A petition to include ‘Aotearoa’ in New Zealand’s name attracted more than 6,000 signatures and has now been presented to parliament. Lewis Holden from Change the NZ Flag explains why he’s backing the idea.

Before I go any further, yes it’s me, the change the flag and change the head of state guy, at it again, tilting at another colonial windmill. And yes, this is something else I think we ought to look at as a country: what we actually call ourselves.

Only this time, it’s not me pushing the barrow. It’s a guy by the name of Danny Tahau Jobe, who created a petition on parliament’s website for a “Referendum to include Aotearoa in the official name of New Zealand”. That is, call ourselves officially ‘Aotearoa New Zealand’. Jobe’s petition attracted over 6,000 signatures and has been picked up by Greens co-leader Marama Davidson and Labour’s Louisa Wall. The petition was presented to parliament by Davidson on May 1 and duly referred to the relevant Select Committee (Governance and Administration) by the house. Submissions will be opening shortly.

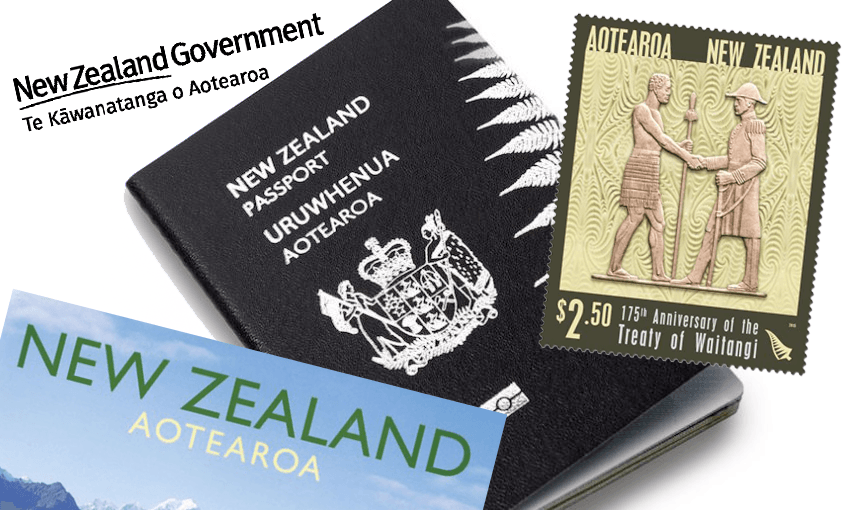

Jobe’s reasoning for the change is simple: we are now in a situation where official documents of national identity, birth and citizenship certificates, passports and money have ‘Aotearoa’ and ‘New Zealand’ together as the names of the country. Only New Zealand has official legal status. Both names together will officially confirm and enhance our nationhood and uniqueness in the world. Jobe adds “Aotearoa New Zealand, it’s not just the name, it’s our language, our culture, our identity and history.”

That’s what the core of the debate on this issue will be. What is our culture or our identity and history? These are the perennial questions when it comes to our flag, head of state and name. Since te reo Māori was declared an official language of New Zealand in 1987, the use of Aotearoa as the te reo equivalent to New Zealand has proliferated, and as Jobe’s has noted, it is now part of a lot of our official documents. So much so that Aotearoa now has the ire of those pining for the good old days when Māori were in the background of New Zealand society – you know, the “best race relations in the world” times.

As an aside, I remember a few years ago having such an argument with none other than John Ansell during the flag debate. He complained bitterly that no one had ever been asked, democratically, whether Aotearoa could be used alongside New Zealand. I pointed out to John that there was no vote taken in 1645 when Dutch cartographers named our islands after the Dutch province of Zeeland.

Of course, the name in use at that time was Te Whenua o Aotearoa, the land of the long white cloud, going back to the first migrations. Let’s be honest, the name’s a heck of a lot more poetic than ‘hey this place looks like it’s shaped like our southern province!’ Despite the transliteration of Nu Tireni (for New Zealand) being used in both He Whakaputanga (the Declaration of Independence) in 1835 and Te Tiriti o Waitangi in 1840, Aotearoa still dominates. For example, Aotearoa was used in the 1878 translation of ‘God Defend New Zealand’, although it’s only since the 1990s that both English and te reo versions of the national anthem have been sung together.

Does the change have to be by referendum? Arguably, no. Now I’m sure many people will find it surprising that I’m now saying this, but my thinking when it comes to referendums is that they’re too much of a blunt instrument. The flag debate demonstrated this brilliantly. According to UMR’s polling right at the end of the flag referendum process, support for the new flag was 35% and current flag 65%. However, when they asked those who said they supported the current flag whether they’d like to change the flag but not to the alternative offered, UMR found 29% agreed. In other words, the total support for change was about 54%, subject to getting the design right. And so, the referendum was lost.

When it comes to the name change, the solution is simple. Our country’s name is defined in the obscure Interpretation Act 1999, the go-to statute for legal pedants and insomniacs. The Act defines New Zealand as the part of the “Realm of New Zealand” that isn’t the Ross Dependency, Niue, Tokelau or the Cook Islands. The Realm of New Zealand is all the territories where the Queen is head of state. Confusing? Yes, it is. But luckily this definition means we can easily amend the law so that ‘Aotearoa’, ‘Aotearoa New Zealand’ or similar are also the parts of the Realm of New Zealand that aren’t the main islands of New Zealand.

So we don’t need another $10 million on a referendum. After all, we’re already using Aotearoa and Aotearoa New Zealand anyway. Those who take issue with the name really don’t have much of a case against change other than potentially cost. But again, that’s already largely been absorbed. Let’s just make it official.