Auckland University researchers say beams of timber stuck onto the backs of unreinforced masonry façades could be a cheap and simple way to stop them collapsing in an earthquake. Laura McQuillan investigates.

Owners of nearly 140 buildings from Lower Hutt to Canterbury have been given until the end of March to secure unreinforced masonry façades and parapets that pose an “immediate danger” to passers-by. After that deadline, building owners who haven’t done the work face non-compliance fines of up to $200,000.

But councils are saying that work to secure masonry is only underway on about a quarter of the buildings, and just one (in Wellington) has so far completed it.

With the clock ticking, Auckland University seismic engineering lecturer Dr Dmytro Dizhur is encouraging owners and engineers to consider wood to quake-safe their buildings.

How would wood work?

The idea for using wood to secure façades arose out of the Christchurch quake, where timber frames stayed standing while the masonry in front of them collapsed.

Dizhur thought: why not fasten the two together?

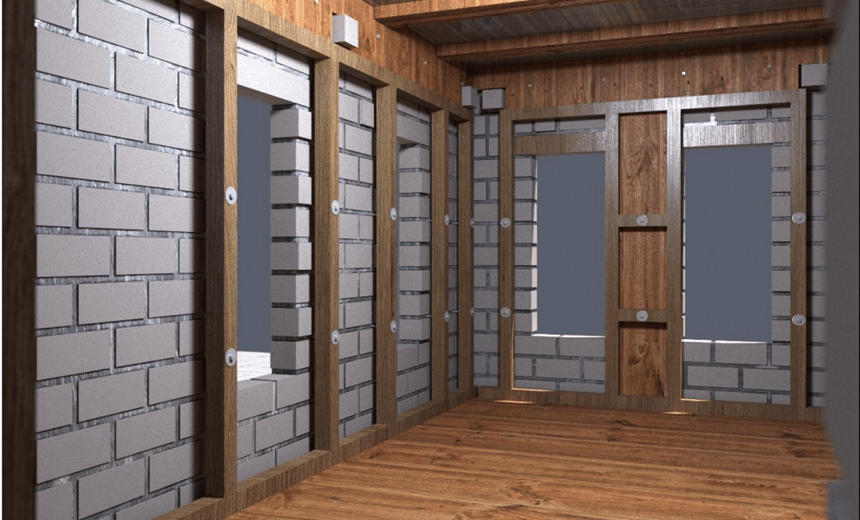

His solution is almost as simple as popping down to Bunnings for a load of timber strongbacks, then fastening them vertically along a brick wall at certain intervals, and to horizontal beams connected to the floor and ceiling.

“Masonry has very little tensile strength, so it’s just sort of a stack of bricks on top of each other, and as soon as you push them sideways, they tend to just [fall] as a stack of bricks,” he says.

“What the timber does, in the regular spacing, is just holds everything together, so you actually engage the weight… You’re actually using the heavy aspect to your advantage.”

Both the wood’s thickness, and the size of the space between beams, need to be carefully calculated, and Dizhur presented those calculations to the Structural Engineers’ Society conference on November 2. His team is currently in the process of manufacturing special screws to anchor the timber to masonry, with nothing on the market quite right for the job.

In Dizhur’s tests, the timber and masonry combo “seems to have performed extremely well”, withstanding three times as much ground acceleration as a wall without it.

“We took it up to as high as 1.3g, which, in a New Zealand context, is quite high,” Dizhur says.

That’s the same ground force acceleration measured at Ward in North Canterbury during the Kaikoura quake, though 3g was measured in Waiau during the same quake and 2.2g during the Christchurch quake.

Dizhur says there’s no reason why the wood technique wouldn’t work on a two or three-storey building on Wellington’s Cuba Street, though some buildings – including those with parapets – will need additional retrofitting methods.

“There will be cases where it’s going to be a sole solution, but in other cases, it will be part of a package. It’s not a magic bullet, but it addresses one of the biggest concerns and one of the most expensive concerns.”

As for why no one’s thought of using wood before, Dizhur points out they did – 3000 years ago.

“Ancient Greeks and ancient Romans already had ideas of combining timber and masonry, in a slightly different fashion, but the basic principles are the same. We’re not actually technically inventing anything new, we’re just rediscovering the old knowledge.

“People get on a tangent with over-complication and sophistication with all the technology that allows you to do that, but if you just step back and look at the principles, usually the answer is right in front of your nose.”

Canada’s magic concrete

While the Auckland team was screwing wood onto masonry, researchers at the University of British Columbia in Canada were mixing fibre with cement and spraying it onto concrete walls.

The new material, called eco-friendly ductile cementitious composite (EDCC) and nicknamed “quake-resistant concrete”, can make a wall “bend” enough to withstand nearly twice the force of the magnitude-9.1 quake that hit Japan in 2011.

It’s not the first fibre-reinforced concrete in existence: a similar New Zealand product, Flexus, was launched about seven years ago but discontinued in 2015.

But at just $10 (NZD $11.20) per square metre, EDCC is touted as the cheapest on the market – ideal for use in quake-prone developing countries.

Releasing an impressive video of an EDCC-coated wall surviving an earthquake simulation, UBC said it “could save the lives of not only British Columbians but citizens throughout the world”. Canada’s so amped about the innovation that it’s already been added to British Columbia’s seismic retrofit program and will soon be used to upgrade schools in both Vancouver and India.

Researcher Salman Soleimani-Dashtaki said it’s also perfect for Wellington’s heritage buildings, saying it can be applied to just the rear of a wall, without altering the front.

And he’s “very confident” that, had the material been used in Christchurch prior to 2011, it could have prevented deaths from falling masonry.

“Maybe the buildings still needed the restoration after the earthquake, but the number of bricks, clay bricks, and debris that was flown away could have been prevented, could have been avoided by a factor of 10, I would say.”

If further testing outside the lab proves it’s as good as the researchers believe, they hope to have it on the market next year.

The idea of using EDCC in Wellington was run past property mogul Ian Cassels, who said he’s “mad keen” to try it on his buildings, which include Island Bay’s red-stickered and empty Erskine College, and others on Cuba Street.

“$10 a metre is a very, very low price for any type of coating, particularly if it’s engineered-type coating, it’s gotta have reasonable thickness and volume to it,” the director of the Wellington Company says.

“I think it’s a fabulous idea but I just can’t believe it’ll work.”

Neither can a Kiwi expert who attended a technical presentation by the Canadian researchers in Los Angeles.

“On the [UBC] video, it appears that people are getting earthquake-resistant concrete. There’s nothing as such,” says University of Canterbury engineering professor Stefano Pampanin.

“It’s not one single technology or technique which is going to save the building from being earthquake-prone or not… It’s just that this can become part of a toolkit of an engineer.”

Pampanin was quick to add there were positives to the Canadians’ research – but it wasn’t the silver bullet it had been made out to be.

“New materials are being developed further and further. They are reaching a point where they’re becoming cheaper – that’s absolutely fundamental – and they’re becoming more and more feasible to be applicable.

“The more we go, the more people will be able to use simple and cheaper, but very performant, materials and technology. That’s the good news. But yes, it has been oversold.”

Would either fly in New Zealand?

Neither the Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) nor Wellington City Council wanted to endorse an innovation, saying it’s up to owners to decide the right way to improve their building’s performance.

If EDCC were to be used in New Zealand, its manufacturers would first have to prove it meets Building Code standards – so if it makes it to hardware store shelves, it’ll be long past the March deadline.

But while most owners of Wellington’s 96 must-fix buildings will use steel beams or strapping to secure their façades, wood could be used on some, the city’s chief resilience officer Mike Mendonca says.

“There’s a guy who owns a garage in one of the suburbs, and his is a pretty simple job where he just needs to remove the parapet, weather-tighten what he’s done, and just get on with it… I wouldn’t say it’s quite as simple as go to Bunnings and get a bit of 4×2, but it’s not too much more than that,” Mendonca says.

“There are a bunch of those, but we’re being very careful not to generalise because you simply can’t do that on the building that’s on the main corner outside the hospital, for example.”

He’s referring to the iconic Ashleigh Court Private Hotel, at the corner of Riddiford and Rintoul streets, a heritage building that “needs architectural services, professional builders, traffic management, that kind of thing”.

But, adds Mendonca, “horses for courses – in some cases, yep, Auckland University’s actually right.”

So mark that down as a win for the wood team – though the real champs are those building owners who are putting in the effort and expense to secure their masonry, whichever way they choose to do it.

The Spinoff’s science content is made possible thanks to the support of The MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology, a national institute devoted to scientific research.