After Muriwai suffered a devastating landslide in 1965, it was judged too dangerous to build again on affected land. So what changed? Geologist Martin Brook tells the story.

Given the death toll, it’s important we consider the impacts of Cyclone Gabrielle sensitively. But we must also begin looking into the history of land-use and planning decisions in areas worst hit by landslides.

One such area is the beach community at Muriwai in West Auckland, where two volunteer firefighters were tragically killed in a landslide.

Several homes were cut off by slips. Residents on the steep terrain of Domain Crescent were told to evacuate on foot, rather than drive, because the land was so unstable.

Landslides can be a deadly hazard, but only when people are exposed to them. A landslide high in the Tararua mountain ranges is unlikely to pose a risk to anyone. But living near or within a landslide zone poses a clear risk.

This can be summarised as: risk = hazard x exposure x vulnerability.

Muriwai offers a case study of that equation. We already have a good understanding of the soils, landscape, geomorphology and exposure to landslide hazards – as well as the history of planning decisions that allowed houses to be built on land prone to slips.

An unstable history

Much of Muriwai, like other parts of Auckland’s west coast, is underlain by Kaihu Group sands. These are geologically young (Pleistocene age, less than 2.6 million years old) and form the high country around Muriwai.

The sands are weak and are poorly cemented, or completely uncemented, meaning there are “pore” spaces between the grains that are filled with air. During rainfall, water starts to fill these pore spaces.

Initially, this has a suction effect (negative pore pressure), whereby the water pulls the sand grains together, increasing strength. As water content increases, however, this negative pressure drops, and the sands fail and flow.

A good analogy is sand on a beach. If a little water is added, a steep-sided sand castle can be built. But if too much water is added, the castle collapses rapidly as a “flow-slide”.

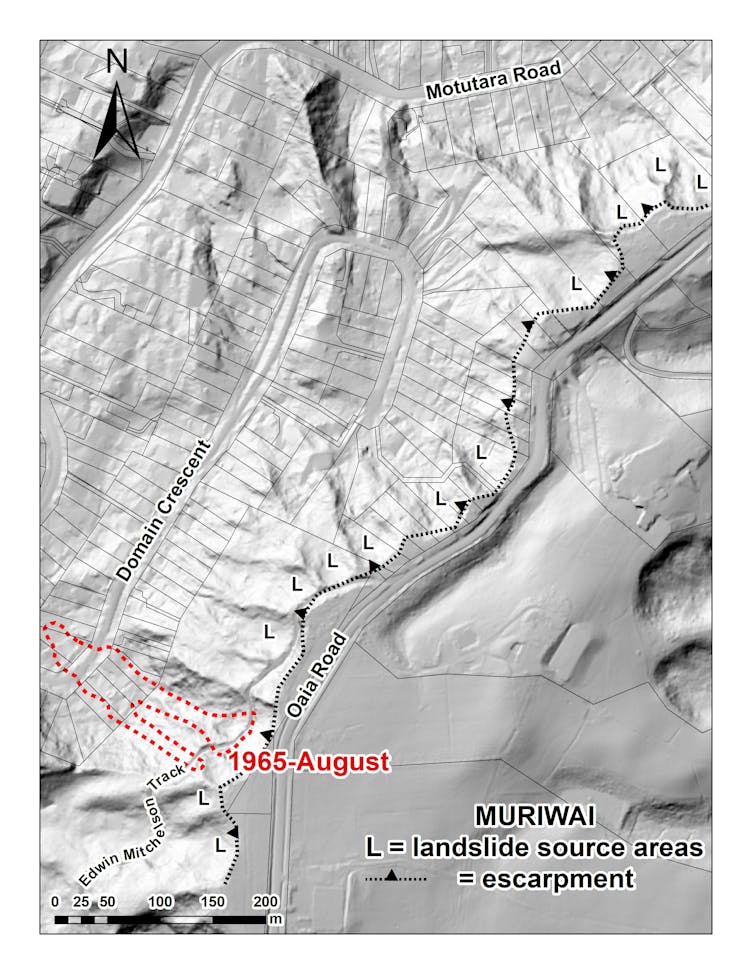

A prominent geomorphological feature of Muriwai is an escarpment of soft Pleistocene Kaihu Group dune sands that forms the crenulated ridgeline immediately west of Oaia Road. These crenulations, or “embayments”, represent the headscarps (or source areas) of landslides.

The figure below is a digital elevation model (DEM) based on 2016 data gathered by the remote-sensing method LiDAR. This uses airborne laser scanning of the land surface, which removes vegetation and exposes the land surface “geomorphology” underneath.

Landslides are denoted as “L”. Houses on Domain Crescent and Motutara Road are at the foot of the escarpment, below landslide source areas. They are constructed on Kaihu sands, with some of the houses built on debris from former landslides.

Landslides and the law

In August 1965, following heavy rainfall, fatal landslides over 200 metres long occurred on consecutive days at the south-east end of Domain Crescent, destroying houses and killing two people. The landslide extent is denoted in red hash in the figure above.

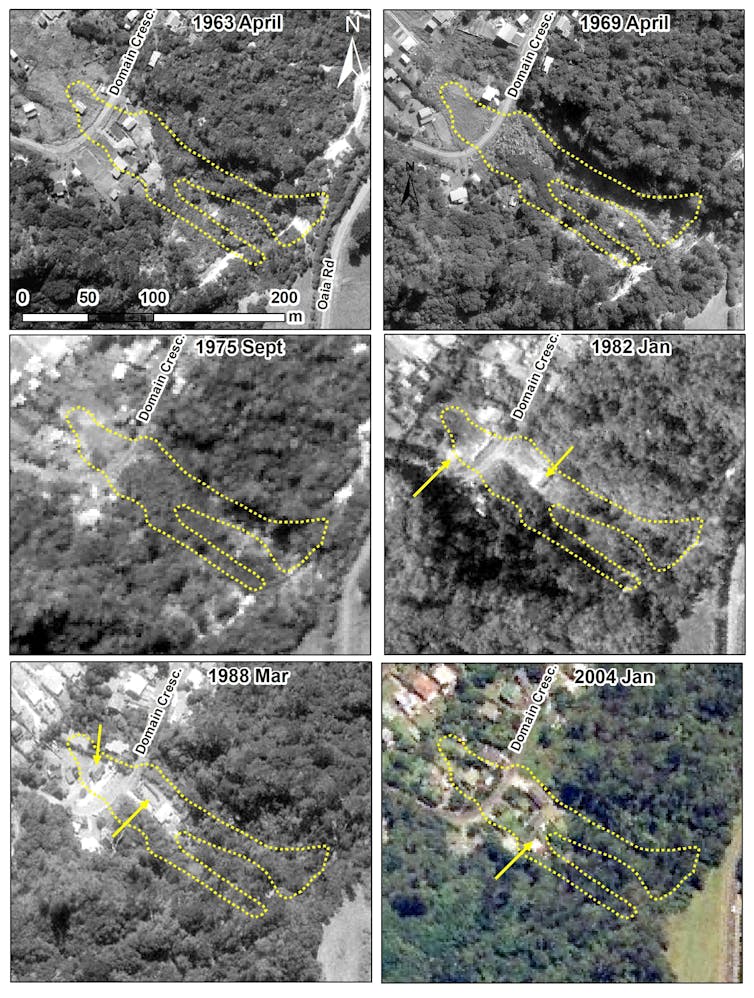

A 1966 New Zealand Geographer article recorded that witnesses said the landslide moved at 90 kilometres per hour. Soon after, it was reported a Rodney District Council engineer had stated no new houses would be built on the 1965 landslide footprint. This held until the early 1980s, when gradual house construction began again.

The timing of this new construction (denoted by the yellow arrows in the figure below) is intriguing. In 1981, the Local Government Amendment Act (section 641A) allowed councils to issue building permits for houses on unstable land prone to erosion, subsidence, slippage or inundation. Councils were also absolved of any civil liability.

Concern about the effects of section 641A was highlighted in 1986 by highly respected engineers Nick Rogers and Don Taylor in a paper published in New Zealand Engineering magazine, titled “Safe as houses”. While the Building Act 1991 and 2004 have improved matters, we are still dealing with section 641A’s legacy.

The Earthquake Commission (EQC) Act in 1993 was an important step forward for natural disaster insurance. But it stipulated that compensation can be refused if a house was constructed on unstable land.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the Rodney District (which includes Muriwai) was ranked first nationally in having EQC claims rejected on the basis that houses had been built on existing unstable ground. The then EQC chief executive, David Middleton ONZM, appeared on the TV show Fair Go explaining this.

Real and moral hazards

No amount of geotechnical expertise or planning control can produce absolutely zero risk. But communities should be able to assume potential hazards are identified and they are not exposed to them.

Geomorphological mapping of landforms using high-resolution LiDAR DEMs can prove useful in planning and decision-making, as well as landslide susceptibility mapping. This is where a range of parameters – slope angle, soil type, thickness, rock type, vegetation cover and land use – are layered on top of the DEM, within a geographical information system.

The parameters are statistically modelled and a landslide susceptibility map is produced. In many parts of New Zealand, this map will probably not bring news some homeowners and land developers want to hear.

But such a map can be useful for hazard zoning. As the tragic events in Muriwai have shown over the years, the set-back of buildings below slopes is sometimes just as important as set-back from cliff edges at the top of slopes.

Other mitigation strategies include real-time monitoring of risk either in-situ or by satellite. Ultimately, costly slope engineering can be a solution.

However, as Rogers and Taylor wrote in 1986, property owners are often willing to accept risk until the hazard eventuates. In other cases, a “moral hazard” exists where there aren’t incentives to guard against risk because of protection from its consequences by insurance or EQC coverage.

Unfortunately, this risk can also tragically extend to third parties. Whether such risk-taking behaviour continues after the Auckland floods and Cyclone Gabrielle remains to be seen.

But understanding landscape geomorphology and using it as the basis for more resilient planning so we can truly build back better, or undertake managed retreat, is now imperative

Martin Brook is associate professor of applied geology at the University of Auckland.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.