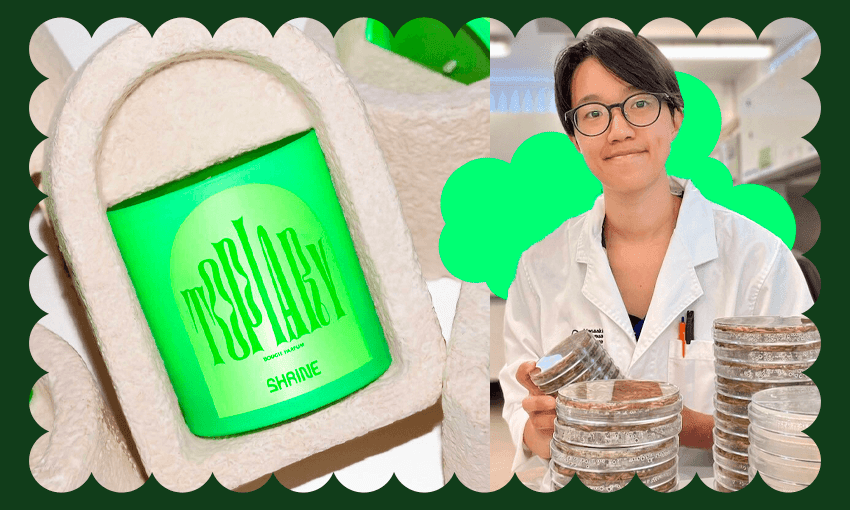

Biotechnologist Jess Chiang is using native fungi to create alternatives to plastic packaging. And she’s eager to discover how else they can improve our lives.

What do boogie boards, disposable coffee cups and packing peanuts have in common? Well, none of them is doing the planet any favours. For nearly a century, expanded polystyrene (EPS) has been a mainstay in the construction, packaging and food industries. Yet the rigid foam, petroleum-derived material takes an estimated 500 years to decompose, releasing suspected carcinogenic and neurotoxic chemicals in landfills. Its buoyancy and lightness make it prone to being blown away, polluting waterways and eventually oceans, threatening marine wildlife. Even its manufacturing process contributes to the depletion of the ozone.

Commonly known as Styrofoam, EPS is one of several plastics that people are trying to find eco-friendly or biodegradable alternatives to – think reusable coffee cups, glass food containers, compostable rubbish bags and even the simple brown paper bags you find at supermarkets. Contributing to this work is 26-year-old international student Jess Chiang, the chief scientific officer (CSO) at biotechnology startup BioFab, based in Auckland.

BioFab is working toward commercialising what it calls “mushroom packaging”, a biocomposite made of mycelia and hemp hurds, a byproduct of the fibre hemp industry. The agricultural waste is upcycled into food for mycelia, the vegetative part of fungi capable of building macrostructures, such as BioFab’s particular packaging moulds. Mycelia’s cell walls are made of chitin, a molecule that gives the exoskeletons of crabs and insects their durability and toughness. “We don’t necessarily tell it what to do, but we’ll give it a space to grow into and then it’ll fill up the space completely,” Chiang explains.

The end result is a solid material that supposedly biodegrades within a month, resists fire and repels water. In other words, it performs just as well as polystyrene without harming the environment.

You’d normally encounter mycelia via their fruiting bodies – mushrooms – on the forest floor or stacked on produce shelves. But entangled and entwined through layers of soil and organic material are mycelia’s delicate filaments, a life force connected to the roots of plants and trees to form a symbiotic “wood wide web”. Information and nutrients are communicated via this network – dying trees might redistribute their remaining resources to those in need or young saplings might be bolstered by their stronger neighbours to grow. It’s even understood that plants, when threatened by browsing animals, damaging bugs or invisible diseases, can warn others nearby to raise their defences.

Fungi are being touted as the green material of the future, potentially capable of cleaning up oil spills or even helping defend against infectious diseases. So what’s the catch? Chiang explains that BioFab’s technology, licensed from American sustainable materials company Ecovative, is nascent and as yet untried and untested at scale. And because the startup is using a local strain of fungi, understanding the optimal growing conditions to then expand production will require more work.

At the moment BioFab is trying to convince investors of its potential, with the goal of constructing a pilot plant, although Chiang admits the task is proving harder than expected. There are some promising signs though – in the next five years, around the world, an estimated $203 trillion will flood into capital projects geared at decarbonising economies and renewing critical infrastructure. And the New Zealand government’s first stage of phasing out hard-to-recycle and single-use plastics is imminent, with polystyrene and EPS takeaway food and drinks packaging set to go by October. In Australia, seven out of eight states and territories have already committed to banning single-use plastics. “It’s perfect timing,” Chiang says.

As a kid, Chiang dreamed of being a wildlife expert and conservationist, inspired by watching the late Steve Irwin’s Crocodile Hunter TV series. Originally from Taiwan, she moved to Aotearoa in her high school years before going on to study biotechnology at university, a subject exploring technologies based on harnessing the power of living organisms. Biotechnology is a different kind of conservation, a way “to even out the firmware, the hardware, the robotic stuff that’s in our everyday life,” Chiang says. “Everything is hard and cold – what if we created biotechnology that could provide some nature in your home?”

In 2017, while attending youth-led non-profit Global Biotech Revolution’s GapSummit conference, Chiang and three other biotech students pitched a solution rooted in sustainability as part of a competition. “Team Kosmopolites” reimagined Styrofoam packaging made of 3D-printed fungal material – an idea that had earlier won Chiang the best bioscience business idea award at Auckland University’s Velocity Innovation Challenge. She won again. A few years later, she came across BioFab’s work online, reached out to its founders and, since the end of 2020, has been leading the company’s research and development function – work that she can count toward her PhD.

As part of her research, Chiang wants to look at how New Zealand’s indigenous fungi can serve as biomaterials. Given the country’s geographic isolation and endemic biodiversity, the scientist believes its native spore-producing organisms are unique. She’s already started studying the national collection of Crown research institute Manaaki Whenua, which estimates about 7,300 species of fungi have been reported in Aotearoa and that twice that number await discovery. Chiang’s next step is connecting with hapū and iwi to learn about their traditional knowledge of fungi.

She’s eager to engage with mātauranga Māori as part of her post-graduate research, so establishing partnerships feels right. But consulting with Māori will be critical; the chief scientist wants reciprocal, enduring relationships and simply presenting iwi with BioFab’s terms and conditions won’t cut it, she says. Discussions are yet to happen, simply because Chiang is still in research mode. But in understanding how indigenous fungi are connected to the land and tangata whenua, and how that connection can be honoured, New Zealand could be a world leader in indigenous mycelia biotechnology. “There’s not a lot of other companies around the world that have been trying to make this happen,” she says.

That’s what she admires about fungi’s potential – it’s still a mystery. People have discovered numerous uses for plants and trees, from food to pharmaceuticals, timber exports and construction. With fungi, an altogether separate kingdom, humans have known only about their culinary and medicinal qualities. But that’s changing – building products like acoustic panels and floor tiles are being manufactured from fungi and even fashion is heralding the arrival of mushroom leather hats. “If we can make [plants] into all sorts of materials,” Chiang asks, “why can’t we do that with fungi as well?”