A new strain of ryegrass developed in NZ promises to reduce water demands and curb emissions. But it’s genetically modified, and no matter how settled the science, the politics may be unpalatable, writes Bob Edlin of the Point of Order blog, where this post first appeared.

Environmentalists should be encouraging New Zealand’s development of ryegrass with its potential to substantially increase farm production, reduce water demand and decrease methane emissions.

It is understood that the grass has been shown in AgResearch’s Palmerston North laboratories to grow up to 50% faster than conventional ryegrass, to be able to store more energy for better animal growth, to be more resistant to drought, and to produce up to 23 per cent less methane (the largest single contributor to New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions) from livestock

On top of these environmental benefits, the potential value of GDP based on AgResearch’s modelling “is in the range of $2 billion to $5 billion in additional revenue depending on the adoption rate by farmers,” AgResearch principal scientist Greg Bryan said almost two years ago.

There’s just one snag.

It’s a genetically modified ryegrass.

Under New Zealand’s strict rules, no one can plant a GM seed in an open paddock and our scientists can’t test new seeds developed using offshore GM technology.

The absurdity is that Sir Peter Gluckman, before stepping down as the prime minister’s chief science adviser, said the science around GM “is as settled as it will be”.

“That is, it’s safe, that there are no significant ecological or health concerns associated with the use of advanced genetic technologies,” he said.

Sir Peter accepted the political realities that this did not mean New Zealand society would automatically accept the technologies. He did hope there would be “a conversation which we’ve not had in a long time, and it needs to be, I think, more constructive and less polarised than in the past”.

Sir Peter listed some of the areas where genetic modification could be used.

They included biosecurity, the aim of making NZ predator-free and the need to change our farming systems because of the environmental impact of the greenhouse gas emissions, the water quality issues – and so on.

“We are, fundamentally, a biologically-based economy. Now, the science is pretty secure, and science can never be absolute … But the uncertainty here is minimal to nil, very, very low. I think it’s a conversation we need to have.”

Environment Minister David Parker has wearily recognised GM technologies could be used for pest control but ventured this was “many years away.”.

Labour’s confidence and supply partner, the Green Party, is more implacable in ignoring the science – even for pest control.

Conservation Minister Eugenie Sage, a Green MP, has forbidden the use of genetic modification or gene-editing as part of the goal to wipe out predators by 2050.

Sir Peter’s counterpart in the European Commission, chief scientific adviser Anne Glover, has agreed GMOs are no riskier than their conventionally farmed equivalents.

“There is no substantiated case of any adverse impact on human health, animal health or environmental health, so that’s pretty robust evidence, and I would be confident in saying that there is no more risk in eating GMO food than eating conventionally farmed food,” Glover told EURACTIV, saying the precautionary principle no longer applies as a result.

Glover said she was not promoting GMOs but declared that “eating food is risky”, then explained: “Most of us forget that most plants are toxic, and it’s only because we cook them, or the quantity that we eat them in, that makes them suitable.”

But she said scientific evidence needed to play a stronger role in policy-making and GMOs and other scientific advances must be explored to head off the increasing scarcity of energy and other resources and competition for land use.

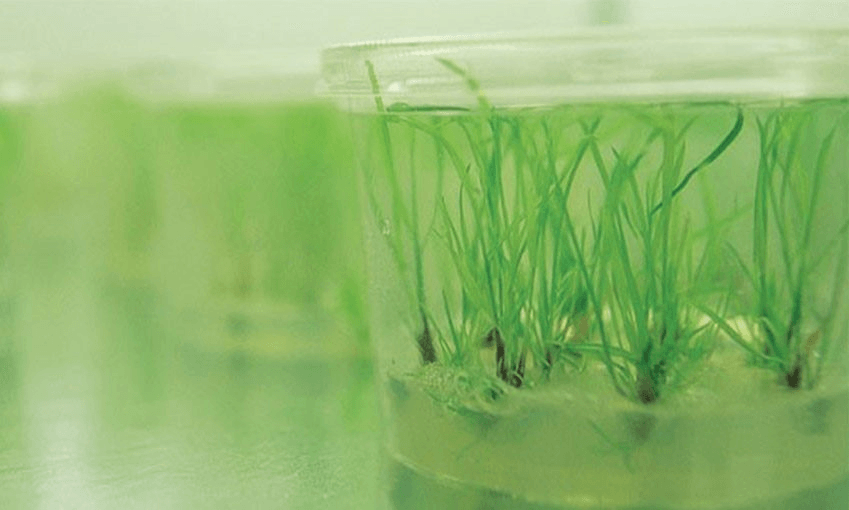

Meanwhile the genetically modified High Metabolisable Energy (HME) ryegrass developed by AgResearch is being further researched in the midwest of the United States, where genetically modified organisms can be field tested outside the lab.

Funding from the government and industry partners, including DairyNZ, is involved.

After a successful preliminary growing trial last year confirmed the conditions were suitable, Dr Bryan said the full growing trial began in the United States last month and will continue for five months.

“The preliminary trial was only two months, so it’s not over a timeframe that has any statistical merit, however we did see the increased photosynthesis that we saw with the plants in the greenhouses in New Zealand,” Dr Bryan said.

“In this full trial now under way, we will be measuring the photosynthesis, plant growth and the markers that lead to increased growth rates. While the growth has previously been studied in glasshouses in pots and as plants spaced out in the field, this will be the first opportunity to assess the growth in a pasture-like situation where plants compete with each other.

“The five-month timeframe will allow us to determine if increased growth is consistent across the summer and autumn, and we will simulate grazing by cutting plants back every 3-4 weeks. Animal feeding trials are planned to take place in two years, which we will need regulatory approvals for, and the information we get over the next two years will help us with our application for those feeding trials.”

GM opponents are unpersuaded, dismissing the US trial results as “an illusion”, but DairyNZ strategy and investment leader for new systems and competitiveness, Dr Bruce Thorrold, says the HME ryegrass is a science breakthrough and holds great potential for New Zealand farmers.

But farmers shouldn’t count on taking advantage of this great potential while our politicians are guided not by science but by their beliefs.