How the process runs, why we’re not testing everyone who feels ill, and something you can do online immediately and easily to help the fight against the virus.

The Spinoff’s coverage of Covid-19 is funded by Spinoff Members. To support this work, join Spinoff Members here.

With confirmed cases of Covid-19 in New Zealand up to 12, many influential people are writing open letters and opinion pieces and doing press conferences asking why we aren’t pulling out all the stops and testing thousands of people a day like they are in South Korea. The thing is, testing for Covid-19 isn’t like a pregnancy test. You don’t just pee on a stick, wait a few minutes and get a result. Allow me to explain.

Step 1: Take a sample

To test for Covid-19 you first need the right samples, and these will differ depending on the person and the symptoms they present with. So, the first important thing is whether the right sample is taken by a competent person. To scale up our testing we would have to put resources in to making sure we had enough people trained up to take the swabs. We can do this, but it will take resources away from somewhere else.

For most people, a simple swab can be taken from the mouth and throat, or the back of the nose (check out the video here). For others, we might use sputum, which is the gunk coughed up from the lungs by some patients. For some, the sample might be from a procedure called a bronchoalveolar lavage. To get this sample, someone puts a tube down your mouth or nose into your lungs, squirts some fluid into your lungs, and then collects the fluid back again. Some people have had negative throat and nose swabs but positive bronchoalveolar lavages.

Oh, and guess what. The long cotton-bud thing they use to take the swabs comes from overseas. Again, sourcing them at some point may become an issue.

Step 2: Send samples to the lab

Here in New Zealand we have several labs around the country all set up to test for the Covid-19 coronavirus. The director general of health, Ashley Bloomfield, has said that our current capacity is to do 770 tests each day and that should rise to 1,500 per day later this week. And remember these labs are also currently doing diagnostic tests for other diseases that aren’t likely to just disappear.

Again, to get greater capacity, people will be being trained up to process and test the samples. If we needed to do more, we could use the labs and scientists in our country’s universities and Crown Research Institutes. They would need proper training though to make sure they were carrying the tests out to the appropriate standard.

Step 3: Extracting the virus

To understand the next step of the test, it helps to know a little more about the virus responsible. Think of it like a bar of chocolate – a filling encased in a layer of chocolate, served up in a wrapper. The filling is the virus’s genetic material, the chocolate its proteins, and the wrapping a layer of lipids. The Covid-19 coronavirus’ genetic material is RNA.

Once you have a sample, next you have to extract the virus’s RNA from all the other stuff – the human cells, the bacterial cells, and any other junk. This is done in a special type of lab using a commercial kit and there are reports overseas that these are becoming limited. In New Zealand we import these kits from the US and Germany. I’ve heard from scientists in the US that some hospitals are calling local university labs and asking if they have any kits stashed away because they are having trouble getting enough.

Around the world, scientists are trying to develop ways to bypass this step so the test can be run straight from the patient samples. Here in New Zealand, in Gisborne, John Mackay from dnature diagnostics & research Ltd is one of them.

Step 4: Detecting the Covid-19 coronavirus

After extraction then it’s time to see whether the Covid-19 coronavirus is present in the sample. The test is what is known as a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) and is based on detecting unique sequences in the virus’s RNA by a method called reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR). Because the Chinese released the genetic sequence of the virus so quickly, that allowed tests to be developed and the methods released to the world so any country could do the test if it needed to. This is where the US screwed up. They decided to develop their own test instead. And then that ended up not working properly, which lost them valuable time.

This part of the test also uses special reagents and again these are commercially available and imported from overseas. The kit, and a piece of equipment that switches temperatures really fast, turns any RNA present into DNA and then if any of that RNA belonged to the Covid-19 coronavirus it makes loads and loads of copies of it which can be detected. This is what gives a positive test. If none of the RNA belonged to the virus then there shouldn’t be a detectable signal.

The limiting factors at this stage are the availability of the reagents and the amount of virus present in the sample. Too little virus and the test won’t be able to pick it up. This is another thing Mackay and other scientists have been working on and the test now in use is much more sensitive than it was a couple of months ago.

While we have substantial stocks of the reagents, we don’t have enough to test everyone in the country. It’s also the same reagents needed to test for other viruses like influenza. As we are heading into flu season, we will need to make sure we have enough reagents to be able to do those tests too.

Read more from Siouxsie Wiles here.

Test. Test. Test?

So, to recap. We have a finite number of kits to run the tests and the same kits are needed to test for flu. As other countries ramp up their testing needs these kits are becoming more difficult to get hold of. In other words, it would be bad to use them all up before we actually need them.

When the outbreak first started, tests were only run on people with specific symptoms and who had travelled overseas. Those conditions have now been relaxed, and doctors have been encouraged to use their discretion, but it is still only symptomatic people who are being tested. At this stage it doesn’t make sense to do the kind of testing South Korea is doing. It will waste a valuable resource. South Korea ramped up their testing when they had multiple cases of people in the community transmitting the virus and it was important to find all those people. We could do the same if we needed to.

What about reports of ‘hidden’ cases?

A study just published has reported that in the early stages of the Covid-19 outbreak in China, as many as five to 10 people infectious people were shedding the virus for every one case that was diagnosed. One thing to remember about this study is that it is based on a limited number of cases from early in the outbreak.

Analysis of over 50,000 cases led the WHO and Chinese health officials to conclude that around one out of every six people who gets Covid-19 becomes seriously ill and develops difficulty breathing. The expanded testing criteria haven’t yet picked up any sign of this in people who are hospitalised with respiratory problems and have no overseas travel. I’m pretty sure all our medical staff are now on the alert for the virus.

What you can do to help

While the Ministry of Health look at other strategies for early detection of Covid-19, there is one we can all help with right now. We need every household in New Zealand to sign up to the FluTracking project. Each week you’ll be sent an email asking if anyone in your house has had a fever or cough. This information is being used as an early warning system for Covid-19.

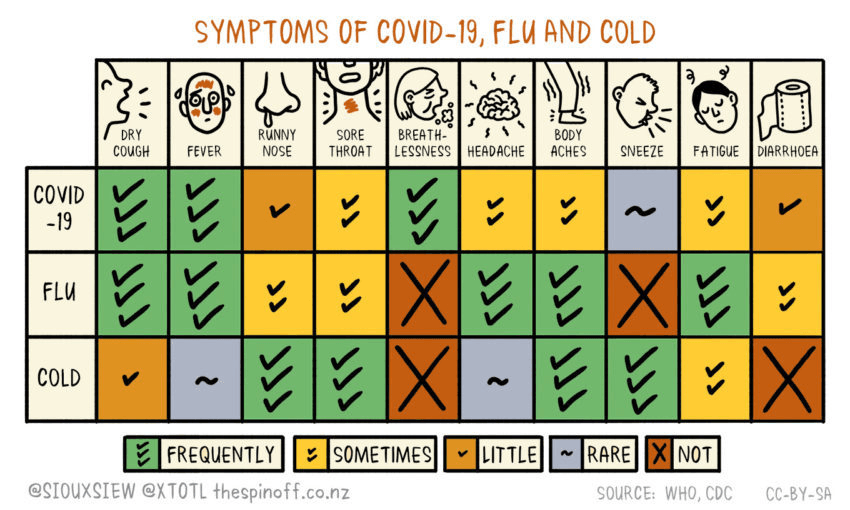

So, in summary. If all you know about testing for infectious diseases is stuff you’ve been reading on the internet, then stop tweeting your reckons and firing off your hot takes. Sign up to FluTracking. Wash your hands. Stay at home if you start to develop any symptoms. If you’re unsure what those symptoms are, we’ve got you covered. Check out Spinoff cartoonist Toby Morris’s handy guide (click here for a printable, high-res PDF version).