Professor Michael Milford and his colleague Juxi Leitner assess the scientific plausibilities of Thor: Ragnarok and finds them difficult but not always impossible.

Thor: Ragnarok is the latest Marvel movie out today that sees Chris Hemsworth back as Thor, but he’s not on friendly home turf. Instead he finds himself imprisoned on the opposite side of the universe from his beloved Asgard, and out of his depth in a gladiatorial contest with the Incredible Hulk (Mark Ruffalo).

But Hulk isn’t his only problem. Ragnarok (the end of his homeland of Asgard) is looming and Thor has new villains to deal with, including the warlike Hela, played by Cate Blanchett.

Other new characters include the eccentric Grandmaster (Jeff Goldblum), the fallen warrior Valkyrie (Tessa Thompson), the conflicted Asgardian Skurge (Karl Urban) and the hilarious Korg (played in motion capture by the director Taika Waititi himself).

Given the light-hearted tone of the movie, we’re going to have some fun looking at the “science” of Thor: Ragnarok.

We’ll take it as a given that there are superheroes with magical capabilities, and look instead at the numbers behind some of the characters and events. As usual, there are some minor spoilers ahead.

How do Hulk’s pants stay on?

Hulk is infamous for his pants staying on through his transformations, both from Bruce Banner to Hulk and back again. Given that these are normal pants, is this possible?

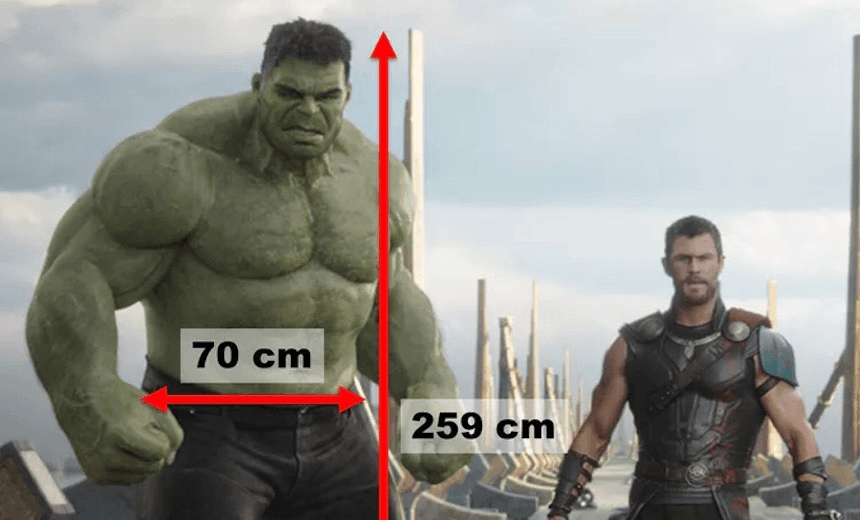

First we can calculate how much they need to stretch. In the movie, Hulk is about 259cm (8ft 6ins) tall and very solidly built, as explained by VFX supervisor Jake Morrison. Banner, according to some sources, is about 178cm (5ft 10ins) tall, and actor Mark Ruffalo says he’s around 175cm. He has similar stature to me (Michael) and my waist measures about 40cm across at the front.

So in transitioning from Banner to Hulk, his height goes up by a factor of 1.46, while his waist circumference goes up by about 1.75 times – more than his height because in Hulk form he’s more bulky.

So his pants would need to stretch by about 75%.

Finding stretchiness factors for jeans is challenging. Fashion websites quote figures up to 4% for stretch jeans. A scientific study found “stretchability” of up to 34% (after a few washes). So conventional jeans are probably out.

Pure spandex pants, on the other hand, are viable – they can stretch by more than 100% and then return to their original size. So if Banner is willing to accept certain fashion choices, he can maintain decency while morphing both ways.

Verdict: It’s stretching science a bit, but plausible.

Calling Mjölnir

Thor’s hammer, also known as Mjölnir, has an unpleasant run-in with Hela in the movie. With some abuse of physics, we can examine how Thor might be able to call his hammer back at high speed.

If Thor is using and abusing normal physics, he might call the hammer back by playing with masses. The hammer looks to accelerate back to Thor faster than normal Earth gravity (9.81m/s2) would make it fall – so let’s say it accelerates back twice as fast – about 20m/s2 – and he calls it back from 100 metres away.

There are at least two possibilities here: Thor increases his mass magically in a way that only affects the hammer, or the hammer increases its mass in a way that only interacts with a (magically unmoveable) Thor.

Either way, one of them has to temporarily have a much greater mass:

acceleration = gravitational constant × mass of large body / distance2

mass of large body = acceleration × distance2 / gravitational constant

= ( 20 × 1002 ) / ( 6.673 × 10-11 )

= 3 × 1015kg (or 3,000,000,000,000,000kg)

This is quite close to the weight of the Mediterranean sea (but concentrated in one extremely dense superhero) – so there would definitely have to be some way for the increased mass to only gravitationally affect Thor and the hammer – otherwise the environment around them would get ripped to shreds as well.

Verdict: Real-world physics takes a bit of a hammering.

Thor versus Hulk: Who would win in a fight?

The movie addresses this controversial and much-debated question in one way. Fans have disagreed on it forever. They draw upon reference material from the comics and movies, and arguments around Thor being a deity and Hulk being capable of near-infinite strength based on his rage.

What we can look at is what sort of strength it would take for Thor to throw the much bigger Hulk around in a gladiatorial fight.

Hulk probably has a specific weight. We can calculate it by scaling up the weight of a bulky human bodybuilder to Hulk’s height. Weight will scale up with the cube law.

One of the biggest bodybuilders in the world right now is Mamdouh Elssbiay, who is 178cm tall and weighs in at about 144kg in the offseason. We can scale his weight up:

Hulk weight = bodybuilder weight × height ratio3

= 144 × (259 / 178)3

= 444kg

This weight is in the range that Marvel provides of 408-635kg for Hulk.

Thor seems to knock him straight through the air about 50 metres along a fairly flat trajectory, let’s say accelerating him up to a speed of 300km/h (83.33m/s).

Assuming perfect energy transfer (in reality there would be loss), Thor would have imparted the following energy to Hulk:

Hulk kinetic energy = 0.5 × mass × v2

= 0.5 × 444 × 83.332

= 1,540,000 joules

The energy in a human punch depends on the sport, the intention of the punch, and the size and training level of the human, but it appears to be in the range of a few hundred joules.

So Thor’s punches would have to impart about 10,000 times more energy than a human punch to toss Hulk around like he does.

From a momentum perspective, for Thor to not shoot backwards when he punches Hulk, he would either have to temporarily have a great mass or have some other magical power that defies conservation of momentum laws.

Verdict: Lucky Thor’s a god.

Super superheroes or wretched Ragnarok?

Thor: Ragnarok is a fantastically funny movie, the best in the Thor series, and one that finally addresses some unanswered questions that comic fans have long debated.

The movie mixes elements that stay somewhat true to real-world physics (Hulk’s weight) and others that require blatant violations of them (Thor’s hammer; fighting).

Most importantly, we have calculated that it’s plausible for Hulk’s pants to stay on, maintaining decency through Banner to Hulk transitions and back again.

Michael Milford is a professor at Queensland University of Technology and Juxi Leitner is a research fellow in Robotics & AI at Queensland University of Technology

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The Spinoff’s science content is made possible thanks to the support of The MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology, a national institute devoted to scientific research.