The conversation around how we prepare for coronavirus here needs to be guided by a sense of our common humanity, write Ruth Cunningham, Charlotte Paul, Andrew Moore, Ayesha Verrall of the University of Otago.

Borders have been closed, arrivals from Wuhan are in quarantine, and New Zealanders who have travelled from China are being asked to “self-isolate’’. Despite 49,000 lab-confirmed cases of Covid-19 worldwide, there are, as yet, no cases in New Zealand. They are, however, expected.

These public health measures need to be justified in terms of both the rapidly changing scientific data and the application of ethical values; otherwise, fear of an outbreak can lead to excessive coercion and race-based stigma. In these situations, efforts to prevent the outbreak can cause more harm than good. Our decisions need to be guided by a sense of our common humanity; a sense that “it could be me”. As Dr Tedros Adhanom, director general of WHO, said earlier in the month: “We are all in this together, and we can only stop it together.” Our shared responsibilities to each other need to become part of the conversation and preparation for Covid-19 here in New Zealand.

The National Ethics Advisory Committee developed and widely consulted on ethical values for managing each phase of a pandemic, as part of New Zealand’s pandemic preparedness efforts. Getting Through Together explores the place of widely shared ethical values. The committee arrived at two sets of values for decision-making: those informing how we make decisions and those informing what decisions we make.

Good decision-making includes following good processes such as being open to public scrutiny and being explicit about the science and values that underlie decisions. This builds trust and confidence in authorities, and leads to greater acceptance of public health measures. After all, the reality of New Zealand’s small public health workforce means in a pandemic we are reliant on voluntary adherence to measures such as self-isolation. For public health measures to succeed, people and communities need to trust decision-makers.

The values and processes outlined in Getting Through Together offer support to decision-makers at all levels of society who face difficult choices. At this stage, where the focus is on border control, decisions are being made about who is allowed into New Zealand. The World Health Organisation has cautioned against border control actions that promote stigma or discrimination. Closing borders has the potential benefit of delaying the arrival of people infected with Covid-19. But as the epidemic develops and more is known about both the infectivity and the case fatality, the benefits of border closures may be outweighed by potential harms.

When restrictive measures are required, the least restrictive measures possible should be used. People subjected to restrictive measures such as quarantine may be deprived of their freedom of movement, but they should not be deprived of other rights. Quarantine measures can be implemented in ways that are respectful, supportive and fair, and cater for diverse needs.

Similarly, reciprocity is crucial when people are subject to quarantine because quarantine is performed for the good of others, not for the person’s good. In other words, people are required to bear an extra burden in the interests of others. Reciprocity can be expressed by ensuring people who are quarantined are given extra support and well looked after, in keeping with the extra burden they carry for protecting others.

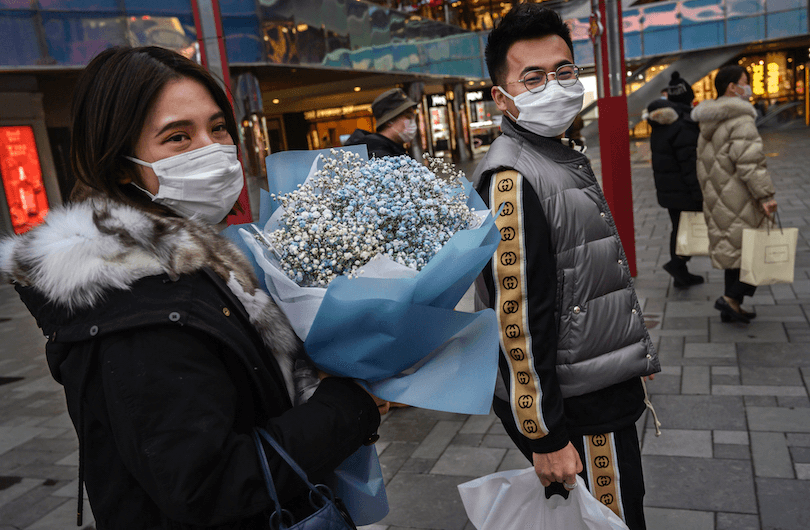

In New Zealand, Chinese people have already experienced stigma and discrimination associated with fear of the coronavirus. It is encouraging that at the Whangaparāoa Reception Centre, where 157 people from Wuhan are being held in quarantine for two weeks, the Ministry of Health organised Chinese New Year celebrations. Director general of health Dr Ashley Bloomfield said, “Chinese New Year is an important cultural event and we organised this to honour that for both our guests with Chinese heritage and all others.”

This is exactly the respect and reciprocity we need.

With the potential that an increasing number of people will require quarantine or isolation if cases occur here, the responsibility for providing this support will not remain with government agencies alone. We will need to recognise the values of neighbourliness and unity in coming together to support those whom we are asking to “self-isolate”. This might mean offering to walk a neighbour’s dog, or drop around a casserole. It’s worth thinking now about neighbours who might need extra support.

These values will also inform prioritisation decisions by health professionals who care for those who become ill, and guide consideration of what we owe to these professionals who care for the sick. Recognising the humanity of healthcare workers means prioritising their special need for protection with evidence-based equipment. It also means ensuring healthcare workers are not unduly penalised in terms of lost wages or sick leave if they are stood down from duties (for up to two weeks) following unprotected exposure to the virus. Otherwise non-disclosure of exposures could lead to infectious healthcare workers transmitting the illness in hospital. These types of issues are most pressing for staff like cleaners who play a vital role in hospital decontamination and yet are often low paid and on casual contracts. Finally, healthcare workers are among New Zealand’s most multicultural workforce and racism during a pandemic undermines the cohesion of a workplace under extraordinary pressure.

New Zealand needs to prepare for managing Covid-19 cases. This includes improving hand and respiratory hygiene practices, making available personal protective equipment, and preparing for potential self-isolation, as well as preparing our health system to cope with increased demands. It must also include much more, through discussions at all levels of society about our shared responsibilities to each other.

We use ethical values all the time in deciding how to behave; what is different with a pandemic is that there will be many conflicts between our impulses to protect ourselves and our families and the protection of our common humanity.