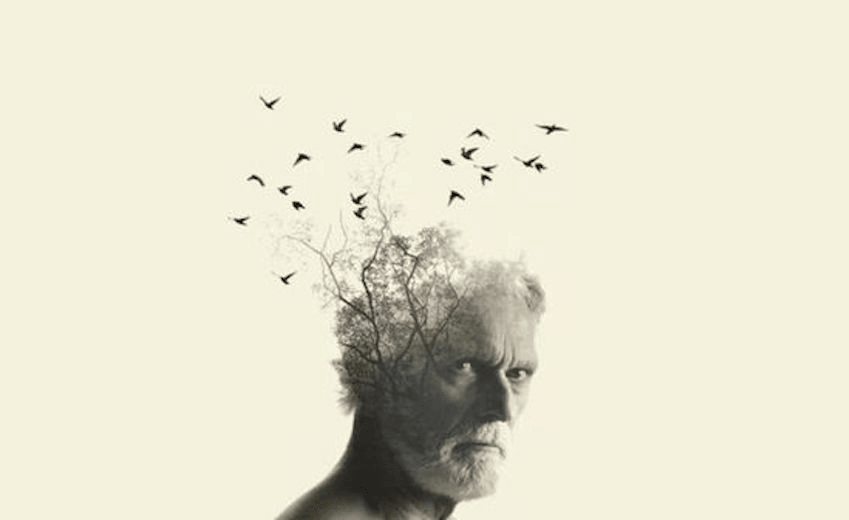

There’s a lot of confusion around the symptoms and effects of dementia. Now, neuroscientists are partnering with playwrights to give a voice to the research.

In labs and clinics across New Zealand, researchers are working towards an ambitious goal: to understand the biological mechanisms behind Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s and Parkinson’s diseases, as well as stroke and sensory loss. What links these conditions is age. Neurodegenerative disorders like these tend to be much more common in people aged 65+ than in any other age group. And the size of that older population is ever-increasing. In 1981, those aged 65+ represented less than 10% of the New Zealand population. Today it’s 15%, and the latest statistics suggest that by 2038, one in four New Zealanders will be aged over 65.

“Living longer is one thing,” says Otago neuroscientist Professor Cliff Abraham, “[but] we want ageing to be a positive experience, and through our research, to improve the quality of life for older people.” Abraham is the co-director of Brain Research New Zealand (BRNZ), a partnership between the University of Auckland and the University of Otago. BRNZ’s research is interdisciplinary, with scientists working on everything from disease biomarkers to population health. Abraham explains that, as a result, they and their collaborators at the University of Canterbury and Auckland University of Technology use a variety of tools.

“In some areas, it might be cultured human brain cells or different animal models. We have developed new technologies and trialed therapies. We also work on large-scale longitudinal studies, which are helping us to identify the risk factors, lifestyle factors and social factors that contribute to brain decline.”

One of BRNZ’s focus areas is dementia, of which Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form. Different from ‘normal’ age-related memory loss, dementia is a progressive condition that alters the structure and function of a person’s brain. Its symptoms vary between individuals, but even in its early stages, dementia can significantly limit a person’s ability to perform everyday tasks. And the impact of the disease is felt not only by those living with it but also their whānau.

It’s this wider impact of poor brain health that, Abraham says, motivates him to look beyond the lab. “As scientists, we naturally turn to peer-reviewed articles and public lectures to share what we do, but it’s important to find other ways to connect with our community.” Through the national network of Dementia Prevention Research Clinics, Abraham and his team work directly with people experiencing memory problems, as well as collaborating closely with charity groups and schools. This year, BRNZ are trying something a little different – they’re sponsoring a national tour of the ground-breaking play The Keys Are in The Margarine.

Created by a Dunedin-based theatre company, The Keys uses a performance technique known as verbatim, or word-for-word, to showcase the realities of living with dementia. Co-creator Cindy Diver says that this approach is a way to “tell truthful stories in a truthful manner.” She first started exploring verbatim theatre 11 years ago as part of a research group at the University of Otago. Initially, Diver says, they explored the “quirkiness of humans, and their fears and comforts”, but she quickly realised how valuable this form of theatre could be in vulnerable settings where there is “a stigma around a topic, which means that it isn’t necessarily safe for a person to share that story.”

The first topic that Diver tackled was a difficult one: family violence. Working with Professor Stuart Young and Associate Professor Hilary Halba from Otago’s School of Performing Arts, Diver met with survivors and perpetrators of family violence, as well as medical professionals and members of the police force. Their research bettered their understanding of a crucial, complex topic, and was central to creating the play.

In verbatim theatre, productions aren’t strictly ‘written’. Rather, each play is assembled from real-life conversations. The first step is to record interviews with a wide variety of people, known as collaborators. These interviews are edited into a documentary that is shared only with the actors. Then, as Diver explains, each actor uses the film to learn their parts by “studying the collaborator’s eye movements, hesitations, hand gestures, vocal intonations, and every word of the edited interview.” While they perform on stage, each actor also listens live to the audio of their collaborator, via an earpiece. “The actor speaks in time with that person, which means they stay 100% honest,” says Diver. “This process allows us to bring the audience into the collaborator’s room, while keeping that collaborator safe and completely anonymous.”

The result of the Otago research project was the team’s first verbatim play, Hush, which debuted to wide acclaim in 2010. The idea for creating a similar play on dementia came later, through a connection with Dunedin GP Dr Susie Lawless. Among her patients, Lawless had noticed that Alzheimer’s and other dementias were shrouded in stigma, and that people were confused about their symptoms and the disease’s progression. Having been a collaborator on Hush, Lawless felt that a verbatim play might help untangle some of that complexity. Together, Lawless and Diver collaborated again with Young and began developing The Keys Are in The Margarine.

The play finally hit the national stage in 2015 and immediately caught the attention of former BRNZ director, Professor Richard Faull. Diver knew that Faull and the wider BRNZ team would be fantastic collaborators. “They really seemed to appreciate that research could be made more palatable through art.” Shortly after that first tour, Diver was invited to speak to BRNZ’s early career researchers, and alongside her Lawless, later presented at an International Alzheimer’s Conference in Australia. “The doctors and researchers understood that what we were doing didn’t fit on a clinical diagram,” she says, “but it had immense value at a personal level.”

Abraham agrees, saying that although dementia is a difficult thing to discuss, “we shouldn’t shy away from its emotional impact. The Keys is a fantastic, entertaining piece of theatre, but it also makes people think – about what it means to be diagnosed with the disease, or to live with and care for someone who has it. The verbatim format gives it nowhere to hide – the physical, emotional and social costs of Alzheimer’s are there for all to see.”

This is not the only time neuroscience and the arts have overlapped. Long before biomedical imaging technologies, physician Ramón y Cajal’s remarkable drawings helped him to prove that neurons are individual cells. It was a discovery that saw him share the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. The two fields have previously collided on stage, too. Canadian rapper Baba Brinkman and his wife, neuroscientist Dr Heather Berlin, regularly combine their talents to create brain-related shows, and US playwright Edward Einhorn has been working in what he’s dubbed ‘neuro-theatre’ for more than a decade. In the UK, Professor Sarah-Jayne Blakemore recently worked alongside teenage performers to create Brainstorm, a play that explores adolescent brain development. And earlier this year, neuroscientists tried to understand the neural basis of dramatic acting by placing actors into an MRI machine while they adopted characters from Shakespearean plays.

From the actor’s point of view, collaborating on such an emotional topic is a unique experience. “Alzheimer’s is a disease that is full of uncertainty, and we’re understanding more about it all the time,” says Diver. “But the emotions of coping with it – as a patient or for the people around them – they all come down to what it means to be human. Combining art and science to unpick all of that is very, very powerful.”

For the full list of dates, venues and details of where to buy tickets to The Keys Are in The Margarine, click here.

A panel on the science of dementia follows the Wellington performance this Saturday, with Cindy Diver, Prof Cliff Abraham, Dr Phil Wood (Ministry of Health chief advisor on healthy ageing) and Prof Lynette Tippett (Director of NZ’s Dementia Prevention Research Clinics).

Laurie Winkless contributes to the BRNZ website