on viral outbreaks explain.

Aotearoa New Zealand has entered new Covid territory, characterised by high vaccination rates but also the rapid spread of the omicron variant and rising numbers of hospitalisations.

As we approach the peak of this wave, some have suggested it would be better to drop remaining public health measures, let the infection rip through our population and accept nearly all of us will get infected very soon. This is unwise for many reasons.

First, simple measures we can all take will ensure that even in this big wave of infections, most of us can still avoid getting infected. Even if you share a household with an infected person, international studies show the risk of catching the virus is somewhere between 15% and 50%.

Second, not all infections are equal.

The delta variant is still circulating and we can’t presume all infections are omicron. While less virulent than delta, omicron can nevertheless cause severe disease and death, particularly among the unvaccinated who make up 3% of the vaccine-eligible population but 19.4% of hospitalisations.

There are still many vulnerable people in the community we can protect by limiting the spread of the virus and ensuring they are less likely to encounter it.

Another reason to limit potentially infectious contact is that infection is more likely if an individual is exposed to a higher initial dose of the virus. An infection avoided or delayed is always a win as we move closer to even more effective vaccines and improved medical treatments for Covid.

Why outbreaks come in waves

The reason we get large wave-like outbreaks that rise and fall quickly is because the virus becomes less able to find people to infect as the outbreak progresses. Crucially, this happens before everyone is infected.

This is related to the R number epidemiologists talk about. R0 is the average number of people an infectious person infects at the start of an outbreak. When R is greater than one, the number of cases increases, when it is below one, it decreases.

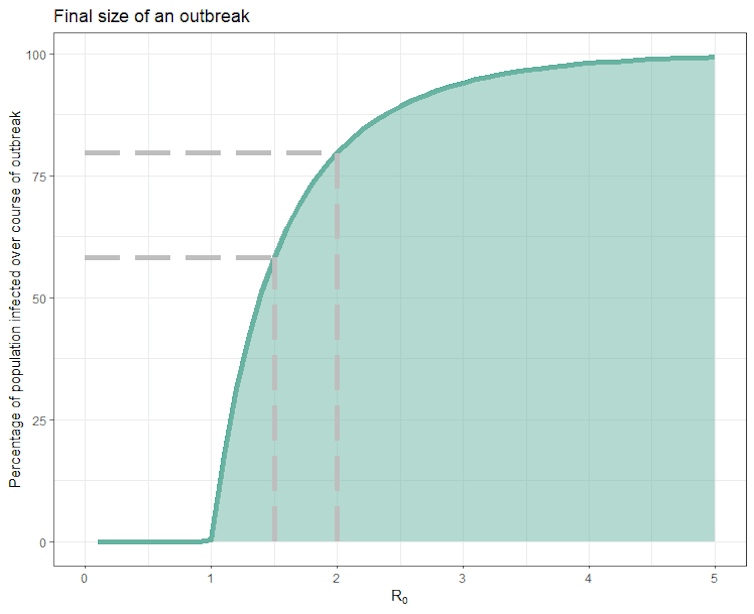

As the outbreak proceeds, more and more people get infected and recover. They cannot immediately be reinfected. For example, if R is 2 at the start of an outbreak, meaning each case on average transmits to two others, by the time half of the population has been infected and has recovered, the virus will only transmit to one other.

That is because it “tries” to infect two people but finds that, on average, one has already recovered and cannot be reinfected. In this example, the R number is now effectively 1 and infections will start to fall.

Omicron’s rapid spread

Despite New Zealand’s high vaccination rates, omicron is spreading quickly here, as it has in other countries. There are many elements to this.

Omicron is good at avoiding immunity generated by vaccination and previous infection. We have very high rates of first and second doses, but fewer than 60% have received boosters, and we have a very short history of exposure to natural infection.

These characteristics make us prone to a rapid and large outbreak of omicron. Further, vaccinations, including boosters, are very good at preventing illness, hospitalisation and death, but they don’t prevent infection and transmission quite as well.

This means that even in a highly vaccinated population, you can still get high levels of transmission and infection, but the rates of illness and severe complications will be much lower.

Relaxation of public health measures and the impact of superspreader events may also be contributing to the current picture. Importantly, while the number of infections has increased dramatically with omicron, the proportion of these that result in severe complications is much lower than during the earlier delta outbreak.

Our behaviour helps determine the size of the wave

The earlier cases start to fall, the smaller the overall outbreak will be. If R is 2 at the start of an outbreak, a basic model says around 80% of the population will be infected. If the initial R number can be reduced to 1.5, only 58% of the population get infected.

Luckily we exert some control over the R number. Measures like mask wearing, good use of ventilation, self-isolation when symptomatic or after a positive test, vaccination, and avoiding crowded indoor areas all work to reduce R and the total number of people who will get infected. Local modeling suggests that depending on how well we adopt these measures, somewhere between 25% and 60% of the population are likely to be infected in this outbreak.

Even when sharing the same household as a case, it is not inevitable everyone else will get infected. Studies from the UK, Denmark and South Korea have all looked at the probability of susceptible people in the same household as a positive case getting infected.

They found with omicron, this probability is somewhere between 15% and 50%. In other words, you still have a better than even chance of avoiding infection through your infectious housemate.

All the measures that work generally to reduce spread also work within a household. Mask up inside, get air flowing through, where possible move the infected household member into their own bedroom and bathroom, and practice good basic hygiene.

The relationship between the initial exposure dose, infection and disease severity is a property of many infectious diseases, including respiratory diseases in humans and other animals.

A recent review concluded that while there is good evidence of a direct relationship between the Sars-CoV-2 virus dose and infection in humans, evidence for a link between dose and severity is lacking, despite some evidence from animal models.

Covid severity is most likely driven by factors other than the initial exposure dose. These include the virus variant and host factors such as age or the presence of some pre-existing health conditions.

All the standard public and personal health measures will help us avoid getting infected and reduce transmission to the more vulnerable, thereby reducing the number of people with severe illnesses.

David Welch is a senior lecturer in computer science at the University of Auckland and Nigel French is a professor of food safety and veterinary public health at Massey University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.